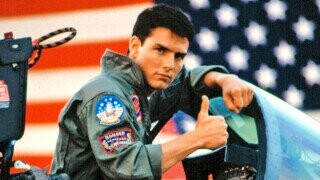

Why Tom Cruise Is Such An Effective Propaganda Tool

At times it can feel like everything is wrapped up in some kind of messaging. This week at Cracked, we're taking a closer look at propaganda and how it has shaped the world in ways that may not be so obvious.

Consummate movie star (and arch-enemy of couch cushions everywhere) Tom Cruise has had a long and varied career, playing a diverse array of roles ranging from a superspy in Mission: Impossible to a racecar driver in Days of Thunder to a vampire in Jerry Maguire. We don't tend to think of Cruise as a political actor necessarily, yet so many of his major career touchstones were unmistakably tethered to, often contradictory, political messages.

It's that moral incongruity that has allowed the legendary actor, who inarguably began his blockbuster career with a giant slab of sizzling military propaganda, to avoid being perceived as a figure of political note – even when his all-American movie star persona has repeatedly been utilized in a concerted effort to sway public opinion.

Don't Miss

Top Gun is a laughably unsubtle two-hour recruitment ad with an almost irresponsible ratio of beach volleyball to violent combat represented in the film. It's a bloodless fantasy in which the good-looking young white rebel gets to play with a bunch of kickass gear while occasionally battling a vague, nameless enemy, and of course, hooking up with his hot instructor to the sensuous sounds of '80s new wave band Berlin. It's the typical military experience in the same way Raiders of the Lost Ark is the typical middle-aged academic experience.

It's hard to imagine Top Gun was ever conceived of as anything but a glorified advertisement for the American military. To convince a reluctant Cruise to accept the role, all producer Jerry Bruckheimer had to do was show him, not the script, but the military toys that would be at his disposal throughout the shoot. They even hired director Tony Scott based on his ability to sell stuff specifically by making inanimate hunks of metal look sexy, as evidenced by his 1983 Saab commercial.

If it wasn't enough of a blatant propaganda piece in its conception, the deal the filmmakers struck with the military during production further tanked any of the film's lingering credibility, with consequences that continue to impact the film industry to this day. The Pentagon charged them "just $1.8 million for the use of its warplanes and aircraft carriers" but demanded script approval, requiring edits that would cast "the military in the most positive light." This included changing Goose's death from a mid-air collision to an ejector seat screw-up because "the Navy complained that too many pilots were crashing." This precedent led to an "unstated rule" in Hollywood that filmmakers required military cooperation in exchange for access to their expensive real-world props.

Famously, the Navy even set up recruitment stations outside theaters playing Top Gun and reportedly saw a "500% bump in enlistments" (and presumably a 500% bump in dudes creeping on their flight instructors). The film's popularity at the box office also bolstered President Reagan's military adventurism. Top Gun came out in the spring of 1986, just a month after U.S. airstrikes against Libya, which included targeting Muammar Gaddafi's residence, killing his "15-month-old adopted daughter" and "inadvertently" bombing several residential buildings, not to mention the French embassy, ultimately resulting in the deaths of 15 civilians. But after Top Gun hit theaters, "polls soon showed rising confidence in the military."

And there was no bigger fan of Top Gun than Reagan himself who, despite some "awkwardness" during the sex scenes, screened the movie for himself and Nancy at Camp David, later inviting Cruise over for a jellybean-eating session – which sounds like a euphemism, but isn't. Reagan, like many Americans, loved seeing their military portrayed as the "good guys" in a mainstream movie, which certainly hadn't happened at that scale since the Vietnam War.

Despite the fact that the real-life TOPGUN program was literally created during Vietnam in order to improve the Navy's "kill ratio," the subject is largely ignored by the movie. It could be argued, though, that Cruise's character Maverick is meant to be a stand-in for America itself; he doesn't always play by the rules, frequently makes mistakes, but he is ultimately both awesome and, most importantly, good. The underlying message is that America may have screwed up in the past, but it's still the lovable hero of the entire world, now cue the goddamn Kenny Loggins.

One guy who wasn't a fan? Oliver Stone. His unflinchingly violent, Academy Award-winning Vietnam War epic Platoon also came in 1986, and in many ways was the anti-Top Gun, which Stone publicly called a "fascist film." When Stone returned to the subject of Vietnam three years later with Born on the Fourth of July, who did he cast as real-life paraplegic Vietnam vet turned anti-war activist Ron Kovic? Friggin' Maverick himself, Tom Cruise (who incidentally was born on the third of July).

After Top Gun, Cruise had worked with screen legends Paul Newman and Dustin Hoffman (in The Color of Money and Rain Man, respectively) and was eager to follow in their footsteps and show off his dramatic leading man chops, eventually taking a pay cut to play Kovic. From Cruise's perspective, doing a political 180, from military puff piece to searing condemnation in just three years, was seemingly an artistically-motivated decision. But for Stone, casting the Top Gun guy was in and of itself an act of subversion intended to amplify the film's anti-war message. "I wanted to take his top-dog strength and turn it on its side, to flip it," Stone claimed at the time. "It's like Top Gun goes to war. You're number one, you're Mickey Mantle, but what happens when you get blown out of the cockpit?"

While nothing could ever rival Cruise's pendulum swing of the late '80s, some of his later movies may also represent more subtle attempts to shape certain American ideologies. Take the Mission: Impossible movies, for example. We've argued before that the entire franchise is an elaborate allegory for Scientology (for whom he is an even more active propagandist), but there may be a more obvious real-world comparison to be made.

The original Mission: Impossible TV show began as Cold War-era entertainment that glamorized and celebrated America's covert intelligence operations. Audiences loved the IMF specifically because they acted outside of normal governmental jurisdiction, engaging in expert acts of (often illegal) deception in an effort to best America's ill-defined foreign adversaries. Mission: Impossible repurposed America's troubling past (and present) by turning a CIA-like organization's shadowy exploits into easily-digestible weekly doses of adventure. And despite the show's penchant for fictional countries and unspecific threats, it wasn't immune from specific real-world allusions, hence the episode where Leonard Nimoy disguises himself as Che Guevera in order to thwart a planned Communist revolution, which is an absolutely ludicrous sentence to have to write.

Not entirely dissimilar from how Maverick's antics glossed over America's bloody military past, the first Mission: Impossible movie took the bold step of making the original series' Jim Phelps the villain of the story, metaphorically separating this new generation of IMF agents from the exploits of their predecessors, effectively serving as a low-key "interrogation of the American military-industrial complex in the wake of the Cold War."

Further yassifying America's intelligence agencies, several of the sequels concocted stories in which heinous acts historically perpetrated by the U.S. government were recontextualized as the modus operandi of Ethan Hunt's enemies. The villainous Apostles of Mission: Impossible - Fallout are responsible for a multitude of regime changes, with the purpose of installing puppet leaders, à la the CIA. And Mission: Impossible III literally begins with Ethan and his wife being tortured – which, seeing as it was the first Mission: Impossible movie in the post-9/11 era, may not have been a total coincidence.

Cruise's non-franchise early 2000s output wasn't wholly divorced from politics, either; most obviously, he co-starred in Robert Redford's Lions for Lambs playing a slimy Republican Senator trying to sell a journalist on America's "War on Terror." The fact that the star of Top Gun was playing the foil in a film critical of military propaganda didn't go wholly unnoticed at the time, either.

Most perplexing, in retrospect, though, was Steven Spielberg's 2005 blockbuster War of the Worlds. After tepidly supporting the U.S. invasion of Iraq while promoting Minority Report in 2002, Spielberg and Cruise made what seemed like an explicit manifestation of America's collective post-9/11 anxieties.

But despite the fact that it can clearly be read as a 9/11 parallel, in which an average American family led by a Yankees cap-clad patriarch are dislocated by a surprise foreign attack, in subsequent years, it's been interpreted as an allegory for the Iraq war, in which Cruise and his family secretly represent an Iraqi family. From this perspective, the alien invaders represent America, and Cruise's character only "saves the day … by essentially becoming a suicide bomber." And if War of the Worlds really was intended as a stealth critique of U.S. foreign policy, that would be in keeping with its source material; the original H.G. Wells novel was meant to be a "critique of imperialism" which was even made very explicit in the text when Wells compared the Martian invasion to "colonial expansion in Tasmania."

Now, Cruise's career has seemingly come full circle with the upcoming sequel Top Gun: Maverick, which, like the original, struck a mutually-beneficial deal with the military. Again leading to both the movie and the armed forces are being sold in tandem thanks to tie-in promotions such as a Top Gun "Challenge" on The Bachelorette, which, in the ultimate ball drop, was not a beach volleyball contest.

Ultimately Tom Cruise makes for such an effective propaganda tool because he is an embodiment of America, not just in some kind of regressive 1980s ideal of the all-American male, but in the sense that his politically antithetical career choices inadvertently reflect the country's consistently fraught, wildly indefinable moral center. Not so much in The Mummy, though.

You (yes, you) should follow JM on Twitter!

Top Image: Paramount Pictures