6 of the Craziest Adventures Ever All Happened to the Same Guy

You probably never learned about Robert Bartlett back in school when they taught you about explorers. Bartlett didn’t hit any of those traditional benchmarks for what makes an explorer significant, like being the first man to discover Cleveland. But the story of the Age of Exploration isn’t just a list of names and discoveries (which, when you look closely, often don’t even deserve they attention they’re given). It’s a story of adventure. And Robert Bartlett had some truly crazy adventures, any one of which earn him a spot in our Big Book of Badasses.

His Ship Caught Fire on the Way to the North Pole

Bartlett, hailing from Newfoundland, went on many expeditions to the Arctic starting in 1898. His first voyages were with Robert Peary, whom you might know as the first man to reach the North Pole, and their early time together didn’t go so well. On their initial 1898 trip, it was young Bartlett’s job to hold a frostbitten Peary down as a doctor amputated eight of his toes. Go through something like that with a man, and the two of you will be tight for life.

The next time they sailed together, Bartlett captained the ship. This ship, the SS Roosevelt, caught fire on the way to the North Pole — and though we lured you in with that detail, it was probably the least exciting of the many troubles they had during this expedition. The ship later became stuck in the ice, and Bartlett buried 20 sticks of dynamite to free it. Along with breaking the ice, the explosion blew a giant hole in the side of the ship.

They repaired the hole but soon realized they wouldn’t make it all the way north, so they turned back. The ship hit icebergs and filled with water, the pumps failed, and Bartlett had to smash down walls so the water could reach the one pump that still functioned. The rudder broke off repeatedly, and the main mast once fell and narrowly missed crushing several people. Then, still a thousand miles from home, they ran out of coal. They switched to burning seal blubber. When that failed, they ended up ripping up wood from their own hull to feed the furnace.

Peary also rode Bartlett’s ship on his eighth Arctic voyage, the one that actually reached the North Pole. When their sleds stood just 135 miles away from their goal, he told Bartlett to go back to the ship. “Perhaps I cried a little,” Bartlett later said. He walked five miles north, just on his own, then went back to the ship as instructed.

No one’s quite sure why Peary demanded Bartlett go back. Maybe it was because Bartlett wasn’t British. But given that Bartlett was the best navigator in the party, and a lot of controversy followed over whether Peary really did make it to the North Pole this trip after all, some speculate that maybe Peary wanted to claim victory over the Pole without anyone in his party being able to contradict his story.

The Summer of 59 Bears

Sometimes, Bartlett journeyed in search of new lands, and sometimes, Bartlett journeyed in search of new peoples. In 1910, two millionaires contracted him to take them north to let them kill as many polar bears and musk oxen as possible. One of the guys was Harry Whitney, who was an Arctic explorer himself. The other was Paul Rainey, who’d go on to record a hunt of his in Africa and make it into one of the highest-grossing films of the decade.

Today, the concept of trophy hunting has a bad reputation. But that hunting trip these guys went on in 1910? It was, by most measures, a lot grosser than trophy hunting. They didn’t target individual animals, kill them and cut off their heads to mount as souvenirs. They went out each day with 100,000 rounds of ammunition and shot wildly at everything, noting their kills with pride but not even bothering taking anything from the bodies. They killed 59 polar bears on that trip and killed so many musk oxen and walruses that they gave up counting them.

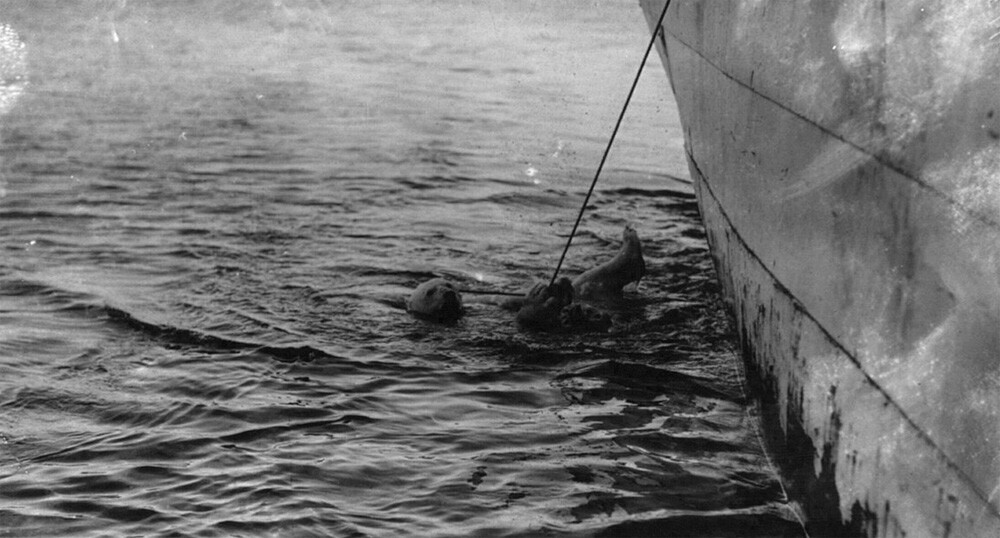

Bartlett didn’t think highly of all this. He described it as “hunting, if you can call it that.” He had another mission during this expedition, however: capturing animals alive. This, too, would mark him as the villain in any cartoon, but at least it offered more of a challenge. He bagged a 1,200-pound polar bear, taking it alive by slipping a lasso over its head by hand and letting it tow the ship till it tired itself out.

Then he lured the bear into the hold and tossed 18 pounds of chloroform on it. No one had ever captured a full-grown male polar bear before, and this one, named Silver King, would live another 20 years. During the same trip, Bartlett also captured two baby polar bears, two baby walruses and six baby musk oxen, which must have made for quite a noisy return voyage.

He Trekked 700 Miles to Save His Stranded Men

An expedition sets sail toward the Pole. The ice becomes increasingly troublesome, and the men leave the ship and build igloos. Then the ice totally tears apart the ship, which sinks. While most of the crew set up long-term camp, one man turns back toward the equator, journeys 700 miles, finds rescue and returns with help.

Incredibly, the above paragraph accurately describes two separate, unrelated incidents. One was the Shackleton Expedition, which set off in 1914 to Antarctica. The other was the last voyage of the Karluk, a ship that sank earlier that very year. Everyone in the Shackleton Expedition survived. The crew of the Karluk were not quite as fortunate.

Bartlett was captain for this voyage, but expedition leader Vilhjalmur Stefansson brought him on late. That meant Bartlett didn’t have a chance to pick his own crew, and he looked with disapproval on the inexperienced lot he ended up with, which included a drug addict, someone suffering from VD and some guy who broke the rules by smuggling a bunch of booze onboard. Bartlett also didn’t get to pick the ship. The Karluk was “absolutely unsuitable to remain in winter ice,” Bartlett wrote in code to the Navy before they set off, in a message asking for advance help in case of a probable disaster.

He was right. The ship got stuck, and Bartlett, predicting the worst, unloaded most supplies, so they’d still have their food when the ship splintered apart and sank. Around this point, Stefansson took off and never came back. Maybe this was his way of abandoning the crew, or maybe he genuinely went hunting but couldn’t locate them afterward, since the moving ice took them many miles from where they’d last been. The crew made camp on an island, and years later, Stefansson would come back to this island — to try to colonize it. This later, 1921 venture arguably constituted “invading Russia,” and nearly everyone in that expedition died.

Back to 1914 now: Bartlett organized a couple different parties to go off in different directions. None of them fared great; we found the frozen corpses of one party a decade later. Finally, Bartlett headed out himself, first with a couple scientists and one sailor, then (after they all got injured) just with one Inuit named Kataktovik. They marched through Siberia to Alaska, 700 miles, through temperatures 50 below zero. After a month, they reached a town, where Bartlett caught a boat to a bigger town, and a month after that, he got himself a ship capable of rescuing the Karluk’s crew.

He also sent a message to a different ship that was closer to the wreck, and this ship ended up reaching the gang first, and then they all transferred to Bartlett’s ship once the two vessels met. Not all the men had made it, though. They’d been stranded for six months, and besides the usual woes of cold and starvation, their diet had given some of them a fatal kidney disease called nephritis. They’d kept one of the corpses inside their tent, and the smell had been awful, and probably didn’t help the remaining men’s health much.

Eleven members of the crew died before rescue. The Karluk had a few surprising survivors, however. One Inuit hunter in the expedition had brought his wife and two daughters along, and they all survived. That included the younger daughter, Ruth, who turned three years old while in the camp, and who’d go on to live till 2008. She escaped the ordeal with just a scratch — from the ship cat. That cat was a kitten when they launched, and it also survived, got rescued and lived for a long time afterward.

Murder, and the Made-Up Island

We mentioned before that Robert Peary could be somewhat less than reliable. During one of those polar voyages with Bartlett, he claimed to have sighted a distant landmass, which he named “Crocker Land.” In 1913, a ship headed north in search of Crocker Land, but they were chasing something that didn’t exist. Peary had sighted nothing. He’d just made this claim to earn the favor of his patron, banker George Crocker.

The expedition set up a base in Greenland, a few injured men remained there, and soon, the trekking party was down to four people: Donald Baxter MacMillan, Fitzhugh Green and two Inuit (Piugaattoq and Ittukusuk). MacMillan was convinced he saw the island they sought, and though Piugaattoq told him it was just mist, the men pressed on. No matter how many miles of sea ice they crossed, they never got any closer to the island. They were chasing a mirage.

They finally abandoned that search. As they tried to find a good route back to their Greenland town, Green and Piugaattoq split off in one direction. During the return trip, Green shot Piugaattoq in the back, killing him. We don’t know why. Maybe Green feared Piugaattoq was abandoning him and shot him to stop him, but fatal gunshots are a pretty poor way of retaining a trekking partner. Piugaattoq’s Inuit friends later said Green killed him in a failed scheme to get the guy’s wife. No one prosecuted Green or investigated the murder.

You might now be wondering where Robert Bartlett was during all this. Bartlett wasn’t part of the Crocker Land Expedition at all. No, Bartlett was the guy who sailed in afterward to rescue the stranded men. This was no easy feat. Three other rescue ships had tried and failed to make the trip and themselves became stranded in the ice. This rescue process stretched out so long that Green and a few others already got out by dogsled to Danish colonies, but MacMillan, whom Bartlett saved, was stuck there for three years. If he’d had to choose between staying put and sleighing with Green, we think he made the right decision.

The Drunken Laundry Wagon Accident

Around 1920, Bartlett put together his biggest sailing proposal yet, one that was so expensive, he’d need the Navy to back it. The Navy refused. They figured that they should be funding aerial flights over the Arctic, not sea voyages, since planes excite the public, even though planes can’t examine the surface or the depths the way a ship can.

With no proper voyages over the next few years, Bartlett lost a sense of purpose and developed a drinking problem. It’s possible he’d battled alcohol before as well, which explained why he’d been so angry when someone sneaked the stuff aboard the Karluk. Though Prohibition was in effect at this time, that posed no obstacle. He was welcome in the homes of many millionaires with liquor hookups, hosts who’d get Cap’n Bob drunk and then laugh at his stories.

In 1924, he was crossing 44th Street in New York (drunk, likely) when a laundry wagon hit him. It broke his leg and a bunch of his ribs and put him in the hospital for three months. Despite all his adventures, this collision with a truckload of crusty 1920s bloomers was the most serious injury he ever suffered. Not long afterward, newspapers printed Bartlett’s obituary.

He wasn’t dead, though. He’d recovered from the laundry injury, gave up drinking, got his hands on a schooner, went out on another expedition and now was presumed lost at sea. But he eventually arrived back in America, read the obituary and went on to lead 20 further scientific expeditions over the remainder of his life.

He Took a Break and Became an Actor. What Could Go Wrong?

In 1930, a director named Varick Frissell approached Bartlett about a movie role. The movie would be about a newcomer joining a seal hunt, and the production would mount an actual voyage north and shoot on location. That would be impressive even now, but back then, it was nuts. Hollywood normally recorded audio exclusively on soundstages in these early days of talkies. For further authenticity, they wanted to cast Bartlett, a famous real explorer, as the movie’s sea captain.

Newfoundland-Labrador Film Company

It took time from Bartlett’s own expeditions, but the price was right.

The script had the characters scramble to survive a shipwreck. Frissell wouldn’t need to crash an actual ship to shoot these scenes, though. No, when the production of this movie ended up crashing a ship, it was totally by accident.

Filming was nearly done, but Frissell headed north one last time to grab some extra footage. His ship exploded. That was thanks to the icebreaking blasting powder catching fire, possibly because someone lit their pipe near it. Picture that misadventure Bartlett and Peary had with the dynamite, only much worse. How much worse? Twenty-seven people died in the explosion, including Frissell himself.

Newfoundland-Labrador Film Company

Obviously, there was no chance they could release the movie now. Except, no: They absolutely did release it, renaming the film after the exploded ship and including a new foreword about the explosion. “This is the picture that cost the lives of Varick Frissell and 25 others in the Sealer Viking Disaster,” read posters (which didn’t even get the death toll quite accurate), while Howard Hughes launched a new chain of cinemas with the film and proclaimed on billboards, “26 men died to open the Hughes-Franklin Studio Theatres.”

The Viking was the most deadly movie production in history. It’s kind of amazing that in all our many articles about movie accidents, we’ve never told you about it till now. And unlike so many movies of the era, The Viking is no lost film. The entire thing is online today. Watch it, to see some actual footage of the Arctic and ships, footage that’s almost a century old — and to see and hear Robert Bartlett as Captain Bob Barker.

Yep, Bartlett really did make it into the movie, and he made it through the filming process unscathed. His first line in the film marks the fictional ship as very different from the one they sailed while filming. “Sorry, my son,” he tells one hopeful recruit that he rejects for being too small. “You know my reputation. I never lost a man. I can’t take chances.”

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.