5 People Who Succeeded Because They Didn't Know It Was Impossible

Often, we like to tell you about people who are complete screw-ups, because that's relatable. And if you happen to not be a screw-up yourself, well, then you enjoy the story even more, as you can laugh at your inferiors who fail. But guess what: Sometimes, people succeed. Crazy, we know. And while most motivational stories are just preludes to asking you to buy some grifter's book, maybe the following stories really will motivate you. Go punch a bear in the mouth—we believe in you!

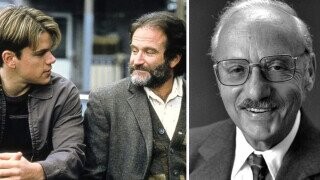

A Ridiculous Scene From Good Will Hunting Happened For Real

Good Will Hunting is about an unnamed character played by Matt Damon, a genius janitor who's also great at fighting and baseball and attracting the ladies. His only flaw is that he doesn't apply his genius, that's how genius he is. At the end of the movie, he chooses again not to apply his genius, but it's okay this time because he does it out of love.

The movie was written by Matt Damon himself, with help from his taller friend Ben Affleck, and as soon as you learn that, the movie's impossible to take seriously. Particularly silly is the opening scene. An MIT professor presents a graduate class with some proposed theorem, in the hopes that one of them might be able to prove it by semester's end—and if they do, they will surely go on to fame and fortune. Matt solves it effortlessly, because he's an expert in advanced math, as well as the history of economics and law.

Miramax Films

While the whole movie is Matt Damon's fantasy, this scene happens to be vaguely based on a real story. In real life, the solver of the tough math problem was a doctoral student, not a janitor, which is more believable. But the other details surrounding the incident make it sound even less likely than Good Will Hunting.

In 1939, George Dantzig arrived late to class at Berkeley and copied off the board what he thought it was the homework. It took him a couple days to formulate proofs for the assigned theorem, as they were harder than expected. Then he turned them in to the professor, Polish mathematician Jerzy Neyman. Six weeks later, Neyman got back to him (we can surmise that Neyman rarely actually read anything students submitted to him, making him a typical professor). He explained that the stuff on the board hadn't been homework problems at all but examples of statistical theorems thought to be unprovable, and yet Dantzig had proven them.

Of course, Dantzig then went on to a glorious career in mathematics, and the theorem's proof was his first published paper. First, though, he cut his doctoral program short for a while to volunteer for the Air Force during World War II. That's the sort of movie ending Matt Damon now wishes he went with. Meanwhile, Matt Damon himself went on to use numbers only for evil, shilling for cryptocurrency in an ad which was basically a recreation of this Good Will Hunting scene:

A Better Lightbulb Turned Out To Be A Lot Easier To Make Than People Thought

In the 1910s, General Electric had a tradition when it brought new engineers aboard. They would give the man an assignment: Produce a "frosted bulb." Frosted glass, in theory, would diffuse the bulb's light. That means the light would look less harsh when you're close to the bulb but just as bright when you're at a distance

A couple of the stories we're covering in this article have become urban legends, and the way this bulb story gets told, no engineer succeeded at making the bulb. Each time, they declared the endeavor impossible, at which point GE informed them that the company had known it was impossible all along, and this had just been a test. It's a much more wholesome story than the many tales of how other companies hazed their new recruits, as well as the harrowing tales of what happened to the GE employees who failed the test.

Then General Electric hired Marvin Pipkin. Marvin Pipkin actually did manage to make a frosted bulb, shocking everyone and making history.

via Wiki Commons

The truth is a little different from the story, but it's close enough. The fact is, we've been able to make frosted bulbs just as long as we've been able to make non-frosted bulbs, since frosted glass predates bulbs by many years. But the technique initially involved messing with the bulb's glass from the outside, which roughened the surface and attracted dust. GE assigned new engineers to frost a bulb from the inside—and this too was quite possible. But engineers who took on the project concluded that the resulting glass was so brittle that the company wouldn't be able to market it. When each engineer came to that conclusion, GE told them they'd passed the test. They were really testing the man's insight, not how good an inventor he was.

Then came Marvin Pipkin. He had no special insight about marketability. He just kept working on that bulb, assuming there had to be a solution. And he found one. A cleaning solution.

That's right: After treating the glass with acid, he added a cleaning solution to the inside of a bulb (we don't have the name of the relevant chemical, nor would it mean anything to us if we did). Then his phone rang, and he got up so quick, he knocked the bulb to the ground. Surprisingly, the bulb survived the fall intact. He'd stumbled onto the two-step acid treatment, a method for frosting glass that keeps the glass strong and also makes the light appear brighter.

If you have any of those frosted incandescent light bulbs in your home today, you have Marvin Pipkin to thank. Also, you really need to buy new bulbs. We have much better bulbs nowadays, c'mon.

A Security Tester Infiltrated A Bank In Beirut By Mistake

Let us set up for you the opening scene to an imaginary movie, an annoying and unrealistic fake-out the screenwriter is super proud of. We see a gang of thieves break into a bank. They're just about done with pulling off their heist when the cops show up and surround them. The lead robber slowly removes his mask. It turns out the cops know him—he's one of their own. This whole heist was really just a security op to test the bank's defenses.

Banks actually do order that sort of song and dance. They don't ask masked men with guns to pile sacks of gold into a getaway car, but they will invite a security expert to try to access a teller's computer, to test weak points in how the place runs. Often, the security expert doesn't reach the computer, and that's good. They aren't actually hoping to beat the system, just hoping to test the system. If they do succeed, they'll likely keep screwing around till they finally do get caught for something or another. Again, the goal here isn't a clean escape, it's to give the bank as thorough a check as possible.

Jayson Street, a sysadmin turned security expert, was hired to do one of these checks, by a bank in Lebanon. We don't have the name of the bank, or the date this happened, but we put our trust in National Geographic, who did a whole thing on this story. For convenience, let's call the bank First National. Street's job was to enter a branch of First National and plug a USB device into the teller's computer. Engineered correctly, this device could give allies remote control of the bank to approve all kinds of money transfers. For the test, he was using a dummy version that would prove he'd breached the system but do no real harm—it would just open up Notepad.

He felt a lot of internal pressure the morning of the test. Which is to say: He really needed to pee. So before the serious portion of his business, he rushed into the bank and headed for the restroom. Then he was relaxed again and ready to go. Armed with a lanyard and a vague badge, he claimed to be from Microsoft, there to update the computer equipment. An employee let him plug in his device—boom, network compromised. Then a second employee let him do the same thing to another computer.

believe them, because old people answer unknown numbers.

Finally, someone grew suspicious and brought in a supervisor. Street now opened his iPad to show off a forged email, ostensibly from the bank CFO giving Microsoft access to all the equipment. The bank had failed its test but still had a chance to pass the next stage by questioning his authority despite this fake email. Sure enough, the supervisor was unconvinced ... because the email was signed by the CFO of a different bank. No, Street hadn't messed up the forgery, the forgery was perfect. But the email was from First National, while he was instead currently in a branch of Bank of Beirut. Thrown off by those bladder pangs, he'd entered the wrong building and subsequently hacked the wrong bank.

He eventually managed to get the people who'd hired him on the line and convinced this bank that he wasn't a thief. But if he'd used a real hacking tool instead of his dummy device, he'd have robbed this bank without invitation ... and if he gave them an email with the right name on it, he might have got away with it too. We have to assume the compromised bank, having received a free threat assessment, updated its protocols. Maybe by taping signs to the bathroom door, reading: “For Bank of Beirut customers only.”

Soldiers Evaded Their Own Side, Thinking It Was A Game

In 2020, Lithuania lost five soldiers. They didn't lose the men in battle (though Lithuania had been supporting NATO efforts in Afghanistan with personnel for nearly 20 years). In fact, the men didn't die at all. Lithuania just lost them.

The Žemaitija Motorised Infantry Brigade were undertaking their graduation exam. Five men were supposed to show up at the exfiltration point at a scheduled time, but they didn't, and as the hours went by, their superiors started to worry. Even if the men hadn't been ambushed by enemy forces (say, those sneaky Belarussians), something surely had gone wrong. Maybe they were unable to find the way to the meeting point and had succumbed to the February wind.

via Wiki Commons

The military sent a helicopter to comb the area. Then they sent teams with dogs through the forest. Search parties worked for 24 hours without locating any trace of the men.

Then the men finally showed up. They'd got the time wrong for when the exercise ended, but they were otherwise perfectly fine. They'd noticed the helicopter and the dogs, sure, but they assumed those were part of the exercise, and so they hid themselves carefully to avoid being spotted. This was a scouting exercise, see. And stealth is an essential part of being a scout, right?

The Codebreaker Who Assumed It Was Normal To Break Codes

During World War II, spies waged a cryptographic battle, which is best remembered today for Alan Turing and the quest to crack the German Enigma machine ciphers. The head of ciphers and codes at Britain's Special Operations Executive branch was Leo Marks, whose career did not start very impressively. When he first joined the SOE, they gave him a codebreaking test that was supposed to take him just 20 minutes. It took him all day.

The reason it took him all day was SOE had neglected to give him the key. Without the key, this cipher was supposed to be totally uncrackable. Since he proved it to be quite crackable after all, Leo Marks discovered that he would have to introduce a few upgrades to British codemaking.

That might be the signature story from Leo's time in the service, and he had plenty of others. Like the following year, 1943, when Britain was receiving coded messages from Holland. Marks noticed something odd about them: They were all perfect. Meaning, they contained no errors whatsoever, and you could hardly expect the Dutch to code their missives without the occasional screw-up. But you know who you could count on to send codes without a single error? The Germans.

Hey, that's not us making a generalization, that was all Leo Marks. And so, he tested his belief. At the end of one of his replies, he added two initials, HH, which is a non-cipher code that means "Heil Hitler." Someone from Holland then replied to this message, adding an HH of their own. This supported his theory, which was eventually confirmed: The Dutch network had been compromised by Nazis.

After he won the war (with some assistance from the Allied armies), Leo Marks went on to become a writer. This is not typical. Most writers are not recovering from lives as spies, and if they are, they wouldn't admit it anyway.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.

Top image: Miramax Films