5 Frauds and Liars Everyone Should Have Seen Coming

In 2022, we watched fraudsters get exposed and then cathartically crash and burn. NFTs got a lot of attention before collapsing; crypto houses shut down, and some crypto hucksters got arrested. Tech billionaires (and other billionaires) were shocked to find people not believing their spiels, and their fortunes shriveled. People entered politics and lost on a platform of denying past elections. Alex Jones got fined $1 billion.

On TV, we tuned in to The Dropout, WeCrashed and Inventing Anna. And even the Liver King, a man whose every action inspired trust, was revealed to be a liar.

Don't Miss

Maybe we’ve wised up now and will never again be fooled. If so, that would make us different from everyone else in the history of the world.

The Monkees Just Made Up Their Success, and Everyone Believed Them

The Beatles, after having a ton of success as a band, put out a series of comedy films. A little later in the 1960s, some producers decided that was a very inefficient way of merging music and comedy. So they streamlined it, by proposing a TV sitcom called The Monkees and then creating a band to star in it.

When the Monkees recorded music, you’d sometimes hear the voices of bandmembers Davy Jones or Micky Dolenz, or sometimes, you’d just be hearing random uncredited session musicians who were pulled into the studio that day. Treating them as a real band required some suspension of disbelief. That must be why they had hits called “I’m a Believer” and “Daydream Believer.”

But we’re not here to break the story that The Monkees were a “fake” band. Everyone back then knew what they were. We’re here about a more specific lie.

In 1977, in an interview, Mike Nesmith recalled their success from a decade before and said that in 1967, the band sold over 35 million records, more than the Beatles and Rolling Stones combined. The interviewer transcribed that fact and included it in his profile. In the years that followed, that was the go-to stat for summing up the Monkees’ success, repeated by such publications as the Washington Post and Rolling Stone.

Nesmith just made that fact up. 1967 was huge for them, true. Three hit albums with combined sales of 10 million made for a monumental accomplishment. But no, they didn’t outsell the Beatles and Stones combined that year; that would have been insane. Music sales were all tightly tracked back then and were a bigger deal than today, so it should have been simple to verify this, but no one did, and so the lie became lore.

According to Nesmith’s later recollections, he started that interview by telling the Australian reporter that he was going to be peppering his answers with lies. If so, that makes this even funnier, but we don’t know if we should believe him. The man was a confirmed liar.

Rebecca: The Musical Was Backed by Imaginary Rich Men

You might be surprised to learn Rebecca got a musical adaptation. It’s not exactly a lighthearted novel. You may know it best from the Alfred Hitchcock movie, where hardly any characters break into song (another story by Daphne du Maurier, “The Birds,” also became a famous Hitchcock movie). Nonetheless, Rebecca got a German musical, the same language that gave us the Rocky musical and that vampire musical built around “Total Eclipse of the Heart.”

GuentherZ/Wiki Commons

In the 2010s, Broadway producers wanted to bring the show to America. Help came from one Mark Hotton, a middleman representing four foreign investors willing to put up millions. The Broadway folk didn’t look too closely into these investors. When someone offers you millions of dollars, there’s no chance they’re cheating you, right? When they ask you for millions of dollars, that’s when you suspect fraud.

The investors — Hotton provided names and nonexistent home addresses — were all imaginary. This became increasingly clear as time went by without any direct communication with the investors and without any of the promised money coming in. With producers becoming especially impatient over one of the delayed payments, Hotton announced that this investor, Paul Abrams, had tragically died of malaria in South Africa. Entertainment reporters found no official reports of this death. Abrams’ one representative, beyond Hotton, was someone calling himself just “Wexler,” communicating through an email address that was only one-month-old.

United Artists

What was Hotton getting out of all this? For starters, he charged the producers $7,500 just for connecting him with the investors. Note: If anyone ever tells you that they have millions coming in from Africa and just need a few thousand to transfer it here, do not believe them. Hotton charged them other fees, too, adding up to over $60,000 (just a fraction of all the many millions he was promising, so it was a bargain of course). He also ran other grifts, charging $18,000 for an exclusive African safari with Paul Abrams, which never ended up happening.

This whole Broadway thing turned out to be just a side project to a far larger fraud, where he’d use the identities he’d invented for financial shenanigans too complicated to describe here. By the time the truth came out, the producers had already sold $1 million in tickets to Rebecca, and had raised a further $6 million from actual investors, but that wasn’t enough to stage the show. Before they had a chance to sort things out, years passed, and they lost the Rebecca rights. Still, a successful version of the play opened in South Korea in the meantime.

The Tech Firm That Stuck Lights on Empty Boxes to Fool People

Businessman Barton Watson referred to himself as “Barton Watson III,” even though he was the first in his family by that name. That should have been an indication that he was a fraud. If not that, other clues existed. For example, prior to the events of this story, he had been convicted multiple times of fraud, and had served two years in prison, for fraud. Such things, more often than not, suggest a history of fraud.

Ichigo121212/pixabay

Still, he founded a tech company called the CyberNet Group, and he convinced people it was making a lot of money. CyberNet resold computer equipment and claimed revenues of hundreds of millions a year. These sums pretty much all came from cooking the books, with the goal of getting more and more bank loans.

To convince creditors, CyberNet tried to look rich. Watson installed a wine cellar in the office, housing a million-dollar collection. He got a desk made of exotic wood and told people that it too was worth a million (it’s unclear whether it really was). He bought a Rolls Royce. When one client scheduled a visit to see if CyberNet really had the inventory they claimed, employees stuck blinking lights on empty server boxes to give the appearance of working equipment.

İsmail Enes Ayhan/Unsplash

Finally, in November 2004, investigators got wise and got a warrant. By this point, the company owed $110 million and had only a couple million in assets — when their belongings eventually went up for auction, the wine actually represented a significant chunk of the company’s worth. Watson stayed home from the office during the search. Then, late one Tuesday, he got drunk on a $700 bottle of wine and called 911, saying he had a gun in his mouth. This was no ploy for sympathy. After hours on the phone with the dispatcher, and with police now surrounding his home, Watson really did fire the gun and kill himself.

When confronting someone with suicidal ideation, people often say, “Think of those who’ll miss you. Think of your mother.” Certainly, Watson’s mother suffered following his death. She received two years’ probation for buying him the shotgun. She’d lied during the purchase, and apparently, that constituted fraud.

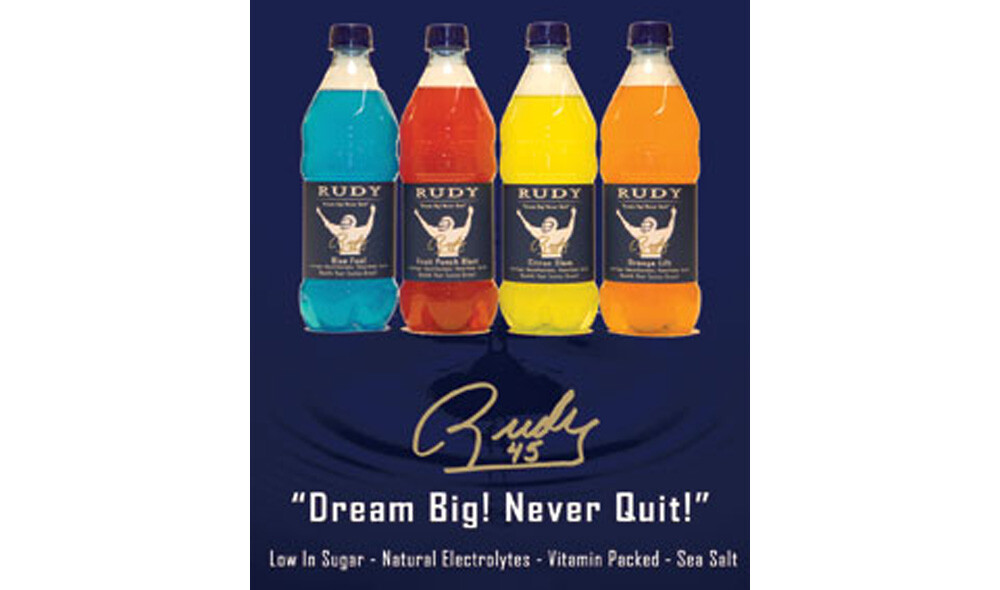

The Real-Life Rudy Ran A Multimillion-Dollar Beverage Scam

The movie Rudy was based on the real life of Notre Dame player Daniel “Rudy” Ruettiger. You might want to read about how the film was a sentimental, inaccurate version of what really happened. But if you really want to stop feeling inspired by Rudy, you should hear about what he did after “playing” college ball.

TriStar Pictures

Not all speakers are grifters. Only 80 percent are.

Rudy went on to sell a sports drink that bore his name. Wait, don’t walk away — there’s more. We wouldn’t blame anyone for capitalizing on their fame that way. The problem was the drink was just a token product sold by a company whose real goal was stock fraud.

The drink outsold Gatorade two to one in test markets, said promotional material. It beat Gatorade in taste tests, they said. In reality, it did neither, and those lies wouldn’t be enough to fool the buying public for long. The lies (and various other manipulation tactics) were enough, however, to quadruple the stock price of Rudy Nutrition in 2008. And maybe the company would have got away with it too, but then the company said, “Hey, let’s really lean into this and issue two billion more shares and try to sell them before the price crashes.” The SEC halted trading, and then opened an investigation, which would take three years.

Rudy Nutrition

Rudy was no mere figurehead whom the other businessmen duped. He ended up having to pay a big fine on top of returning all his profits, and the SEC banned him from stocks and from ever running a public company again. One co-conspirator, meanwhile, fled to South Africa to escape arrest, but they captured him anyway, and the guy ended up in prison.

Today, you can no longer buy the drink. Which is too bad, because we’re sure many of you would love to open your mouth and guzzle a few big swallows of salty Rudy.

A Prisoner Arrived in America and Became Royalty

For a change in pace, let’s jump back in time and talk about Sarah Wilson, a maid in England in the 18th century. Wilson used to tell people that she was the “Princess of Mecklenburgh” or “Lady Countess Wilbrahammon.” Those sound like not just fake names but names she made up on the spot by looking at random things in the room. She still fooled people some of the time, using courtly knowledge she’d attained by working as a maid to one of the maids in the actual palace.

Wilson’s lies caught up with her — her lies, and the fact that she’d stolen a bunch of stuff, including a diamond necklace. The crown sentenced her to death. Then she received a reprieve and instead suffered a fate that many convicts faced: She was transported overseas to one of Britain’s colonies. Her ship reached the New World in 1771. A man named William Duval bought her as an indentured servant, which was a thing people could do back then.

Then Wilson escaped. And so started phase two of her life pretending to be royalty. Now many miles away from anyone who knew better, she kicked it up a notch and claimed to be Susannah or Matilda, sister to Queen Charlotte. As evidence backing her claim, she had a few jewels on her, as well as a painting of the Queen, done in miniature. How exactly she’d managed to keep these items on her person through her arrest and journey is a matter we will discreetly skip over.

Queen Charlotte didn’t have sisters named Susannah or Matilda. Even people who knew little about England might know that much. Also, people who knew a bit about royalty knew that if Queen Charlotte did have a sister, she should speak German, a language Sarah didn’t know. Still, she managed to fool plenty of people into thinking she was a visiting princess. She stayed in the homes of rich Virginians, and she convinced people to lend her money. She offered promises in exchange, giving her benefactors positions in the military or government. England never quite got around to honoring these promises.

John Trumbull

Wilson became famous enough that Duval managed to track her down and lay claim on her again. Even that didn’t end her adventures. She was soon free again, either having escaped again or having bought her own freedom. From here, the history on her gets murky, with reports of her popping up in several other different locations under several different names and titles.

Accounts agree on one thing, though: She was never captured or charged for defrauding all those wealthy Southerners of their money. For all we know, various people in America today who say their families have been here for hundreds of years could trace their lineage to this thief who turned herself into a princess. That would explain a lot, actually.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.