5 Companies Who Made Money Selling Big Boxes of Nothing

According to leading economist Homer Simpson, money can be exchanged for goods and services. It can also be exchanged for nothing at all. This can take the form of gambling, taxes, theft or it can happen when you’re the victim of a scam. You pay $400 to some sketchy website to order a device that normally costs $1,600, and you receive a cardboard box containing only a bloodstained rock. You try to hunt down the company to give them a piece of your mind (or a piece of that rock, embedded in their mind), but they’ve vanished.

Some such companies don’t vanish, however. They live on, to laugh at their past malfeasance. Just like how…

Coke Cheated People by Selling Empty Bottles

Don't Miss

AriZona Iced Tea has cost 99 cents for 30 years, still managing to make money thanks to volume. Costco hotdogs have cost $1.50 for almost 40 years, because it’s in their interest to sell the stuff at a loss. But neither of these bulwarks against inflation are as crazy what Coca-Cola originally managed to do. Coke cost 5 cents a bottle when it first came out in 1886, and it still cost that much over 70 years later, in 1959. This price persisted, not merely through inflation that reduced the worth of a nickel to one-third of what it had been but also through monumental changes in absolutely everything worldwide.

Universal Pictures

For a long time, the price stayed low thanks to complicated contract issues that we won’t bore you with right now. Then, Coca-Cola finally decided they really had to raise the price, no matter how iconic the nickel price tag was, but they couldn’t. The problem was they now sold loads of their bottles through vending machines, and vending machines at the time didn’t add coins up to calculate sums. They simply accepted nickels and returned drinks.

To raise the price, they’d have to make new machines, which exchanged drinks for dimes — and even if they were willing to put up the massive initial cost to do this, doubling the price was too much and would scare off almost all buyers. So, they sought to raise the price to 7.5 cents, and to build vending machines that would accept a 7.5-cent coin. Of course, there was no such thing as a 7.5-cent coin, but Coke asked the U.S. Treasury to mint one.

The Treasury turned them down. People already had ways of buying items that cost more than a nickel but less than a dime (they could use pennies, multiple pennies), and it wasn’t the government’s job to reorganize the currency system around the limits of vending machines.

In time, stores did raise the price of a Coke by a few cents, and the company later took the plunge and made vending machines that charged a dime. But for a while, they managed to raise the effective price on each vending machine bottle using a most evil trick. They’d insert some empty bottles in every machine.

One out of every eight bottles that the machines dispensed were what Coke internally called “blanks.” Get a blank, and you’d assume it was a mistake, curse your bad luck and buy another bottle for another nickel. One blank for every eight legit bottles raised the effective price of a real bottle to 5.625 cents — which, honestly, doesn’t sound nearly high enough a profit increase to justify such shenanigans.

The Christmas of No ‘Star Wars’ Toys

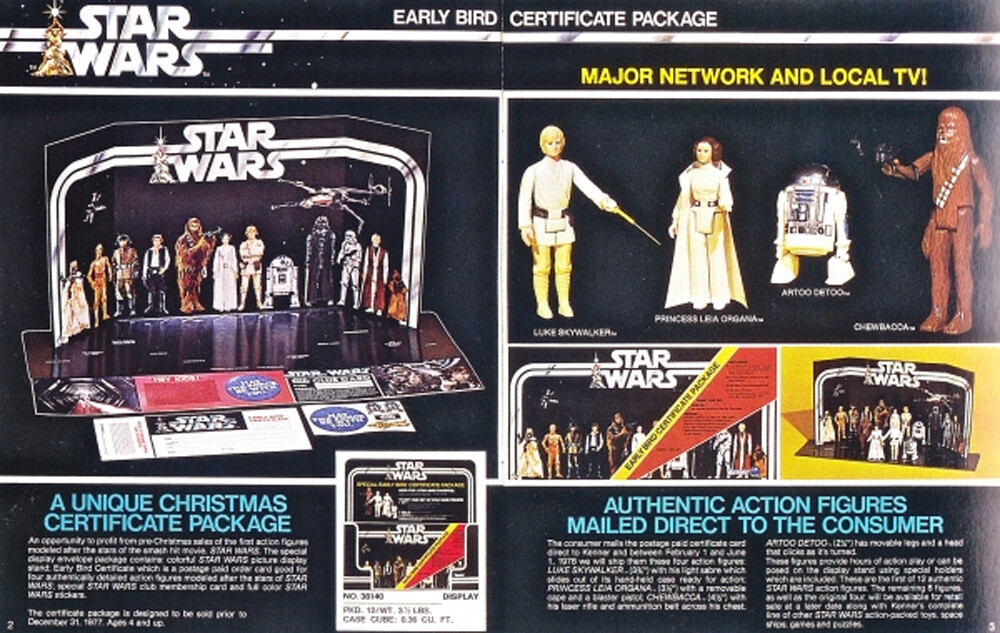

Star Wars is famously a merchandising empire, promoted by ancillary movies and TV shows. We’ve told you about how George Lucas made a fortune by forsaking $350,000 in director fees for personal ownership over merchandising rights worth billions. But if you were a parent looking to line Lucas’ pockets during the 1977 holiday season, you might have had some trouble doing so. The company that made the Star Wars toys, Kenner, underestimated demand and ran out.

There was no physical way for them to manufacture all the action figures people wanted to buy. So, instead, they sold empty boxes, for the price of actual toys. Each box contained a standup backdrop, where you could pose your action figures... if you had any, which you didn’t. As for the action figures kids actually wanted, Kenner said they would send them once they were ready, sometime in the next six months or so.

Kenner

The action figures, once they arrived, would go on to be worth a lot of money, and even the empty boxes are worth a lot today. But kids that Christmas didn’t want collectibles they could leave sealed to appreciate in value. They wanted toys, and they wanted them now.

Wonder Woman’s Invisible Jet

Many years after the Star Wars incident, Mattel put out their own toy boxes containing no toys. The packaging advertised Wonder Woman’s invisible jet, and the box contained... nothing.

This began as a 2010 April Fool’s joke — for the last decade or so, no one has ever really pranked anyone for April 1st, and “April Fool’s joke” is now a phrase that means “humorous corporate promo.” Mattel stuck up a Facebook post claiming to advertise the upcoming non-toy, but they didn’t really plan on selling it, because that would be stupid. Then they received inquiries from interested buyers. The buyers knew the box would contain nothing real, but a mystery box in Farmville also contained nothing real, and Facebook users bought tons of those.

So, Mattel made the empty boxes and sold them at Comic-Con for five bucks each. They included hidden weights in the box to give the feel of containing something. Let’s say that this was commitment to the bit rather than a genuine attempt to fool anyone.

Invisible Goldfish

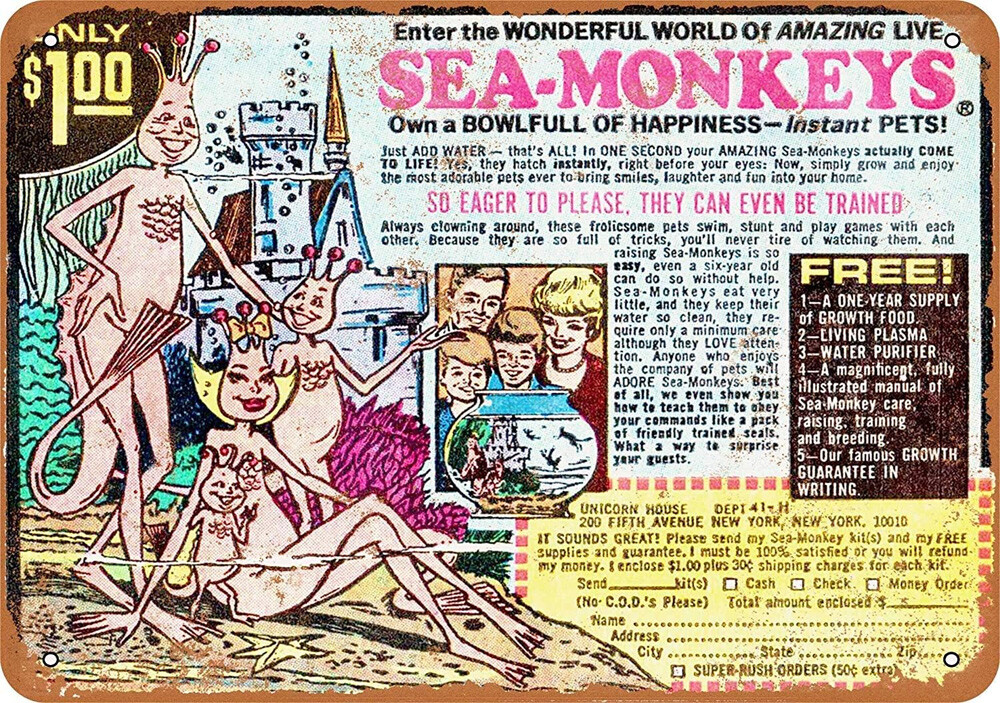

Other toys really did seek to fool buyers. In the 1950s and 1960s, toymaker Harold von Braunhut received patents on 196 different inventions, and the primary appeal of several of these was their ability to trick customers into thinking they were worth buying. He sold X-Ray Spex, glasses that let you see THROUGH PEOPLE’S CLOTHES (they did not actually let you see through anything). He sold sea monkeys, advertising them as humanoid mer-people, disappointing children who’d open the package and see tiny brine shrimp.

He also sold something he called the Invisible Goldfish. It was a bowl with sea plants and no fish. You’d never see the invisible goldfish, said the packaging. Sure enough, no one ever did.

The $18,000 Sculpture

We don’t want to be one of those people who dismiss all art as fraud. When people call some seemingly simple painting a work of genius, sometimes, it really is a work of genius.

Other times, it really is nothing. In 2021, an Italian sculptor actioned off a piece that he called Io sono, or I am. It was an immaterial sculpture — i.e., it was nothing. But he said that this nothing should be displayed in an area 5 feet by 5 feet. Someone bought it at auction for $18,000.

This wasn’t the first time an artist sold nothing. We’ve told you before of when Yves Klein sold “imaginary spaces,” in exchange for gold that he vowed to destroy. The difference is, Yves Klein was famous, so even if you refused to see any value in the art, it held value as an investment. The receipt for one of those imaginary spaces later sold for more than $1 million. But this Italian sculptor, Salvatore Garau? His name alone doesn’t mean anything, and his biggest claim to fame appears to be selling Io sono.

Maybe this was all a conspiracy, the buyer was a confederate of his and the real goal here was to make Garau famous. If so, this story is the real empty box being sold. Either that, or Salvatore Garau is the empty box, because what is celebrity other than a box of nothing that we just agree has value?

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.