5 Famous Stories About People From History That Are Really Just Myths

When you were young, you learned about how George Washington cut down a cherry tree, Ben Franklin flew a kite in a lightning storm and an apple hit Isaac Newton on the head. Then you grew up and learned none of those stories were true. You cursed your kindergarten teacher for feeding you those myths and gleefully accepted a new teacher — the internet.

Unfortunately, this new venture of yours — reading about all the crazy historical facts they didn’t teach you in school — introduced you to a whole lot of new myths. They’re fascinating and sound temptingly plausible, but they’re not true. Stay ever vigilant.

Myth: Marie Curie’s Books Are Now Stored in Lead

Don't Miss

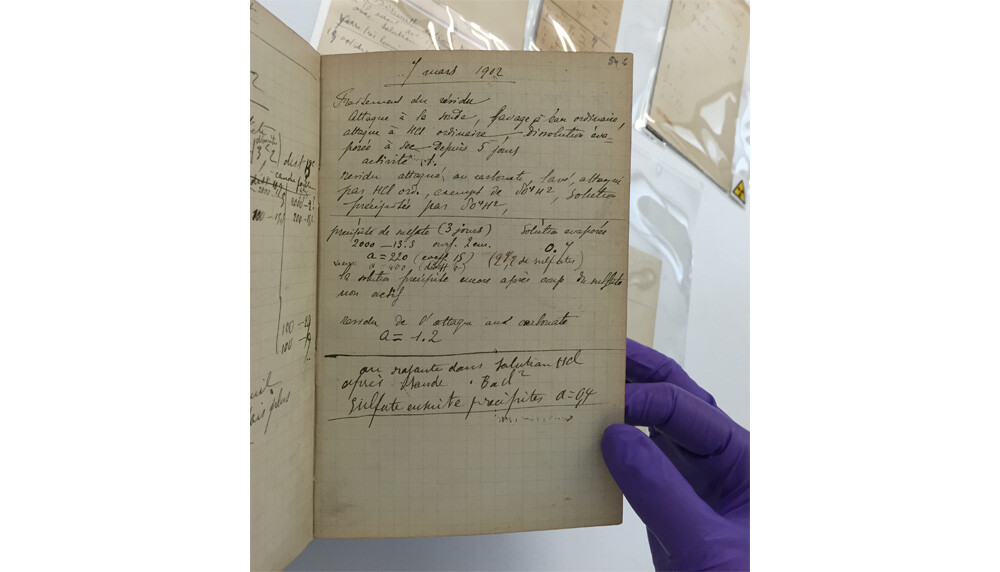

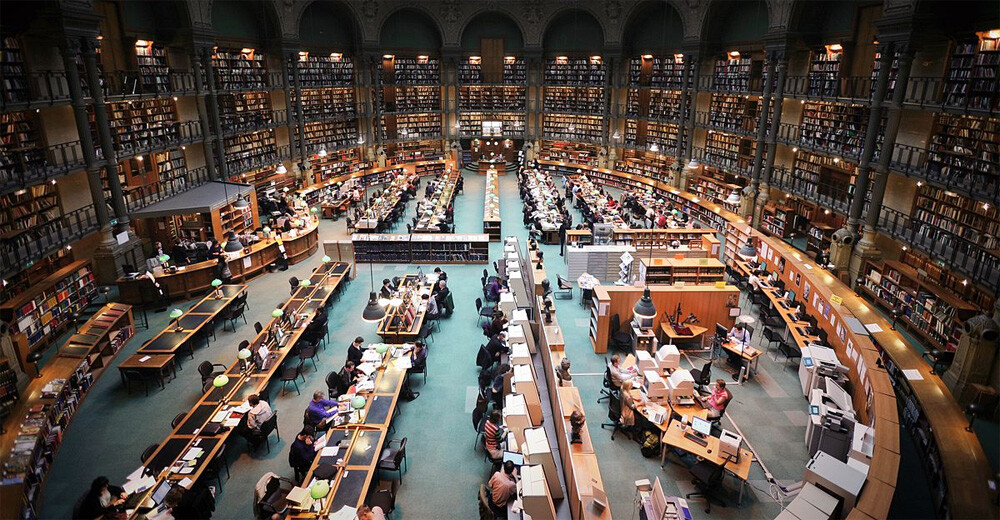

The Story: Curie’s radium breakthroughs won her two Nobel Prizes, but all that messing with radioactive substances also gave her the ultimate superpower: death. She died of some radiation disease, and she left behind a bunch of radioactive possessions. Her notebooks will be radioactive for another 1,000 years, and the French National Library (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, or BNF) stores them in lead boxes. To view them, you must sign a waiver saying you accept the risk.

The Truth: Yes, Curie studied radioactivity, and she was even buried in a lead coffin to protect us from her radioactive corpse. That said, when she was exhumed in 1995, the radiation levels inside that lead coffin were within the safe limits for any residence. It is possible that she never did suffer ill effects from handling radium. Ingesting radium is highly dangerous, resulting in terrible fates for those who used radium toothpaste or radium paint, but Curie may have never ingested the stuff, instead suffering from radiation thanks to her work with X-rays.

Now, about her notebooks being stored in lead. You’ll see that fact quoted on so many websites, and they always describe it the same way: Her books remain radioactive, BNF stores them in lead, you must sign a waiver to view them — and no one elaborates beyond that. No one has any photos of the lead boxes, just scans of the notebook pages. No one describes the experience of viewing the boxes, either firsthand or secondhand. You’d think someone would have taken a look. The BNF is in Paris, a pretty accessible city.

We were unable to visit Paris this week, but we reached out to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. They asked exactly which publication we represented. The answer must not have impressed them because upon hearing it, they ceased replying.

Jean-Pierre Vairon, from Paris’ Université Pierre et Marie Curie, had more luck. In 2012, for the centenary of Curie’s Nobel Prize, Vairon and several collaborators wrote for the Journal of Chemical Education about how Curie’s notebooks went to BNF in 1967. BNF decontaminated the papers and simply stored them in plastic. Yeah, turns out it’s possible to scrub radioactive material from some objects, though it’s not always practical.

Readers questioned this account, since they’d heard the books are being stored in lead for the next millennium. Vairon found the lead idea improbable, but he dutifully checked in with BNF, who confirmed that, no, the books are not stored in a lead-lined container, just in plastic, and they’re kept with the other precious archives. Here’s an account of how a British library dealt with another of Curie’s notebooks, without resorting to lead shielding.

Where did the lead factoid come from? Many sites today cite a 2011 article by the Christian Science Monitor. If you’re unfamiliar with the Christian Science Monitor, don’t let the name put you off — it’s very much a reputable source usually, but this article of theirs contains no original reporting, just the same info as everyone else plus general Curie biographical details. Other people may be getting the fact from Wikipedia, which cites 2005’s A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson, who is best known for writing funny travel books. Here, the name does give you a good idea of what it is: It’s a pop-sci book with too great a scope to be an authoritative source on anything. You shouldn’t cite it, for the same reason that you shouldn’t cite Cracked listicles or Wikipedia; you should look to their sources, if they have any.

We don’t know for sure where the fact came from, but with some of the other stories we’re looking at today, the origin for the fact is the funniest part...

Ernest Hemingway Never Wrote ‘For Sale: Baby Shoes, Never Worn’

The Story: Ernest Hemingway, he of famously sparse prose, was having lunch one time with several writers. The man had written The Old Man and the Sea in a hundred-odd pages, and he could be much briefer than that if he chose, he claimed. He bet he could write an entire story in just six words. The others at the table took him up on that bet, and Hemingway wrote the following on a napkin: “For sale: Baby shoes, never worn.” The other men paid up.

The Truth: No sources from when Hemingway was alive describe the bet. If he did make it and won with this story, it was a story he hadn’t composed but which had been floating around for decades. The earliest published account that Snopes could find of the bet came in the 1990s, within the lifetime of many people reading this. A 1990s play about Hemingway mentioned the bet, and it may have taken the anecdote from a recent writers’ guide called Get Published! Get Produced!: A Literary Agent’s Tips on How to Sell Your Writing.

via Snopes.com

The baby shoes story existed in various forms when Hemingway was just a boy. In the 1910s and 1920s, some versions substituted in “baby carriage, never used.” In 1917, a guide to short fiction suggested a hypothetical story called “Little Shoes, Never Worn.” This guide suggested that as the title, not the whole story, but it could have functioned as either. Since it’s already phrased as an advertisement, it would go without saying that the shoes were for sale, so this wording actual beat not-Hemingway’s, covering the entire narrative in just four words.

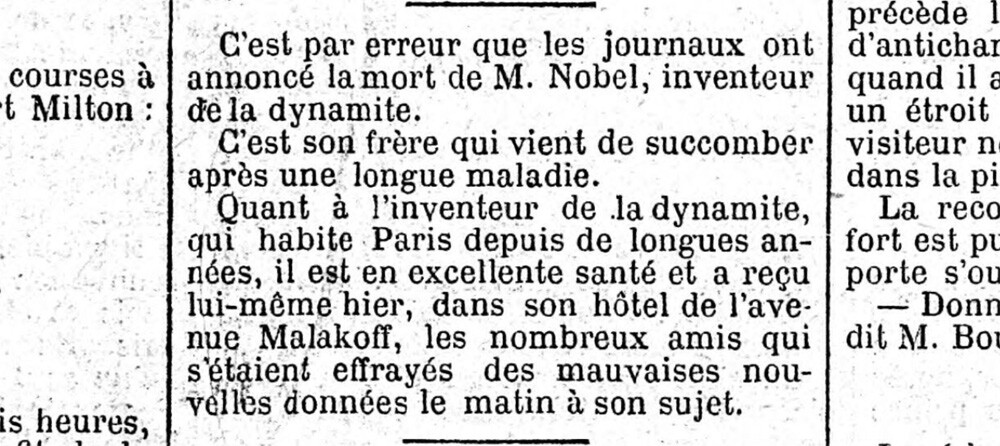

Alfred Nobel’s Inspiration for the Nobel Prize

The Story: Before he created the Nobel Prize, Alfred Nobel invented dynamite. That meant he had one heck of a late-career shift, and we got it because a newspaper mistakenly heard Nobel had died and so printed his obituary. The headline read “The Merchant of Death Is Dead.” While any premature obituary is going to give its subject a jolt, this one really gave Nobel a Christmas Carol-style shock and convinced him to be better man.

The Truth: As fun as it is to say “dynamite bad, peace good,” no newspaper obituary would summarize the inventor of dynamite by calling him the merchant of death. True, murderous anarchists used dynamite as a weapon, but dynamite was chiefly used in mining. If Nobel did nothing but invent dynamite (and his other famous explosive, gelignite), he would have contributed a great deal to the world. Dynamite gave us iron, copper and limestone. It gave us the Industrial Revolution and a vast increase in how good life could be.

If that scary obituary really existed, we should be able to track it down. The way the story goes, newspapers reported Alfred’s death because they’d heard his brother Ludvig died and confused the two Nobels, so the obituary should have come soon after April 12, 1888. Alfred lived in Paris at the time, and newspapers from then are archived by our old friends at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. But one French journalist’s trek through the obit archives there produced nothing.

When a Canadian editor contacted the Nobel Foundation about this story a decade ago, they replied that there had “never been found any documentation about this story despite all the research conducted. Yours sincerely, Nobelprize.org Team.” So, if you’re looking for a formal obituary called “The Merchant of Death,” none existed, and even if one did, we have no record of Nobel reading it and changing his life accordingly.

One newspaper, Le Figaro, did print something similar to what the urban legend says, and it's likely the source of the tale. Soon after Ludvig died, they stuck the following note at the bottom of a page: “A man who cannot very easily pass for a benefactor of humanity died yesterday in Cannes. It is Mr. Nobel, inventor of dynamite. Nobel was Swedish.” It’s similar to what the urban legend says — except it wasn’t a proper obituary, it was someone’s idea of a joke. Rather than interpreting it as an accurate prediction of his legacy, we imagine Nobel laughed (or took offense) at one random clown misunderstanding his work.

According to the Nobel Foundation, the idea of giving prizes to honor science and service to humankind may have come to Nobel in 1868. That was the year the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded him the Letterstedt Prize for “important inventions for the practical use of mankind.” They gave him this prize for inventing dynamite.

We Have No Proof Alan Turing Killed Himself

The Story: Alan Turing saved the world by cracking the Nazis’ Enigma code, and we did him dirty in return. After the war, Britain prosecuted him for homosexuality and forced him into chemical castration. That’s a terrible way to live. Turing ended up killing himself, in a fairy-tale manner: He injected cyanide into an apple then took a bite from the poison apple and died. Today, one famous tech logo shows a single bite taken out of an apple, as a tribute to pioneer Alan Turing.

Apple

The Truth: Maybe Turing killed himself. Crazy thing, though? No one ever tested that apple they found at the scene. They found him with cyanide in his system, and they just invented this story that he’d injected his apple with poison. His bedroom did contain a half-eaten apple, but he ate an apple every night. For all we know, that thing had no cyanide in it (other than the trace amounts of cyanide that all apple seeds have).

Turing died leaving behind not a suicide note but instead a list of tasks for him to do when the weekend ended. He had been using cyanide in his house for his experiments, electroplating spoons with gold. He might have taken in some cyanide accidentally. We don’t know what happened, but an inquest today would not have declared it a suicide based on the evidence.

So, we can’t give you any formal conclusion about Turing’s death. But we can debunk one story. The Apple logo? It never had anything to do with Turing. It’s just an apple. According to the logo designer, Rob Janoff, they stuck a bite in there because it offered a sense of scale; without it, the logo looked like a cherry. Stephen Fry claims to have asked Jobs personally about whether the logo represented Turing, to which Jobs replied, “It isn't true, but God we wish it were!”

Franz Ferdinand’s Assassin Never Stopped for a Sandwich

The Story: Gavrilo Princip managed to shoot Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, thanks to a sandwich. Earlier plans to assassinate the guy didn’t go so well, so Princip ducked into a café for a quick bite. By amazing coincidence, Ferdinand’s revised motorcade route passed right outside this café. Princip dashed outside and took his shot, resulting in World War I, and all of the world history that followed.

The Truth: Nevermind whether, if Princip missed that shot, the group backing him would have pulled off the assassination on some other day, or whether some other event would have sent all the dominoes tumbling regardless. A writer with the Smithsonian, Mike Dash, instead zeroed in on one unlikely part of this story: the sandwich itself. Because, you see, people in 1914 Sarajevo didn’t eat sandwiches.

The sandwich was invented in the 18th century, and by 1914, plenty of people in different parts of the world ate sandwiches, but not in Sarajevo. So, was “sandwich” a loose translation of some more fitting local snack? Dash looked into contemporary sources and couldn’t find any mention of Princip eating anything right before the shooting. Earlier accounts said Princip stood outside the deli rather than dining inside it. And far from serendipitously taking a wrong turn and driving right by the assassin, the motorcade went this way because that was the original scheduled route, which would also explain why Princip stationed himself there.

No 20th-century source seems to mention the sandwich story. Where did it come from? The earliest reference Dash could find was a 2001 Brazilian book called Twelve Fingers: Biography of an Anarchist. This book, though it describes the assassination of Ferdinand, is not a valid source for the simple reason that it is a novel. It’s a Forrest Gump-style tale of an assassin named Dimitri, who keeps bumping into historical figures, starting World War I, spreading the 1918 flu, etc. He also runs into Marie Curie, no doubt spilling radium all over her notebooks.

The article where Dash debunks the sandwich story lists several websites that mentioned the sandwich, including ours. We have to accept responsibility for spreading such myths. Still, it’s not as bad as the time we said — as a joke — that John Quincy Adams wanted to trade with the mole people, and the Smithsonian picked up the story, with the myth spreading from there.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.