Ernie Kovacs Was the Secret Father of Counterculture Comedy

When young Chevy Chase beat out all the comics from The Carol Burnett Show for a Best Supporting Actor Emmy after Saturday Night Live’s first season, he thanked all the usual suspects, namely his fellow Not Ready for Primetime Players and Lorne Michaels for giving him the job. Less expected was a tribute to a comic voice from television’s past. “And I also would like to thank Ernie Kovacs,” Chase said. “I swear.”

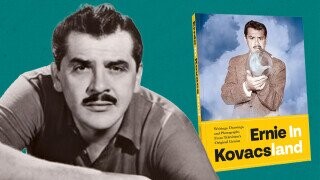

But Chase’s shout-out wasn’t all that surprising, according to Josh Mills, author/editor of the upcoming book Ernie in Kovacsland: Writings, Drawings, and Photographs from Television's Original Genius. (Mills is the son of Edie Adams, Kovacs’ wife and co-star on his many 1950s comedy shows.) After all, Kovacs had a direct influence on the lunatics at National Lampoon, the original writing staff of SNL, Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam and late-night revolutionaries like David Letterman. “You know, the ‘throwing the pencil at the camera,’ all those things are Ernie,” Mills tells me. “He did that in 1954.”

The direct line from the visually inventive Kovacs to the next generation of comedians goes straight to It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, where a tilted camera might cause Shandling to slide out of frame. Beyond playing with the fourth wall and other visual devices, Shandling was inspired by Kovacs’ chill delivery. ”Ernie is the most comfortable and casual,” Mills explains. “There’s no pressure if you watch him on his show. If the gag goes wrong, it goes wrong. Who cares? We keep moving on, we make a joke. Gary Shandling was trying to channel that kind of energy.”

Don't Miss

In a burst of creative frenzy that lasted a little more than a decade, Kovacs not only created the visual language of television comedy but wrote like a madman as well: newspaper columns, funny articles for men’s magazines, Mad cartoons, poems and novels. Mills inherited the massive Kovacs archives from Edie Adams and Ernie in Kovacsland is the result — a curated volume of hilarious Kovacs’ creations alongside essays about the comedian and his influence.

Below is an exclusive excerpt from the book that explains Kovacs’ connection to current comedy, courtesy of cultural historian Pat Thomas.

* * * * *

Josh Mills and I were sitting with Jerry Casale of Devo discussing Ernie Kovacs’ influence on the New Wave performance art mavericks when it occurred to me that Kovacs was like Jimi Hendrix — his professional career was short, but his influence was wide and lasting. Casale quickly agreed.

Later, I was visiting with political satirist (and co-founder of The Yippies) Paul Krassner when I mentioned Kovacs to him. He fondly lit up hearing that name, contrasting Ernie against today’s obnoxious late-night TV comedians who scream for effect and don’t write much of their own material. Or as he said, “Kovacs’ show was never the same twice,” going on to make the point that today’s shows always follow a format (such as an opening monologue that must happen each evening). “Ernie was relaxed,” Krassner continued, “never shrieking, and he wrote all of his own skits and jokes. I liked his easygoing approach that didn’t need a bunch of writers and producers to bring it to fruition.”

While youngsters like David Letterman and Jay Leno were paying attention to Kovacs’ M.O., they sadly overlooked the subtle persona of his delivery. But they borrowed at least one of his (and Tonight Show host Steve Allen’s) ideas — go to the street with a camera and interview average joes walking by. That skit (no matter who does it) never fails to get a laugh.

As Edie Adams pointed out in her 1990 memoir, Sing a Pretty Song, “Letterman’s head writer, Steve O’Donnell, and his staff spent three months ... studying Kovacs kinescopes, so I know they’re fans.” She also wrote, “Alan Zweibel, a former writer on Saturday Night Live, said that all the writers on that show ‘had Kovacs at the core of everything we did. Whenever there was a question, we said, ‘What would Ernie have done?’”

Zweibel continued, noting Kovacs’ interest in “the distortion of pictures and sound.” Edie solidified the SNL influence when she noted that when that group of “Not Ready for Prime Time Players” won their first Emmy, “Chevy Chase grabbed the mike and said a special thank you to Ernie Kovacs. I’ll never forget him for it.”

While I was watching an old Ernie TV episode with vintage pop-culture fan Kristin Leuschner, she pointed out how Kovacs pushed the boundaries of simple camera angles — Kovacs made the audience POV part of the eye-popping fun, be it putting his face right up into the lens or pulling way back to allow a different or a wide view not normally done in those early days of television.

And while Kovacs was a popular late 1950s/early 1960s phenomenon, he posthumously inspired the late 1960s counterculture. As writer Martin McClellan pointed out in The Seattle Review of Books, “Laugh-In (took some) visual tricks straight out of Ernie Kovacs’ playbook ... fast zooms in on dancing girls, guitar-based twangy upbeat music, prop walls that opened and slid to reveal actors and comics delivering sharp one-liners.”

Kovacs — along with Lenny Bruce, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Mad magazine and others — fueled Krassner and his fellow Yippies Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. Jerry and Abbie revolutionized political activism in the 1960s. The stunts they pulled are infamous. They shut down the New York Stock Exchange by dropping dollar bills onto the floor, which traders fought over, and they turned a march on Washington into a psychedelic happening at the Pentagon in October 1967. When Jerry was federally indicted as part of the Chicago 8 (later the Chicago 7) — for “the whole world is watching” riots that took place during the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention, he described that moment as winning “the Academy Award of protest.” Kovacs’ comedy was apolitical, but his style helped inspire a later generation of leaders that led young people against the bogus Vietnam War.

Journalist Jack Newfield, in The New York Times, December 29, 1968, wrote, “Abbie Hoffman is a charming combination of Ernie Kovacs, Artaud and Prince Kropotkin. He is a put-on artist, an acid head (over 70 trips), a mass-media guerrilla...” In Hoffman’s own 1968 tome, Revolution for the Hell of It, he interviewed himself: Can you think of any people in theater that influence you? “W.C. Fields, Ernie Kovacs, Che Guevara, Antonin Artaud, Alfred Hitchcock, Lenny Bruce, the Marx Brothers.”

1960s underground cartoonist Skip Williamson — described by The New York Times in a 2017 obituary as “a rambunctious creator of underground comics that merged his radical politics with his love of scatological humor” (the Times included a Williamson drawing of Jerry Rubin) — was another Kovacs devotee. In a March 2017 ComicMix article, editor/commentator Mike Gold wrote, “Skip’s most revered character was Snappy Sammy Smoot, a hippie take on Ernie Kovacs’ popular character Percy Dovetonsils, only — and incredibly — even more surreal.”

In fact, Kovacs was a contributor to Mad. The magazine’s founder Harvey Kurtzman enjoyed a mutual admiration relationship with Kovacs, and Ernie’s own humor would pop up in various issues. Kovacs even wrote the introduction to the 1958 Mad anthology paperback, Mad for Keeps.

Arguably, early Kovacs musical skits cut a path for some of the surreal MTV videos produced by the likes of the Cars — check out the Cars’ “You Might Think” for an example of Ernie’s visual influence. As one Kovacs biographer pointed out, “the love-stricken singer turning into a fly and buzzing toward his beloved’s nose is practically a mini-homage to Ernie’s 1950 camera tricks.”

Speaking of pop music, let’s not forget Harry Nilsson’s Kovacs-inspired moment — during a 1972 BBC TV live performance, Harry visually mimics Ernie’s “Nairobi Trio” while singing his own song “Coconut” in a gorilla suit. Frankly, the wacky repetitive lyrics are a Kovacs pastiche as well.

I was drafted by Josh Mills to work on this collection of Kovacs material after the publication of my book that gathered up some of Yippie Jerry Rubin’s ephemera — and while I worked on this Ernie book, I concurrently assembled a similar collection of writings, drawings and photographs from Allen Ginsberg’s personal archive. Halfway through the Kovacs/Ginsberg process (with the Chicago 8’s theatrics in the back of my mind), I began to realize that a counterculture thread connected them.

I was too young to have lived the 1960s hippie journey as it was happening, but I felt validated by a book review penned by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat. (I confess I haven’t read the memoir written by Wes “Scoop” Nisker, which they describe as “recommended for those who are nostalgic for the wild experimentation of the 1960s and the ardent idealism of youth and would like to have a jaunty trip down memory lane.”) But since Nisker lived during the era I’m attempting to encapsulate in this essay, this is what caught my eye: “Born December 22, 1942, in Nebraska ... Nisker says that his first guru was Alfred E. Neuman of Mad magazine. He felt connected to the youth culture that came alive in the 1950s with rebel James Dean on the screen and rock-and-roll on the radio. The author lionized Beat poets and writers — Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg. Nisker also fed his discontent with the status quo with the sarcasm of his favorite comedians — Sid Caesar, Ernie Kovacs, Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl.”

Lastly, I recently discovered that the first-ever biography of Ernie, Nothing in Moderation, was written in 1975 by David Walley. I wasn’t familiar with Walley, but I noted his previous book was a biography of Frank Zappa. In a 2020 Zappa documentary titled Zappa, there’s a vintage clip of Zappa praising Ernie for inspiring his own “lifelong pursuit of utilizing the ordinary for a unique musical approach.”

The director of the Zappa film, Alex Winter, told Variety in November 2020, “And the thing that I liked about Zappa’s humor was that it was not often the humor that he put into his records. The way he used humor in his records was almost like another musical instrument. The way, say, Ernie Kovacs would use it...”

I rest my case.

(Ernie in Kovacsland: Writings, Drawings, and Photographs from Television's Original Genius, out July 25, is available for preorder. Order through this link to also receive a free copy of Edie Adams’ autobiography, Sing a Pretty Song.)