Ben Schwartz on His Love of Improv, Playing Sonic and Almost Missing Out on Jean-Ralphio

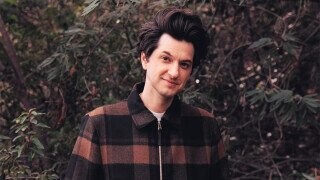

Ben Schwartz is asking me about myself. He’s just talked at length about his early struggles as a comedian, how he worked like a dog performing and writing anywhere he could just to establish himself, when suddenly he tries to shift the focus. “And now, here we are, and I’m talking to you,” he says, “wondering what books you have on your bookshelf.” Our interview is taking place over Zoom, him relaxing in his Los Angeles office, and he encourages me to show him my recently installed built-in bookcases that are behind me. It’s something I’ve noticed he’s done in other interviews — asking the interviewer questions so that the whole conversation isn’t about him — and Schwartz admits it’s just his personality.

“I’m very inquisitive — I don’t need to talk about myself,” he tells me. “If you tell me anything about your life, I’m like, ‘All right, he just built those (shelves), and he’s starting to put it up. If he had a choice to put anything he wanted, what’s up there? Why did he build those shelves in the first place?’ I like learning about humans.”

This curiosity has served the 41-year-old actor and writer well, in two ways. For one thing, over our hour-long talk, he comes across as sweet and unassuming, someone who’s much happier lauding praise on other people than himself. But also, that openness has undoubtedly served his great love, which is improv.

Don't Miss

Schwartz has several projects out this spring, the biggest of all being Renfield, in which he appears opposite Nicolas Cage, who’s playing Dracula. He’s the star of the Sonic the Hedgehog films and has been part of the ensembles of The Afterparty, Space Force and House of Lies. He’s a published author and an Emmy-winner. He does so much voice work that it’s hard to keep track of all the shows he’s on. And his recurring role as Jean-Ralphio Saperstein on Parks and Recreation made him a beloved figure on that beloved sitcom. But with all that on his résumé, he has never lost his passion for improv, which first got him excited about comedy decades ago and which he still does on a regular basis. In fact, when we talk, he’s busting to share news that hasn’t yet been made public: In September, his long-running improv show Ben Schwartz & Friends will be coming to Radio City Music Hall, easily the biggest venue he’s ever performed in.

“I’m so excited, dude,” he says. “I can’t wait.”

Lots of things make Schwartz excited. He’s quick to praise collaborators for being amazing, incredible or kind. He’s an enthusiastic cheerleader for the projects he’s part of, insisting that he doesn’t sign up for anything if he’s not 100 percent sure it’ll be fun. “I don’t lock myself into something that I wouldn’t enjoy,” he says. “I don’t want to do that to the project, and I don’t want to do it to me.” Tellingly, when I broached the subject of Thomas Middleditch, his former improv partner accused of sexual misconduct, Schwartz pivots away from those darker matters. Clearly, he wants to stay positive.

Which isn’t to say he’s afraid of discussing weightier subjects like failure and anxiety. Like any good improv performer, he engages fully in the lively back and forth between two people, wondering what might come out of it. Schwartz may not need to talk about himself, but when he does, you learn a lot: about his parents, about the dreams he had as a kid, what it was like to write the opening for the Oscars and why he doesn’t dwell on the applause he gets on stage. And he’s more than happy to discuss playing Jean-Ralphio — and how he almost lost out on the chance because of a miscommunication.

You have a bunch of projects coming out at the same time: the animated We Lost Our Human; the Kevin Hart action-comedy Die Hart 2: Die Harter; and then Nicolas Cage’s Dracula horror-comedy Renfield, where you’re playing the bad guy. We’re getting to see all these different sides of you.

All my stuff seems to always want to come out in a month span. Last time, it was Sonic 2 and Afterparty and Space Force all in the same month. But you’re right: One is my voiceover work, Die Hart 2 is close to sketch comedy what we’re doing over there — it’s kind of bananas, it’s great — and then Renfield is straight-up action sequences and fight scenes and tattoos and guns, big budget, really fun.

Obviously, you don’t control when these things come out. But when you sign up for projects, are you consciously thinking, “I want to do a little bit of A, and then a little bit of B, and then a little bit of C”?

I just keep saying yes to things that make me excited. The hope is that I can keep doing that. The way that I started — I mean, the way that any of us started, we want to find a way into this industry — I did everything. I was a freelance writer for Letterman, freelance writer for Weekend Update. I was performing at Upright Citizens Brigade. I was doing improv. I tried stand-up at the beginning. I was freelancing articles for Wizard magazine or anybody that let me. I was a staff writer for Robot Chicken. I wrote three books that are postcard books — like, anything I could do. And that kind of work ethic hasn’t left me — I’m always trying to keep things in the fire.

The intention is always to do stuff that I find interesting, and then always try to reach for those really cool (projects). Renfield to me is a really cool little thing — I never get to play the guy with slicked-back hair and threatening someone, because it couldn’t be less of who I am as a human being. But it’s ingrained in me from the beginning just to hustle and try my hardest to get anybody to pay attention and hopefully hire me for anything.

Does that come from your parents? A lot of people who start out wanting to be in the arts have to prove to their mom and dad, “Look, I can make a living at this.” And being busy is a way of showing them that this career is viable.

My parents are from the South Bronx. My parents had no money growing up, and they worked their butt off to get us to a place where we had enough money to do fun things. My mom is a music teacher in the Bronx for 50 years, and then my dad worked different jobs with the YMHA and then directed the whole YMHA, and then was in social services and then worked in real estate. I just watched him work his ass off — and then my sister when she was able to work. The first time I worked, it was illegal, because I didn’t have my working papers yet — I had to lie about how old I was to get the job. It’s just a part of what my family does. It’s ingrained in me that that’s what we do: We get out there, and we work for what we want.

When I got out of college, I told my parents, “I really want to try to do comedy.” And my parents were like, “All right, try it for a year or two, and if it doesn’t work out, then get a real job.” And so, in my head, I was like, “I’m going all-in on this, and I’m pushing as hard as I can.” And I was lucky enough where my parents helped me out with rent for the first six or seven months, and then I was able to slowly pay my own rent. But, yeah, it was a matter of “I really want to do this. Can I imagine how lucky I would be — and how happy I would be — if my job is to make people laugh? That would be incredible.”

At the beginning, I never slept. I woke up at 6 a.m., I wrote jokes for Letterman. I then was a page at Letterman to make enough money. And then I was an intern at UCB, so I got free classes at UCB, and then I was a bartender at UCB so I could make a little bit more money, and I’m always performing anywhere I can perform. It was just a part of that hustle — “All right, I got two years to try to figure this out” — and then slowly being able to support myself and then slowly starting to establish myself a little bit more and a little bit more.

One of your first big successes after moving from New York to L.A. was winning an Emmy for writing for the 2009 Oscars, the one Hugh Jackman hosted.

When I got the Emmy, I was living in a really tiny apartment in Los Angeles. It didn’t feel safe to put it out in the open, because people could see it. So I put it in my kitchen — which was basically my living room — in a closet, and as a bit, I would put crackers in the globe. (Laughs) Then I found out that that rusts the Emmy, so I have all these rust marks all over my Emmy. But now it’s in my office.

I’m so curious what the process is for coming up with jokes for the Oscars.

We basically wrote Hugh Jackman’s opening number — that was what we were hired for. I also wrote a bunch of (other) jokes, but they had a full team writing that stuff, so (the producers) were like, “You guys deal with (the opening number),” which was great, because it was me, Dan Harmon, Rob Schrab, and we got to go bananas. That opening, it’s pretty out there and pretty fun

It was a great opening because it was so lo-fi and charming.

The whole idea, all of us came in with the same (thought): “All right, it’s the recession. How do you do a musical opening number during the recession?” And then we all watched all the DVDs, and none of us watched The Reader, so there’s a song in that opening number that’s like, “I have to watch The Reader,” which was very fun. (laughs)

It was basically the three of us in a room. Dan Harmon is a genius. Rob Schrab is a genius, too, and he’s so creative, and he built all those things (for the opening). It almost felt like we were doing a school play. But, also, we were writing in the Mandarin Oriental — I’ve never been to a fancier hotel in my life, so it was such a weird thing to us being little comedy nerds. (Laughs) This is before Community came out, so those guys hadn’t really blown up like they have now. It was great.

When Jackman actually did the opening number, where were you?

We were at the show — we were in a room in the back. We had a tiny little TV, and the three of us were huddling around it. It was so exciting to see people laugh at our stuff — at the end, he got a standing ovation, and we were going crazy. It was 2009 — it was 14 years ago. I invited my best friend — he came in from New York — and because I was backstage, he sat by himself at the Oscars. He was like, “I just passed Meryl Streep!” I was like, “That’s amazing!” It was a very surreal, crazy moment, especially because I’d been in L.A. for a very little time.

Did you think that opening was going to kill?

I thought it was pretty funny.

But that’s a really tough room.

Oh, impossible room. We knew that there’s a chance that it could bomb, but you watched (Jackman), and he’s so good and he commits so hard and he’s so charismatic that you’re like, “He’s going to crush it.” And then it’s a matter of if people are on board from the beginning or they’re not — and they were immediately on board. I’m so impressed how comfortable he is in front of all the most important people in Hollywood. That was a really fun day.

It was really funny to go from that to… At that time, I was sleeping in a tent in my friend’s living room, because I didn’t have a place yet. I would go from the Oscars to literally sleeping in a tent. Just like, “Oh, right: This is where I am really right now. I’m the person that sleeps in a tent on someone’s floor. I’m not quite at the Oscars yet.”

In recent years, you’re probably best known for voicing Sonic. In interviews, you’ve said you based his character on thinking of him as a big, excited kid. Was that the kind of kid you were?

I was a very happy kid. I loved to make people laugh. But I think with him, it’s more like, he’s so excited about everything, because he’s been doing everything by himself for so long and all he wants is to have a friend to talk to — he has all this energy that he lets out through running and also talking. The way that I played that character is like, “I’m talking fast, I’m so excited, I can barely get the words out of my mouth!”

As a kid, I was probably not that excited, although chocolate made me hyper — I remember that. Anytime I’d have chocolate, I’d be running around the room. But I always want to make people laugh, and I always loved people — if I met somebody, I’m meeting them excited to be like, “Hey, how are you?” Same with today. I was an anthropology major, psychology major — I love human beings and learning about different cultures and how they do things, and so that openness is there. But (Sonic’s) absolute energy — and probably sometimes a little bit annoying — I don’t know if that was totally me. But I was definitely a happy kid.

How does studying anthropology and psychology help with comedy?

There’s some people who went to theater camp — they’re amazing, incredible actors, and they see the craft in a beautiful way — but I really like the idea that I didn’t come into performing till my last year of college. My studies were never that — it was just like the last year and a half where I started doing improv and took an acting class at school. I really like the idea that I come at it from there, because I feel like I got all this knowledge about all this other stuff that I can put into my acting.

Anthropology, it’s great — it’s this curiosity of human beings. And there’s a lot of empathy in anthropology, if you’re doing it the right way. And psychology, I mean, to understand why therapy is important and to break down how we use our brains and how we try to fix our anxieties — I find it to be amazing. It helps you with patience.

The way that I did college is, basically, I found the things that made me interested and I found the teachers that I found interesting, and I just kept taking classes with them, because then it didn’t feel like I was going to school. We did sports in anthropology, and then I did abnormal psychology — I loved the whole spectrum of it. It never felt boring to me.

You’ve done improv for a very long time. What do first-timers get wrong? What incorrect assumptions do they have that they need to be disabused of?

First of all, there’s two different forms of improv. One is short form, which is like games — like Whose Line Is It Anyway?, which is absolutely improv and very funny, and I grew up watching it and thought it was hilarious — and then there’s something that Del Close helped create in Chicago that Amy (Poehler), Ian (Roberts), Matt (Besser) and Matt (Walsh) brought to New York, Upright Citizens Brigade, and that’s where I learned it.

The first thing I would say, if people are doing long-form improv, is they think they have to be funny quickly. It’s hard to get comfortable with not knowing what’s going to happen — it’s hard to get comfortable with “Oh my god, where is this going to go?” People make jokes and, oftentimes, when you make a joke, you’re getting in the way of a scene — you’re just looking out for yourself, but the whole idea is we’re trying to make everybody on stage look great. If I’m doing a scene with you, I’m trying to make you look fantastic — I’m trying to make the scene make sense, and I’m trying to allow it to evolve.

The other big thing that people do is they think there’s a lot of funny in “No.” If it’s like, “Oh my god, there’s so much snow outside,” and then you go, “No, there isn’t” — that’s funny for one second, but now there’s no scene. But if it’s like, “Oh my god, there’s so much snow outside.” “I know! My god, did you see the snowman?” — now all of a sudden, we’re building. “Yeah, it kind of looked at me weird. You saw it too, right?” Now we’re building this world where maybe snowmen are real. There’s so much room to grow if you say yes and you add to it. If you say no, you’re kind of shitting on that person’s idea and you’re not allowing something to blossom.

You’ve got to be patient in improv. The first two sentences aren’t going to be funny off the bat. But you’re going to slowly find what the game is.

I’m surprised people actually say no. I’ve never done improv before, and even I know the whole thing is based on “Yes, and…”

It’s almost like, if you’re playing basketball and you train — “Put your elbow in, shoot it like this, that’s the right form” — but then when you’re in a game, it’s so exciting and you go back to your old habits and whatever made your friends laugh. You’ve got to find a way to be comfortable in that moment.

How do you get over that discomfort?

It's really scary. When you start doing any type of comedy, (how) you understand if you’re doing well is through laughter, right? In drama, there’s nothing like that — if you’re doing a great play, I guess you could wait for people to (gasp). But our judge, our instant gratification, is laughter — we can find out immediately how something is going through laughter. So, of course, it’s going to be so scary when the first couple sentences, there’s no laughter. But, man, it’s just like anything. It’s like when I write movies: I can’t just have comedy, comedy, comedy, comedy. You’ve got to have dramatic beats, and then that comedy hits so much harder. You have to find those moments to balance drama and comedy.

But it absolutely took time to trust that we’ll get there. I remember taking classes and the teacher being like, “You’ll get there. Take your time. React truthfully — you’ll find these things.” That’s how UCB functions: Find the game in the scene. With that tool set, I can get on stage with any UCB person — but also, after a while, you can get on stage with almost any type of improv school. When I do Ben Schwartz & Friends, Ryan Gaul is in the Groundlings, and he plays there. And then I have some people that came from (Improv Olympic). It’s just basketball: If you know how to play basketball, you can play with anybody, even though your way of playing might be a little bit different than this person’s. I love that team-sport (mentality). And that’s an anthropology thing also: us doing it together.

Despite all the film and TV work you do, it seems like improv is something that remains pretty close to your heart.

Yeah, and there’s a fun show I’m going to be doing — I’ll be doing my biggest improv show ever. The venue had told us that I’m the first improviser to have a show there — I’ll play Radio City Music Hall in September. It’s so insane to me, because I’m from New York, and it’s 6,000 people. Up until recently, there was no touring of long-form improv. TJ and Dave did a couple things in New York and toured a little bit, and these big venues that Thomas (Middleditch) and I did and then Ben Schwartz & Friends did. But the fact that we’re going to play this 6,000-person venue...

I hope the show goes great, but even if it didn’t, I did it. We did it. We played Radio City Music Hall. And then Dave Kloc will make a poster about it — it’ll go on my wall, and every time I look at it, I’ll smile and be like, “We only used to perform for 90 people.” That’s what a sold-out audience at UCB was forever — 110 if you’re on the floor. I’m very, very excited. I’ve been doing improv since 2002, and (Radio City) is the pinnacle of all that hard work. Now I’m going to find out if it works for 6,000 people. I know it works for 3,600, but does it work for twice that? I have no idea.

Obviously, improv comes from scratch. But is there ever anything you’re thinking of before you go on stage? Something that maybe you want to bring to the show?

It’s so funny, because people will come to the show, know that it’s made up, watch the show, and then be like, “That wasn’t made up.” There’s nothing planned. We have absolutely nothing. I interview someone in the audience, and we improvise off of that for an entire hour-long show, and we never know what we’re going to do. It’s the same reason why it was so hard to sell the (Middleditch & Schwartz) specials: All these people are like, “All right, well, what is it?” I’m like, “Oh, we don’t know.” They go, “Yeah, but when (a comic) does stand-up, they tell us what the stand-up is about. What’s yours about?” And we’re like, “It could be anything. It literally could be anything. Who knows what it is?” It was very difficult to sell that.

That’s why I’m so impressed that so many people are showing up — they have no idea what they’re coming to see in terms of content. Sometimes people will know what improv is, and now more and more people know what long-form improv is. But this New York show is going to be awesome. I have no idea how it’s going to go. It’s such a big venue. I have no idea how it’s going to play, but it’s going to be so exciting. I’m going to learn so much about how much we can push this form crowd-wise.

So when you walk up there, your mind is just a complete blank?

A hundred percent blank. My friend calls it a meditative state, because I can only think about what’s happening in the moment. These shows are happening so quickly that you can’t think about anything other than what’s happening. But I’ll get on stage with nothing. I’ll look at the crowd, I’ll say hello. I’ll talk nonsense just at the beginning to warm them up, to make them feel comfortable — sometimes, when people come to these shows, they’re a little bit nervous: “What the fuck’s going to happen?” Then I invite our improvisers on stage. And then, where the show goes is totally up to the story of the audience.

You got to keep your mind as open as possible — really, what you’re doing is you’re inputting information. The second this person starts talking, I’m trying to remember everything I can: “Oh, that’ll be something that I could start a scene off of” or “I’m going to keep that in the back of my head.” They’ll talk about a character — “Yeah, my boss…” — and then I’m like, “Okay, if I can see a place where I can enter as this character, the audience will connect with it immediately.” You try to input, input, input — and then while you’re creating, your brain simultaneously is trying to see if you can call anything back. It takes a lot of training, but the goal is to live in the moment as much as we can.

Throughout your career, you’ve given interviews where the person points out that you seem to be working all the time. You still seem to be working all the time. I understand you like doing projects that excite you, but are you getting any better at saying no?

I just passed on something, and when you pass on something, oftentimes there’s a number attached to it: “You could get paid this much money if you did this.” And because I started off in this industry making no money, there’s still that piece of me (that remembers being a) beginner. Anytime I pass on something, I think, “Oh, man…”

But the older I get, the more I value personal time and finding that balance. I went really hard into work for the majority of my career, and now the past few years, I’ve really been trying to make sure that I have time for my family, people that I love. I’ve been getting better at saying no. I don’t have the absolute need to do everything. I have a little bit of money now, so I don’t have to say yes to everything. In the past, I had no choice: “I don’t care what I’m doing — if I don’t get this, I don’t eat.” That’s a whole different feeling than now that I’m 41. There is some power and some fun in that “No.” But because of how hard I worked, it’s like, “God, what if that ‘No’ was the last thing I’m ever going to get offered?!”

That anxiety never leaves. I don’t think it would — I think it’s kind of there. Anxiety pushes me to work really hard, but also torments me as well. I remember a therapist said once, “The way that your brain works in improv — the way that you can function very quickly — is fantastic, but also when it comes to anxiety, that stuff is going to work against you. That fast-moving thing is going to hit your brain the same way.” And I was like, “Oh my god, you’re right.” If I get anxious about something — like if I feel like I’ve offended somebody — I’ll be like, “Oh my goodness, should I call them? I should call them. I should probably call them, right? Oh my god, what if they’re thinking about it?!” It’s funny that my speed and creativity can be output in this fun improv way, but also can torment me in an anxious way on the other side.

Sonic isn’t the only animated project you’ve done: There’s also BoJack Horseman, Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, DuckTales. What’s the secret to being a good voice actor?

When you’re doing voiceover, your voice is going to inform the animator, so you’ve got to give them more information than what you would normally do if it’s just a performance on screen, (where) someone can look at your face and see you’re sad. You really got to sell it. When it’s time to be big, you be big — you try to inform what’s going on. If you ever videotape me recording, I am doing the things my character’s doing. If he’s running, I’m running. If he’s upset, I’m upset. And I think that’s big.

One of the things that people do if they first get into (voice acting) is they don’t act. It’s intimidating, because they don’t have a partner to act against. I ask the voiceover director (to) read the other person’s lines so I could always have something to play with. You really try to go for it. Sometimes, people swing and miss when they’re just saying the words, and they’re like, “I don’t know, what am I doing?” I think committing, really realizing, “Hey, if this is a silly scene, this is a silly scene — if this is a dramatic scene, this is a dramatic scene” — and not being afraid to go serious and then goofy (is the key). You’re outputting so much information to other people — to other artists to make your work better — so why not give them as much as you can?

I want to talk about your hair. I feel like your hair is such an extension of your demeanor: It’s big and buoyant and full of personality. Do you think about your hair as a part of your on-screen presence?

I moved from New York to Los Angeles, and I still was living in that tent and I just started renting a really small apartment. I didn’t have someone to cut my hair when I was here, but when I was in New York, my hair was always short, because I would either buzz it or I’d go to, like, Supercuts. I came here, and I probably had a writing job, but I didn’t have an acting job yet, so I started auditioning for pilots — and my hair started getting so big, and I just didn’t know where to go to get it cut. I was like, “All right, I’ll get it cut when I get a role.”

Then I got a callback for Mitch Hurwitz for a show — my first ever pilot, called Happiness Isn’t Everything. The show was me, Richard Dreyfuss, Jason Biggs, Mary Steenburgen — it would’ve changed my life, it was right after Arrested Development, it would’ve been enormous. When they told me I got a callback, Mitch called me, and I said, “I will cut my hair before this callback. I’m so sorry, dude, I just haven’t found…” He goes, “You will not cut your hair. It helps with the character. It makes that character even more unique.” And I was like, “Really? Okay, you got it — I won’t cut my hair.”

So, I did that, and then Jean-Ralphio was pretty soon after that, and my hair as Jean-Ralphio was so big — they loved it so much. Mitch is the reason why. My dad is very old-school: “If your hair’s getting a little shaggy, you cut it.” But I moved to L.A. where he wasn’t telling me that anymore, and it just grew so big. With Jean-Ralphio, people think I’m wearing a wig, but it’s always me — my hair was always that big. And, luckily, it hasn’t started falling out too much. It’s getting a little gray, but hopefully it’s good.

It blows my mind that you’re 41. You seem perpetually boyish.

When I started at UCB, me, Adam (Pally), and Gil (Ozeri) — the guys who did Hot Sauce together — we were part of the youngest people there. I was very young for Robot Chicken. I was just always “the young guy” for a while. And then, I don’t know what it was — something I shot in the past five years — someone (I met) was like, “Dude, I watched you when I was a kid.” And I was like, “Oh, fuck.” This actor that’s on the same thing as me is like, “You were such an inspiration to me coming up. You voiced Randy Cunningham. Parks and Rec, me and my mom would (watch that).” I was like, “‘Me and my mom’!?” It made me realize that I’m not the kid anymore. I was always one of the youngest people on all the shoots, and I’m no longer that anymore.

I’m fine with looking a little young-ish now, because I feel like I’ll look old for a long time. I’m not playing 20-year-olds anymore, but I can definitely play 30s still. I did play a dad once in a Disney movie, and they put gray in my hair before I had gray in my hair. My dad is very gray — I’ll be very gray. But, yeah, I still like that I can play younger things, because I think the comedy that I do lends itself to being younger rather than older. We’ll see how long I can keep this up — or see how long people want me to keep playing these roles. But, soon, it’ll be a lot of dad roles, I bet.

Because of the variety of things you do, I wondered if you started out as someone who thought in five-year plans.

I was still living with my parents when I was starting to do improv, and I said, “Okay, I’m going to pick three bucket-list things — three dream roles, three dream things. If any of these things happen, that will be amazing.” I was too embarrassed to tell anybody for a very long time, but one of them was to voice a character on The Simpsons. When I was a kid, (that show) was huge — and I got to do that. One was to be a guest on the Late Show With David Letterman, because my first job in the entertainment business was as a page for Letterman. For a year and a half, I’d help people to their seats, and I’d watch him, and I’d be like, “Man, how crazy would it be if I was on stage?” And I got to do that right before he got off. And then the third is to host SNL, which hasn’t happened, and maybe never happens. Those are the only crazy dreams I had.

I couldn’t even dream that I was Sonic. I couldn’t even dream that I would do a show with Steve Carell and John Malkovich — and the guys who did The Lego Movie (The Afterparty). I just never dreamt that I would get this far already — it wasn’t even on my kaleidoscope of craziness. I feel very, very lucky, because I know people that are funnier than me that have gotten less. I think it’s because I keep working so hard that at least I’m giving myself the opportunities to succeed — although you can’t be totally untalented.

But, yeah, there’s not really a plan. My things now are, I’ve sold a bunch of movies and TV shows — I’d love to get one on the air. I’m getting pretty close on one or two. So if you ask me now, what I’m thinking is, “I want this show that I’m writing for this awesome place to go. I want to be the lead of that show. I want to be in that room. I want to create all those moments.” This movie that I’m writing for me and Sam Rockwell for Searchlight, I want that to go — I’m on my third draft of it now, I’m going to finish it in the next two weeks. I want cameras to roll on my words. In the industry, people know that I write, but the world… people don’t get to see my stuff as much. That’s a big thing for me.

You’ve mentioned Thomas Middleditch a couple times. I loved those Netflix specials you two did. And like you said, it was hard to convince them to let you make those.

It was also scary because I did an improv special for Showtime called House of Lies Live, which was me and a bunch of people from House of Lies, but (this) was the only time I’ve ever seen myself improvise. The medium isn’t made in a way that’s supposed to be watched over and over again.

As you know, Middleditch was accused of sexual misconduct in 2021. Do you think the two of you would ever work again?

I know that, right now, I’m doing Ben Schwartz & Friends, and it’s been really good, and you can catch me in September at Radio City Music Hall, my man.

Understood. I’ll just say that I thought you two were a great team.

I love those specials. I’m so proud of those specials. I’m also so proud of how many times I’ve (done) Ben Schwartz & Friends shows where people will come up and be like, “That was the first time I saw long-form improv. I’m taking classes now. I’m so obsessed.” That’s the best. The fact that those specials were an “in” to this world, that makes me so happy. I still can’t believe we pulled it off — I still can’t believe they exist.

What’s interesting to me about improv is that, for the most part, it just disappears: You don’t have a record of all these shows you’ve done over the years.

There’s some shows that go so well that you’re like, “Oh my god, I wish I had (that).” I’m fine that all those things (aren’t recorded) — also, when you ask someone who’s never done improv before (to perform), it’s the perfect sell: “Hey, we do this, it disappears forever, there’s no recording of it, we’re just going to have fun.”

But there’s a piece of me now that’s like, “I wish I had some recordings, just to have.” That’s why I’m thinking about recording audio (for future shows), because that’s the easiest thing — when I go on tour, we wear these mics anyway, so I have everything set up. Someone just has to press the record button and play with the levels a little bit. I did love the idea that it disappears, and I still do, but why not have a backup of it, just in case? If it sucks, I have it — nobody will ever hear it. And if it’s great, maybe I’ll do something with it.

A lot of Hollywood posers talk a big game: “Oh, I’m working on this. I’m writing this.” But you’ve actually sold several projects — they just haven’t gotten made. How do you deal with that?

It’s hard — and at the beginning, it was really hard. You sell an idea to someone who says, “I love this idea so much, I’m going to pay you to write it.” And it’s like, “Oh my god, this is incredible,” and you’re writing this script, and then you’re getting their notes and you work your butt off and try to incorporate these notes, and you really put yourself out there. You’re really bringing a lot of your emotional stuff — some of the characters feel a little bit like you, and you’re bleeding a little bit into this — and then someone says, “No, we’re not going to make it.” All that work you did just...

I used to print (my scripts) out and put them on the shelf. But then I was like, “It’s not good for me to look at this cemetery of scripts.” (Laughs) I feel so lucky that I get paid for it, when I do get paid for it, but it hurts. I will say, there’s a couple things right now that I’ve worked so hard on and I believe in so much that, if they didn’t go, I’d be bummed.

I was just talking to someone about this: I auditioned for something, got very close to something very exciting, and I didn’t get it, and it hurt. And I was surprised — being 41 and doing this for 20 years — that me not getting roles still hurts. I was so embarrassed by that: I was like, “How is that possible? That’s insane.” But it still does. And same with my script. If this TV show that I’m writing doesn’t go, I’ll be really bummed out, because I think it’s special. You just put so much work into something for no one to see it. My live-action TV show hasn’t even been announced yet, so (if it doesn’t get made), no one will even know that I wrote it.

You have to find your self-worth through yourself because, man, it’s brutal out there. The way that I always think about it — and I think about it in a business way — (is) if they hire me to write something, it’s going to cost them not very much money, but if they want to say yes to making it, it’s going to cost them $50 million. So I understand the hesitancy to press the green light.

You just get used to it. It’s the same thing I tell people when they’re starting to perform: “You just got to get back out there and pitch another thing. You got to keep going. Our job is to be creative and create things and hope that they work out.” I always tell people when they take improv, “Take a risk, fail, learn from that mistake, and then get back out there. That’s how you find your voice. Failure is going to happen, especially at the beginning. And you have to learn from that failure, and you have to get better.” It’s the same way with writing: “All right, so this one didn’t work out. Well, let’s think of a different idea in a totally different world.” It’s a job. I feel really close about one of the things (that I’m writing). I really hope it works out, but if it doesn’t, it doesn’t — I’ll go onto the next thing.

You played Jean-Ralphio a long time ago now. Is it ever hard to still be so associated with that character?

Oh, no, I love talking about Parks. Parks was the best. Parks was one of my favorite experiences of my entire life. It felt like playtime, and everybody there was so kind — it was just great. Every season, (it) almost got canceled — now it’s regarded as this huge whatever, but I remember every single season, Mike Schur was like, “Well, we’ll see, I have no idea. They haven’t picked us up yet.” It’s just one of the best-written shows of all time and one of the best-acted shows.

You’ve said, when you got that part, that Jean-Ralphio was just a single-paragraph description.

Well, I actually met with them about a role that Louis C.K. got, which was Amy Poehler’s love interest. I just had a meeting — it was Harris Wittels, Katie Dippold and Mike Schur. Mike had seen me do these ESPN shorts that I helped create where I interview athletes, and he really liked it. He’s like, “Man, I feel like we can use you in here, but I think you’re a bit young for (the Louis C.K.) role. But with this show, Pawnee is like Springfield, and (new) characters are going to pop up — there’s a Milhouse, there’s a Comic Book Guy — so we’re going to have you in mind for things coming up.”

The craziest part of the story is they had Jean-Ralphio — they called my agent, and someone else was covering my agent’s desk, and they said, “Hey, we want to offer this role of Jean-Ralphio to Ben,” and that person passed on the role without even telling me! And then I got a call from Katie Dippold being like, “Hey, I thought we had such a good meeting, and I just wanted to ask why you passed.” And I said, “Passed on what?” She said, “Listen, I know it’s like a tiny little paragraph and it doesn’t look like much, but if it goes well, maybe there’ll be more.” I go, “What are you talking (about)? Whatever it is, I’m in. I don’t even know what it is, and I’m in.” She goes, “Someone passed for you.” I was like, “In a million years, why wouldn’t I want to do that?!”

So I showed up, I did one scene, it went great. Then after the first rehearsal, Mike Schur came up to me and says, “You’re going to be coming back,” and then he went upstairs and started writing Jean-Ralphio in the future scripts. There was always the hope that maybe there’d be more than one, but it was only one at the beginning. And (the initial description) was only one paragraph — it was me getting interviewed by Swanson.

That show changed my life. That’s still, to this day, probably the thing that people will recognize me the most from.

When you say it changed your life, what does that mean, exactly?

It changed my life because then when I went into a casting office, people could see my face and attach it to a role — they couldn’t quite do that before. And the good thing is, my character ended up being pretty funny, and people liked it: “Oh shit, he’s in Parks! He plays that crazy best-friend guy.” So now they can look at me, and they know who I am — as opposed to (before), they wouldn’t quite know where they remember me from, and they wouldn’t be able to figure it out.

All of a sudden now, I’m getting in the rooms a little bit more. I’m getting more auditions. I’m getting to the next level of auditions. And they know I can be funny. (Parks) was the first time that that type of thing happened — and once you start auditioning more, your confidence (goes) up a little bit. “Okay, I’m getting a little bit better in these audition rooms now. I’m getting a little bit better roles.” It’s harder for people to take big swings on casting someone they don’t know, but when they (know), “Oh, he’s from this,” they can sell it to the people that make those decisions. It was a big help.

You’re starring with Nicolas Cage in Renfield. Describe what Nicolas Cage is like.

I loved him. He was so committed to his character — he just came at it 110 percent. He was amazing, and he was kind. Does he have a pet crow? Yeah, I think he does have a pet crow! It’s everything you want Nic Cage to be. He dresses amazing. He has incredible stories.

We do press next week in New York, and I can’t wait to just hang out with him. I have so many questions. I mean, it’s almost a full-circle moment of talking about my anthropology background: I can’t wait to learn and just listen. Same with when I did a movie with Billy Crystal — I’ve been very, very close with him since. Anytime he goes into an old-school story or he’s talking about him and Robin (Williams), I am flying high, I am the happiest you can see me. I’m like, “I saw him in When Harry Met Sally…” Or Nic Cage or Malkovich — I got to talk to Jim Carrey about The Mask and Ace Ventura and Dumb and Dumber. Are you kidding me? This is insane that I have access to any of these people, because nobody in my life was in this field. It’s like being an astronaut — this isn’t real what I’m doing. It feels like it was impossible, and somehow I lucked out.

Dealing with rejection, dealing with Hollywood, you seem completely unjaded. How have you not gotten jaded?

Define jaded.

The complete opposite of how you carry yourself.

There are moments of cynicism. But I’m still thrilled. Listen, there’s a lot of failure in this, but there’s been so much success.

There are times when I’m not doing exactly what I want to be doing, and I’ll feel that — I’ll feel the anxiety. But I’m pretty good at centering myself. I’m a very humble, humble guy. Someone (asked) me once about what it’s like to be on stage in front of 3,000 people and get a standing ovation: In that moment, everybody’s clapping, and you’re the center of attention for a second, and you feel like you’re the most important thing in the universe. You have to realize that it’s just that moment in just that place. If you cut to me 60 minutes after a show, I’m in my hotel eating a cheeseburger (watching) ESPN or on Twitter. I’m by myself.

You have to be able to make sure that you understand what’s real life. That moment (when everybody’s clapping), I think people can get lost in that. People can get lost in Twitter just pressing the @ button and seeing what people are talking about them all day and just believing everything in there. It’s just so much easier to just be real and understand (performing) is very fun — but this is for this moment. If I go two blocks away from the venue, nobody will care that I just got a standing (ovation). Doesn’t matter.

I have parents. Everybody grounds me. Nobody treats me different than anybody else. It just seems like common sense. But I feel like there are people that need that feeling of feeling that important and that beloved at all times — I think that can get dangerous. I’m very happy that I’m able to see the whole span of things and to connect with the people I love instead of living in a fantasy world. I’m not that guy on stage getting a standing ovation every second of my day.