4 Ventures the U.S. Government Created by Accident

This Fourth of July, let’s look back at the history of the U.S. government, whose every twist and kink was not in fact worked out by a group of founders sitting down in a room. Most programs came about long afterward, when someone suddenly said, “Hey. I just thought of a good idea.” Other programs, however, didn’t even start that way. They started following something much weirder.

The National Archives Were Supposed to Destroy Any Archives

By 1889, the government was getting bogged down by the accumulation of documents. Offices overflowed with the stuff, which probably served no purpose, and so on February 16th, Congress formed the Committee on Disposition of Useless Executive Papers to sort through the mess. The goal of the committee was to examine papers so they could be disposed of without any fear that we’d lost something of value.

Don't Miss

Naturally, this wasn’t a terribly prestigious committee to join. Congress would send unpopular members there as a punishment. Newspapers mocked the committee, calling it “the wastebasket” (as though the actual name weren’t ridiculous enough). Then in 1934, the committee ceased to be its own thing. From this point on, its function became a part of the new National Archives — a necessary institution because while a lot of these papers were marked ready for disposal, many of them weren’t and instead needed preservation.

via Wiki Commons

The Committee on Disposition of Useless Executive Papers worked slowly and in secret, often had too few members and sometimes had none at all. Still, it accomplished something few other government projects do: It ran at a profit. During the 1920s, it regularly made hundreds of thousands of dollars annually in today’s money and sometimes more, just by selling the waste paper. They didn’t sell to data miners or even to paper recyclers. They sold the stuff as kindling.

The Santa Tracker Was Due to a Wrong Number

Every Christmas, NORAD — a joint military venture between the U.S. and Canada for tracking potential aerospace threats — runs a program they call “NORAD Tracks Santa.” Their website and social media accounts give updates on Santa’s supposed location as he moves across the world. Before the internet, they ran a hotline that anyone could call to check in on where Santa is during these same 24 hours around Christmas.

According to one theory, this tracker does not really release accurate data on Santa but rather invents data, as sharing his actual location would endanger his safety. We can’t confirm or deny that. Nearly as interesting as that potential revelation, however, is the story of how the tracker started. This goes back to the holiday season in 1955. Colonel Harry Shoup worked for the Continental Air Defense Command (NORAD’s predecessor) and had an actual red phone at his home for major national security emergencies. It rang one day, but rather than the Pentagon informing him of an attack, it was a child asking, “Is this Santa Claus?”

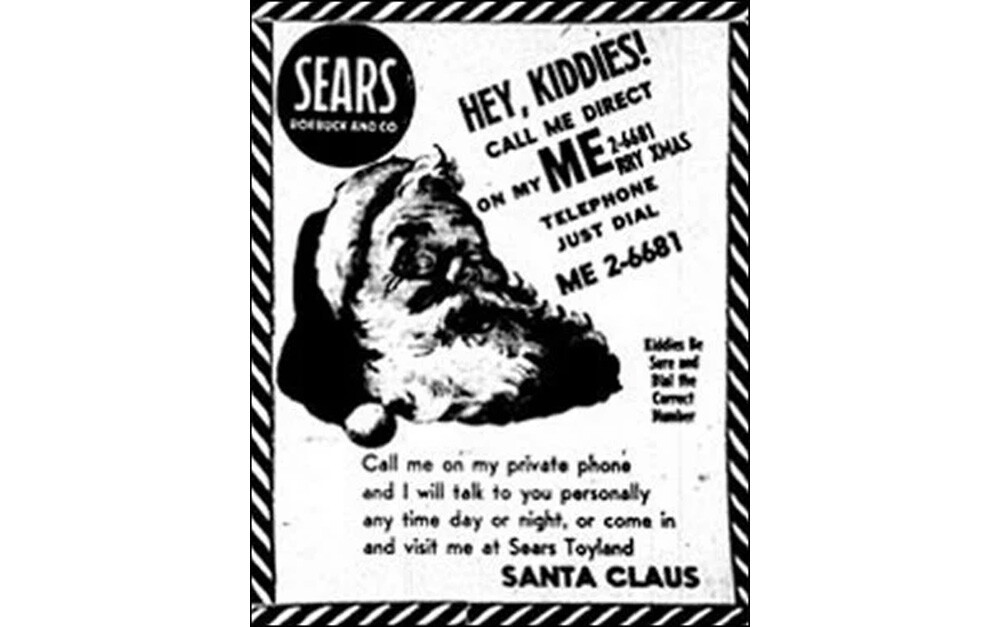

That year, Sears had put out an ad inviting kids to call a hotline, with Sears people answering the line as Santa:

The kid had reached Shoup instead, either because the ad had printed his number by mistake, or (as the more credible version of this account goes) because the kid had dialed the number wrong. Either way, reaching Shoup was a weird bit of serendipity. It gave Shoup the idea for the Santa tracker, which the military announced with the following statement: “CONAD, Army, Navy and Marine Air Forces will continue to track and guard Santa and his sleigh on his trip to and from the U.S. against possible attack from those who do not believe in Christmas.”

Truly, this is a heartwarming story, of the time the military used mainstream religious identity for PR and to portray all outsiders as godless enemies.

‘Enemy of the State’ Created the Surveillance It Sought to Prevent

Speaking of how surveillance can be fun, let’s talk about the 1998 Will Smith movie Enemy of the State. Smith uncovers a conspiracy, and in an effort to cancel him, the government either hunts him down or runs a smear campaign against him, whichever’s more exciting from scene to scene. This involves slipping cameras in his home, installing bugs and putting trackers into his clothing, all of which would be unnecessary if he lived a few decades later and they could just take control of the smartphone he already voluntarily carries.

The movie also features one surveillance method that did not actually exist. It shows an NSA satellite that can zoom in and look down at just about anywhere. It’s a big part of the film and an even bigger part of the trailer. Sweeping shots from space down to rooftops are a lot more interesting visually than just watching dots on a map.

That kind of surveillance did not exist at the time. But among the millions of people who saw the movie in theaters was an engineer at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a government lab that researches nuclear weapons, biosecurity and something called Titan Laser. This engineer knew no satellite could surveil people like the one in the movie did. But, he figured, it sure would be cool if one could.

He immediately pushed the lab into what would become the Sonoma Persistent Surveillance Program, creating a technology called wide-area motion imagery. These cameras would often be operated by aircraft rather than satellites, but it was still a deliberate attempt to replicate the system portrayed in Enemy of the State. While this sounds sinister, a representative of the Defense Department, which assumed control of the program in 2005, told us, “I know we might seem imposing. But trust me, if we ever show in your section, believe me, it’s for your own protection.”

Hostage Takers Convinced the EPA to Make the Superfund Program

Superfund is the bafflingly cheery name for the EPA’s program to clean up hazardous sites. At its worst, these disasters render whole towns uninhabitable, leading to evacuations, upended lives and even vacations needing to be replanned. As you might expect, the program began following one specific disaster. However, it wasn’t a simple matter of the government looking at the problem and deciding they had to do something.

The disaster area was Love Canal, New York, which started out as a planned community before turning into a waste dumpsite. A chemical company buried thousands of tons of toxic waste and then sold the site to a school for $1. Kids grew up with all kinds of weird diseases, when they weren’t playing with rocks that spontaneously caught fire. The state recommended that pregnant women right next to the toxic waste move away, but to some people in town, that didn’t seem like quite enough to address the problem.

via Wiki Commons

In May 1980, residents learned that two EPA officials were staying at a nearby hotel. They invited the men to a meeting, to “talk.” The officials discovered too late that the meeting was at an abandoned house, and the residents of the town locked the doors on them and kept them as hostages, to get the government’s attention. They succeeded in getting attention all right: The FBI swept into town, cut the phone lines between the town and the outside world, and had a standoff till the residents released their hostages after five hours.

The residents then announced that President Jimmy Carter had to act within four days, or else. What “or else” meant, they didn’t say, and several of them went to bed fully clothed that night, reasonably assuming the FBI were still lingering in the area and were preparing to arrest them for having committed a crime against federal employees. But no one did arrest the residents, and in two days, the government agreed to pay to move the families out. Later that year, this relocation program was made formal and written into law.

Now, we’re not sharing this story to suggest that violent revolt is an effective solution every time you’re dissatisfied with the government. But, well, that’s kind of what the spirit of July Fourth is all about, isn’t it?

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.