The Murder-Filled History Of The, Uh, Fancy Hat Industry

Modern conservation laws prevent you from shooting an endangered condor because it looked at you funny, dumping nuclear waste into a bear den in an attempt to create super bears, and otherwise living like a Captain Planet villain. You probably know this wasn't always the case, with America's attitude having once been "Gunning down hundreds of buffalo from a train is conserving our fun."

But what led to improvements? Better science? The invention of Big Buck Hunter arcade machines? Well, yes, but also murder. And so, because we need a break from our depressing research into ursine tumors, here is the story of Guy Bradley.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, gigantic feathered hats were all the rage. Nothing made a woman more attractive than looking like she was in the early stages of transitioning Animorphs-style into a peacock. An ounce of feathers was often worth as much as an ounce of gold, and a hell of a lot of ounces were being harvested. In 1902, a single London auction unloaded 48,240 ounces of heron plumes, which necessitated about 192,650 dead herons. Worldwide, millions of birds were being slaughtered each year to fuel Big Fancy Hat. (Add this to the rash of early 1900s egg crimes and it becomes rapidly apparent your great-great-grandparents reeeally hated anything that dared to evolve wings.)

Don't Miss

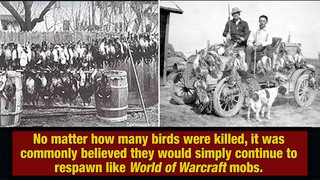

Nature's bounty was once considered inexhaustible. No matter how many birds were killed, it was commonly believed they would simply continue to respawn like World of Warcraft mobs. Nowadays, of course, we know that denying humanity's impact on the environment is a fringe stance held only by prominent politicians, business tycoons, and influential YouTubers, but this ignorance drove numerous species to the precipice of extinction and wiped out the passenger pigeon entirely.

Bird enthusiasts began to question the whole "leaving carcasses to rot in front of their starving offspring en masse is totes fine for the environment" argument, and groups formed to encourage protective legislation. These included early chapters of the Audubon Society whose members, completely unaware that comedy publications would be snickering at them over a century later, signed a pledge promising to never "molest birds." The Society that you now associate with laidback grandmas was promptly declared "extremist" by politicians and hat lobbyists, as their "self-righteous" concern for the environment would supposedly ruin the careers of hardworking Americans. If that reminds you of the current climate change argument, that's because time is a flat circle that mocks you for caring about things.

But in 1900 conservationists -- backed by their own political supporters, like New York Governor Teddy Roosevelt -- succeeded in passing the Lacey Act. As America's first federal wildlife law it ostensibly cracked down on indiscriminate bird slaughter and the interstate traffic of the feathers plucked from their corpses, but it was often enforced about as well as jaywalking laws. A 1901 Florida law that protected plume birds was equally toothless. And that's where Florida man Guy Bradley comes in.

A teenage Bradley guided hunters through the Everglades as they killed thousands of birds and, as a young man, he would hunt birds himself for extra cash. But he respected the Lacey Act and retired from plume hunting -- not an easy decision when a few days work could make you more money than other jobs in the region paid all year. Luckily for him, in 1902 the new father was soon offered the job of Florida's first game warden.

Bradley was recruited under the Hollywood thriller logic that he knew all the tricks poachers would use. Most hunters respected the new laws, and the reasoning that their good times couldn't last if Florida's birds were annihilated. Others would quit after Bradley caught them but let them off with an educational lecture. But some just saw fewer competitors as an opportunity, which left Bradley and a couple deputies with hundreds of miles of Florida wilderness to cover.

Bradley's patrols were serious business: he was threatened a few times and even had a couple shots fired his way. Bradley had his own gun and a reputation as a sharpshooter and, while most of his fines and arrests were peaceful, he was prepared to have a gunfight that would make Michael Mann proud should one be needed to save an egret. When there wasn't violence, there was espionage: hunters would sometimes shadow Bradley and then wipe out a rookery once he carried on with his patrol, while Bradley set up a spy ring to inform him of suspicious activity. There were setbacks, but bird populations were recovering. Then, in July 1905, he had an encounter with Walter Smith.

Smith was a Confederate veteran who had been encouraged to move to Florida by, of all people, Bradley's father. The two families had been friendly, but their relationship was ruined after Bradley arrested Smith once and his eldest son twice. Smith was also feuding with his neighbor, and believed Bradley was on their side. Oh, and earlier in 1905, Smith's house had been riddled with gunfire while his family was eating dinner, forcing them to hit the deck and pray for their lives.

This trot-by was presumably related to his neighborly feud but, regardless of the cause, a crotchety old man with multiple ongoing disputes and a legitimate reason to be paranoid is not the most enviable target for law enforcement. Smith had flat-out threatened to murder Bradley if Bradley touched one of his sons again, and then they provoked Bradley by poaching within earshot of his home. Bradley went out to confront them, and he never came back.

Smith turned himself in for killing Bradley, and the ensuing trial was predicted to be perfunctory. But Smith's political connections, alongside a stacked jury sympathetic to poaching, made it an ugly affair. Smith claimed self-defense, while Bradley's supporters argued that if Bradley had fired first Smith would have too many holes in his head to testify. Smith's death threat and evidence that Bradley's gun hadn't been fired were ignored and so, after five months in jail, Smith was declared a free man. He returned to a home that had been burned down by two of Bradley's brothers-in-law.

While conservationists were outraged, "You'll probably get murdered by a criminal who walks free" didn't look good on recruitment posters, and Bradley was never replaced. Hopes for a propaganda victory in the media never materialized either, as milliners ignored the Bradley murder while pivoting to the totally credible argument that all of their feathers were now just being found on the ground. And so the Everglades became a shooting gallery again.

In 1908, a warden who worked elsewhere in Florida, Columbus McLeod, vanished, leaving behind evidence that he had been murdered with an axe. Later that year, South Carolina warden Pressley Reeves was shot dead in an ambush. No perpetrators were ever found but, aside from proving that every game warden had a name that said they brushed their teeth with a whiskey-soaked knife, public anger could no longer be ignored. The Audubon Society, rather than forming a paramilitary wing, switched tactics to targeting hatmakers and thereby rendering poaching profitless.

The murders had cost the industry much of its political cachet, and in 1910 New York -- the centre of the fancy hat industry -- banned feather imports, the first of many new laws. Feathers could be smuggled in, but fashion trends were starting to change too. Hollywood was popularising a bob cut that clashed with hats the size of a shed, cars with a fancy new feature called a "roof" also made the size of plumed hats impractical, World War I encouraged thriftiness, and people were generally growing less enthusiastic about spending piles of money on ostentatious hats made through a supply chain that featured the murder of law enforcement. The industry struggled until the Great Depression dealt the killing blow.

While far from Florida's only hard-working activist, Bradley's dramatic death is sadly believed to have done more for conservation efforts than decades of quiet service would have. Piles of awards and locations are named for him, and his life was the basis of a 1958 movie. While he helped pull several bird species back from the brink of extinction, Everglades bird populations are still only about 10% of what they were in their heyday, and broader ongoing efforts to preserve the Everglades are stuck in their own swampy quagmire. So if Bradley could take a literal bullet for the environment, we can all, like, only order from Amazon once a week instead of three times.

Mark is on Twitter and wrote a book.

Top Image: Dori/Wikimedia Commons