The Most Amazing Thing About Spider-Man (Is That He Even Exists)

After a long wait, Spider-Man: No Way Home is finally swinging into theaters. To celebrate, Cracked is doing a deep dive into the pop-culture web that our friendly neighborhood wall-crawler has spun for almost six decades.

We’re also giving away a year-long subscription to Marvel Unlimited. Learn more here, or add your email below to enter.

Don't Miss

It's a miracle that Spider-Man ever caught on—and not one of those boring miracles like childbirth or underdog hockey wins. We’re talking the full-on, holy shit kind of intervention that comes from a higher power. Because, truly, celestial-level meddling is the only thing that even sort of explains Spider-Man’s success, never mind the ways the character changed comicdom, and the world, for the next 60 years.

Introduced in 1962’s Amazing Fantasy #15, your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man was a hit right out of the gate, hailed as a hero of the tie-dyed counterculture. In the decades since, he’s become the flagship character of Marvel’s entertainment monolith, headlining dozens of comics, cartoons, and video games, starring in four different blockbuster film franchises, and spawning roughly 6,000 other successful spider-people, too.

And literally none of it ever should have happened.

A Brief History Of Mid-Century Periodical Publishing

Marvel

The 1950s were not kind to comic books, and especially not Atlas Comics, as Marvel was then known. Falling hard from the Nazi-punching highs of their previous previous incarnation, Timely Comics, Atlas spent the '50s trafficking in “derivative genre hackwork,” chasing whatever trends were popular, always barely hanging on (and barely not getting sued for plagiarism).

With the industry collapsing around him, writer and editor Stan “the Man” Lee started paying for artwork he didn’t need and hiding it in a closet, just to keep his friends employed—at least until publisher Martin Goodman found six months’ worth of drawings sitting around and fired all of Atlas’s artists. Lee, hoisted by his own petard, and pretty much all by himself now, was ordered to use up all that random art, coming up with dialogue and a story after the fact. That tactic would become the infamous Marvel Method that was, shortly, going to get him into a different kind of trouble. But first …

By the end of the '50s, after several ups and downs (and a year spent publishing nothing but reprints), Atlas had been reduced to releasing a measly eight titles a month of teen dramas, Westerns, and sci-fi shlock. That was all that was allowed by distributor Independent News, parent company of Atlas’s sworn blood-rival National Periodical Publications—or, as you might know them now, DC Comics.

But distribution, it turns out, wasn’t the only gift DC was in the mood to give. Thanks to its rebooting of the Flash and Green Lantern, America’s fascination with superheroes (and comics more generally) had been reignited. Add in a lawsuit from DC against artist Jack “King” Kirby, freshly broken-up with longtime partner Joe Simon and desperate for work, and things were, quite suddenly, looking up for ol’ Atlas Comics.

Fast-forward to 1961. Atlas—trying to distance itself from, well, itself—changed its name to Marvel and, finally, jumped onto the booming superhero bandwagon. By the end of the year, Kirby and Lee would come together to create the iconic Fantastic Four as a blatant attempt to mimic the success of DC’s Justice League of America.

Despite the name change, Martin Goodman was still the man in charge and still just reacting to whatever was popular. Justice League was hot, so, like Willy Wonka’s Veruca Salt, he pouted until he got one of his own. He didn’t actually give a crap about superheroes … or story, or art, or originality. And why would he? His nascent Marvel Comics was making good money selling anthology books full of giant monsters and Twilight Zone rip-offs.

The latter of which, by the way, is not an exaggeration. Here’s the final panel of “There Are Martians Among Us!” in Amazing Fantasy #15, published in 1962 …

Marvel

… which is totally not related to The Twilight Zone’s “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?” episode that first aired in 1961.

CBS

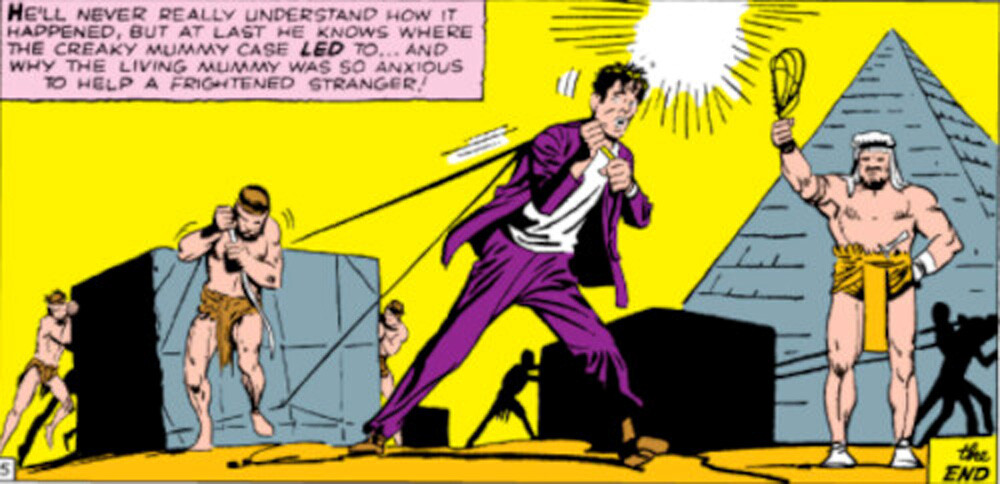

The absolute least popular of Marvel’s anthologies was Amazing Fantasy, on its third title in just over a year and filled with, well, filler—short, throwaway stories built entirely on O. Henry-like twist endings. In addition to the Rod Serling robbery above, issue #15 also included five-pagers about a bell-ringer saved from a volcano by God and a criminal tricked into ancient Egyptian slavery by a mummy.

Marvel

By the time the issue hit newsstands, Amazing Fantasy had already been cancelled by Goodman. Boss of the Year that he was, though, he’d neglected to tell the creative team any of this—hence all the in-comic text promising a brand-new direction for the book. Instead, Goodman just let Lee, Kirby, and Steve Ditko do whatever the hell kind of crazy bullshit they wanted.

And that, true believer, was how, in a second-tier publisher’s already-abandoned dumping ground for all the weird craptrash they couldn’t stick anywhere else, the amazing Spider-Man was born.

The Contentious Creation Of Everyone’s Favorite Wall-Crawler

The genesis of Spider-Man’s real-world origin, mired as it is in time, legends, contradictions, and living planet-sized egos, may never truly be known. But here’s our best guess.

Stan Lee, burnt out after having spent 20 years—his entire adult life—chasing after various comic book fads, wasn’t particularly thrilled about revisiting the same superhero tropes for a third time. (He and Goodman had already tried and failed to revive Namor, Captain America, and the Human Torch in the early '50s.) Instead, buoyed by the success of the bickering, cosmically-radiated family at the heart of Fantastic Four, he wanted to double-down on the “real world” aspects of spandex and superpowers with a hero who was, in the current parlance, messy AF.

Lee settled on making the character a teenager, then sat down with Jack Kirby to flesh out the idea. They came up, somehow, with a spider motif for the hero: Lee was either inspired by the Spider, a pulp hero, or he just liked the Hawkman name and riffed on that; or, maybe, Kirby was trying to cannibalize his and Joe Simon’s earlier creation, the Fly—it’s not like Kirby was known for not doing that—or, alternately, Lee himself was the one trying to ape Kirby and Simon’s Fly, either by accident or with malicious intent; or, possibly, they were both ripping off Fox Comics’ Spider Queen. Or maybe all of that, or some of it, or literally none of it, and a spider just chatted up Stan Lee on the subway and passively suggested someone should write a comic book about him.

However they got there, Kirby sketched out five unfinished pages for the character’s debut—which Lee absolutely hated. Kirby’s vision of Spider-Man involved a magic ring that turned the kid into a burly bodybuilder-type with a “web gun” on his hip. Aunt May was there, more or less, but the Uncle Ben figure was a crotchety, antagonistic military man, with, per Steve Ditko, big Thunderbolt Ross energy. Science only showed up as the theoretical hobby of a weird neighbor.

Kirby was kicked from the project (or left of his own accord) and Lee tossed the idea over to Ditko—with either a brand-new synopsis, only the original synopsis, all of Kirby’s sketches, or literally just the name “Spider-Man.” Ditko then came up with pretty much everything else, or he just drew what he was told to draw. Although, given Stan’s “add the dialogue and the specifics last” methodology, it was probably the former.

It was a mess is what we’re saying. But, hey, seeing as how Spider-Man was a 100-yard Hail Mary—or a desperate Fastball Special, if that’s more your speed –

Marvel

–it’s not that surprising no one actually remembers what happened. The wondrous web-slinger, after all, was, at the time, just one more superhero out of literally dozens that might or might not work out.

The only thing everyone does seem to agree on is that Ditko created the costume and web-shooters Spider-Man still wears today. Well, everyone except Jack Kirby, that is—and for, like, a while. Which forced Steve Ditko to, in 1990, go straight Alexander Hamilton on Kirby’s ass and show up with philosophical, passive-aggressive receipts.

Marvel

Somehow, out of this toxic cesspool of unmatched creative brilliance, ten pages of genre-changing spider-story showed up, ready to be crammed into the last issue of an entirely inconsequential comic series—and Martin Goodman still didn’t want to publish it.

“Martin told me three things that I will never forget,” Stan Lee later said. “He said people hate spiders, so you can't call a hero ‘Spider-Man.’ Then, when I told him I wanted the hero to be a teenager … Martin said that a teenager can't be a hero, but only a sidekick. Then, when I wanted him not to be too popular with the girls and not great-looking or a strong, macho-looking guy, but just a thin, pimply high-school student, Martin said, ‘Don't you understand what a hero is?’”

Turns out, Lee and Ditko did—and maybe more than anyone else.

Spider-Man, Spider-Man, Does Whatever An Angsty Teenager Can

Marvel

Amazing Fantasy #15, despite no one wanting to wipe their ass with the title before, ended up being one of 1962’s best-selling comics, and is still setting records today. So rather than simply reinstate Amazing Fantasy with Spider-Man headlining, letting Lee and Ditko put out the #16 they’d been working on—a la Thor and Journey into Mystery—Marvel went ahead and gave Spidey his own book entirely.

Y’know, eventually.

Amazing Spider-Man #1 didn’t debut for six months, until after Goodman got a look at the sales numbers for Amazing Fantasy #15, as well as a flood of fan mail. The wait didn’t seem to hurt Spidey’s popularity any, with Amazing Spider-Man selling well enough to bump the book from every other month to monthly and then running uninterrupted from 1963 to 1995, only officially ending with issue #700 in 2018.

So what precisely made Spidey so special?

Well, everything—literally all those reasons Goodman had for not publishing him. Spider-Man was a teenager at a time when the most popular characters were adults. But he wasn’t a sidekick like Bucky or Robin, or part of a team like the Human Torch; in fact, he didn’t have anyone to look up to or help him out. Spider-Man was his own hero and, more importantly, his own person—flaws and all.

Despite the wall-crawling and proportionally powered punches, Spider-Man was (and arguably still is) the most human superhero ever published. Amazing Fantasy #15 spends an equal amount of time with Peter Parker as it does with the alter-ego in the tights—and even then Spidey basically screws up in every panel.

Look at everyone else around in the early '60s: Superman was the strongest and the best of us; Flash was the fastest; Bruce Wayne was the richest, the greatest detective; the Hulk could punch a tank to death; Reed Richards could outsmart Galactus. Hell, Thor and Wonder Woman were literal gods. Even Johnny Storm, the closest comparable character, was cocky and handsome as finely-sculpted shit, a teen idol.

But Peter Parker was this scrawny nobody, a science nerd when that still meant you were getting shoved into lockers. He lost almost as much as he won. He was angry, made terrible decisions, doubted himself constantly, and—very much like spiders and Goodman’s complaint—was vilified by J. Jonah Jameson and the public at-large. Even the Human Torch thought he was a joke.

Marvel

Teenagers and college students—at the time, comicdom’s main audience—had never seen themselves and their struggles reflected in the pages of a comic book. Heroes were heroes, after all: they always won, and they definitely didn’t worry about not being able to find a date to the dance, or covering their rent. The whole point was that heroes were better than the regular schnooks they protected—but Spider-Man wasn’t.

Steve Ditko played up all of this. Even in the costume, Spider-Man was scrawny and wiry at a time when heroes were built like brick shithouses. He wore a mask that covered his whole face, because, as Ditko explained, “it hid an obviously boyish face.” His costume was ornate, distracting, because Peter was only ever pretending, trying to trick himself into believing he was a hero, even as he saved the day. Plus, as repeated repeatedly in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, anybody could see themselves in the costume.

Ironically, the constant (and steadily increasing) feuding between Ditko and Lee helped cement Spidey’s personality. Lee talked a good game, but he still wanted a quippy web-slinger—a hero. Ditko, meanwhile, on his own Ayn Rand-ian Objectivist bullshit, wanted to show a wallflower self-actualizing himself into an Übermensch. He purposely drew Peter Parker looking angsty and agonized outside of his costume, so Lee couldn’t be clever and crack jokes. This dichotomy—of a mask letting an anguished teenager finally cut loose, at least until he got a pumpkin bomb in the face—became the cornerstone of the character.

And just about every other superhero, Marvel or otherwise, followed suit.

With Great Power There Must Also Come—Great Responsibility!

Marvel

Here, in the wisecracking superhero-saturated future, it seems strange, but it’s impossible to overstate how downright radical Spider-Man was. Comic books just didn’t do what Stan Lee and Steve Ditko did—and that’s precisely why it worked.

The '60s counterculture is remembered for all the sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll, but comic books were actually a huge part of it, too—and Spider-Man showed up at exactly the right time. No one wanted to read about Superman crossing his enormous arms over his enormous chest and telling them not to get high. But a perpetually miserable teen always getting stepped on by society? Far out, man. In fact, a 1965 Esquire poll found that college students saw Spider-Man as a revolutionary icon, ranked right up there with Che Guevara and Bob Dylan.

Mashing up personal foibles with superpowers quickly became the Marvel way. And as the Silver Age was subsumed by the Marvel Age, everyone else got on board, too. The Teen Titans first debuted in 1964, a direct result of Spider-Man’s success. The '90s Static owes his inspiration to the webhead. Jason Momoa’s reluctant, smart-ass Aquaman? Yep. Even Superman—with Smallville, Superman & Lois, and 2013’s Man of Steel, flashing back to Clark’s bullied youth—isn't safe from Spider-Man’s influence.

And if a scrawny nerd from Queens can change the trajectory of the Man of Steel, well, 'nuff said.

Eirik Gumeny (@egumeny) is the author of the Exponential Apocalypse series, a five-book saga of sarcastic slacker superheroes, fart jokes, and assorted B-movie monsters … that also probably owes a debt to Spider-Man.

Top image: Marvel

For more Cracked deep dives, be sure to check out:

‘90S WEEK:

In The 1990s, The Simpsons Were A Danger To America

The '90s Officially Turned Gaming Into A Pop-Culture Fixture

How '90s Superhero Cartoons Prepared Us For The 'Cinematic Universe' Era Facebook Twitter Pinterest

The '90s 'Star Wars' Special Editions Kicked Off The Never-Finished Movie Era

3 Ways 90s Internet Changed Everything

MCU WEEK:

The 'Avengers' Comic That Basically Created The Modern Superhero Movie

Why Marvel Studios Is Branching Out Beyond Superheroes-- Sort Of

Marvel's Long And Confusing Path To Figuring Out Television

How Marvel Handles 'Black Panther' Is A Heartbreaking Task

All of the New Marvel Characters Getting Set Up In Phase 4

The Long, Stupid Road To A Watchable ‘Fantastic 4’ Movie

SUPERMAN WEEK:

4 Reasons Anyone Who Says 'Superman Is A Boring Superhero' Is Full Of It

4 Reasons O.G. Superman Is Even More Relevant Today

5 Superman Stories That Are Canon Kryptonite

4 Ways 'Death Of Superman' (Accidentally) Changed Pop Culture

4 Superman Movie Scenes That Were Dumb AF In Retrospect

JOKER WEEK:

The Early Obstacles On Joker's Path To Comic Icon

Why Do We Even Have Batman Movies Today? The Joker.

No One Was Ready For Mark Hamill's Joker ... Least Of All Mark Hamill

That Time DC Comics Turned The Joker Into David Bowie

A Dark Knight's Tale: How Heath Ledger Created A 21st Century Joker

The Weird Confusing Tale Of The Most 'Huh?' Movie Joker: Jared Leto

'Joker' Made A Billion Dollars, And That's Too Much Money To Ignore