5 Phrases No One Would Use If They Knew Where They Came From

We once told you that the famous quote about learning who rules over you by finding out who you’re not allowed to criticize actually originated in 1993 from a white supremacist sex criminal. And we revealed that "the definition of insanity is doing the same thing and expecting a different result” came not from Einstein but from Narcotics Anonymous and from a mystery novel about women’s tennis.

With the following phrases, you don’t need to have any idea where they came from to use them. But once you do know, ouch, you’ll never think of them the same way again.

‘Yelling Fire in A Crowded Theater’ Comes from A Terrible Court Decision

When people say they’re being silenced, their opponents quickly point out that freedom of speech isn’t absolute (these same opponents, when their own side is silenced, will call this censorship deeply discriminatory and unfair). For example, they note you can’t yell “fire” in a crowded theater. The logic here is that the First Amendment has some exceptions, so this latest thing might fall under that exception, maybe.

The law does recognize many exceptions to the First Amendment, and some of these are bad exceptions, because some standards are bad. Falsely shouting “fire” (aka the “clear and present danger” standard) happens not to be an exception. It used to be, a century ago, but then the Supreme Court changed that standard in 1969 because it was a bad standard.

The standard, and the phrase, comes from the 1919 case Schenck v. United States. We mentioned this case in passing recently when talking about an actual fire in a crowded theater — in Schenck, the court upheld the conviction of two war protesters, Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer, who were imprisoned for distributing leaflets criticizing the draft.

In reality, Schenck and Baer were ahead of their time. America hasn’t drafted anyone since Nixon ended the practice (he ended it while the Vietnam War was still in progress, by the way), and no one gets locked up for dodging the modern counterpart — selective service. But the official U.S. position in 1919 was that the draft was legal and good. The Supreme Court had ruled on its constitutionality the previous year. Still, the idea that someone should be imprisoned for arguing otherwise, and for implying — not even stating — that men should dodge the draft, is nuts, right? And yet that’s what you’re citing when you say “you can’t yell fire in a crowded theater” because the phrase came from that court decision.

Oh wait, crap, we just accidentally quoted Dred Scott v Sandford.

“Hold on, I wasn’t talking about jailing World War I socialists,” you might say. “I was talking about clear and present danger in general. Or about theaters in general, and ones showing The Rock’s movies in particular.” But when you lay out a standard giving authorities power, you have to consider the worst way they can use it. The 1969 case overruling Schenck, Brandenburg v. Ohio, covered criminals much less sympathetic than Schenck and Baer — it was about Klansmen — but the court now correctly ruled against limiting speech partly because of whom else the government might silence given the chance.

When it comes to the “crowded theater” argument, you don’t even have to speculate on how the government might possibly misuse that standard. The actual decision that originated that argument was already bad. It was so bad that the judge who wrote that phrase, Oliver Wendell Holmes, changed his mind about speech protections in less than a year.

The current First Amendment standard instead just criminalizes speech that incites imminent lawlessness. The speech must provoke lawbreaking, not just unspecified bad stuff, and it has to provoke it right now. You are allowed to advocate for people to break a law, and this is how many bad laws get changed. But if, for example, you tell a crowd to riot, and they immediately riot, you might be liable for that.

You might be thinking that I’m talking about Trump and January 6th, and that I picked that example just to target him. But that’s not necessarily the case, it’s simply been the textbook example for decades. And speaking of that whole Trump thing...

‘Vox Populi’ Is Really About Why the Majority Voice Shouldn’t Win

“Vox populi, vox Dei,” posted Elon Musk recently, when a poll told him to bring back Trump’s Twitter account. The Latin phrase translates as “The voice of the people is the voice of God.” When the people speak, you must pay heed, because their word is law.

The earliest recorded use of “vox populi, vox Dei” is actually a letter from the year 798 that says listening blindly to the majority view is a bad idea. “And those people should not be listened to who keep saying the voice of the people is the voice of God,” wrote the scholar Alcuin of York, “since the riotousness of the crowd is always very close to madness.”

Once you’ve heard the quote in context, it no longer makes sense in your mind as an unironic phrase. You can say, “People have a right to decide stuff,” or “There’s wisdom in crowds,” but call people’s views the voice of God, and now, you’ve gotta be making fun of the idea. It’s the difference between saying, “Mother knows best,” and saying, “You gotta obey Mom, her word comes down from on high.” Or it’s like how a man probably knows better than to call himself “God’s gift to women” — we’d only use that phrase to say someone thinks they’re God’s gift, because no one can be.

Of course, Twitter polls don’t even reflect the voice of the people; they are easily manipulated, by bots and other insincere actors. Also, Musk doesn’t really think he’s bound by public demand. We can assume he’d already decided what course to take before making that poll. Much like when he asked Twitter to decide whether he should sell $5 billion in Tesla stock, when he’d secretly already arranged the sale weeks earlier.

Oh, and speaking of lying hucksters ...

Snake Oil Is Actually Effective, Hence the Phrase

When someone claims he can solve traffic using single-lane tunnels, or says you’ll double your money by buying Shiba Inu coins, you might say they’re slinging snake oil. That’s highly insulting — to snake oil.

Snake oil really is good for you, you see. The oil, extracted from snakes’ fat sacks, contains eicosapentaenoic acid, something we know is good for you when we get it from fish and that we can get in higher concentrations from water snakes. Along with all kinds of assorted potential benefits, including brain stuff, it traditionally had an easily observed effect on joint pain.

Now, these benefits weren’t some surprise we discovered in the lab years after snake oil salesmen were a thing. People already heard about snake oil’s curative properties back in the Old West, which was why peddlers advertised the stuff. These salesmen weren’t quacks because they sold snake oil. They were quacks because they didn’t sell snake oil.

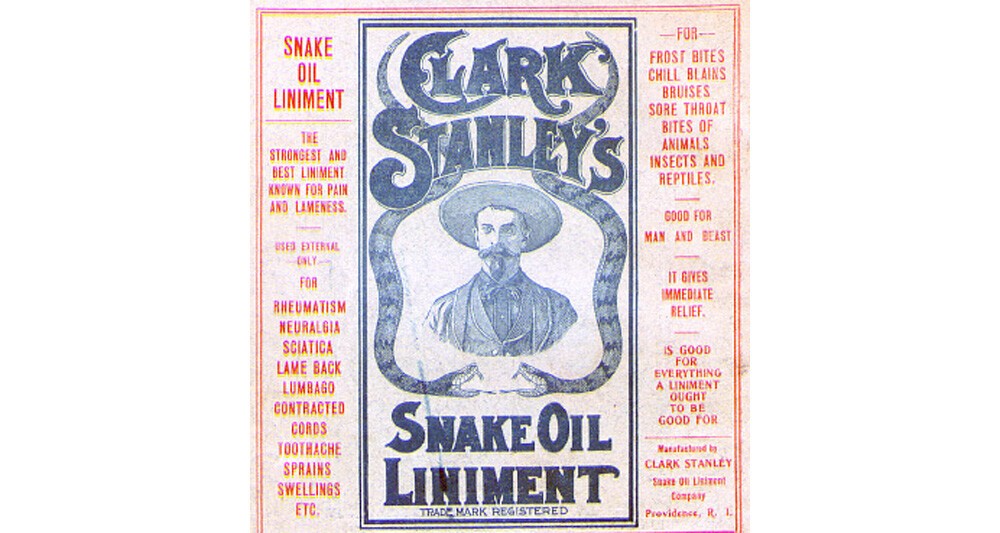

Admittedly, that needs some explanation. “Snake oil salesman” became a taunt rather than a simple description because of Clark Stanley, who packaged and distributed “Stanley’s Snake Oil Linament” at the turn of the 20th century. Stanley held flashy demos where he’d pull a rattlesnake out of a sack, cut it open in front of a crowd, drop it in boiling water, then skim the fat right off the top of the stew so people could sample it.

“Is good for everything a liniment ought to be good for.”

Stanley’s Snake Oil Linament didn’t do much of anything, fulfilling none of his more outlandish claims and not even treating the stuff snake oil should treat, like rheumatism. In 1917, the Department of Agriculture analyzed the product and found it contained no snake oil at all. It contained some mineral oil, and assorted other nonsense like pepper, but despite the flashy demos, the packaged liniment contained no snake oil. Even the snakes he publicly slaughtered were the wrong type, but the main issue was his wares contained no essence of snake whatever. Snake oil was legit, but the snake oil salesman was not.

Calling someone a snake oil salesman, after Stanley, should be like saying someone’s trying to sell you the Brooklyn Bridge, after the con artist who did that. But dropping the “salesman” part of the phrase and calling their worthless wares snake oil, well, that’s like calling their wares the Brooklyn Bridge, which doesn’t make much sense at all.

The Guy Who Coined the Term ‘Racism’ Had Some Strange Ideas About Race

Racism may have always existed. People were even racist in some Star Wars stories, and those happened a long time ago. But before 1902, if people had a word for the concept, it was “racialism.” The first person to call it “racism” was an army officer, Richard Henry Pratt.

To be clear, we don’t seriously think anything you learn about Brigadier General Pratt should convince you to stop using the word “racism.” It’s an established word. But you might still be interested and surprised to learn Pratt’s ideas on the subject. He opposed segregation (good). He wanted to avert (good) a predicted total elimination of all Native Americans within a few generations. He did this by setting up a boarding school (good?) for Native kids at an abandoned military post. This school and its imitators sought to stamp out all Native American cultures, forbidding children from speaking their native languages and beating them when they disobeyed (uh, not good).

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” said Pratt. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: That all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” That was from a speech where he spoke against racism.

You’d hope there were a better solution to “The Indian Problem” than to beat the race out of them. Still, spare the rod, spoil the child, right? Which, one last time, speaking of…

‘Spare the Rod, Spoil the Child’ Comes from A 1600s Sex Poem

“Spare the rod” comes from the Bible. The Book of Proverbs tells us, “He that spares his rod hates his son; But he that loves him chastens him.” For the full line “spare the rod, spoil the child,” however, you have to look to a paraphrasing of the original proverb, which we got from a 17th-century poem called “Hudibras” by Samuel Butler:

What med’cine else can cure the fits

Of lovers when they lose their wits?

Love is a boy by poets styled;

Then spare the rod and spoil the child.

Some people, on hearing this origin, still think that’s a source for child-rearing advice. But these lines aren’t talking about parents and kids. They’re talking about lovers. The context is a knight is trapped, and a widow says she’ll release him, but only if he’ll agree to an idea of hers — whipping.

With comely movement, and by art,

Raise passion in a lady’s heart?

It is an easier way to make

Love by, than that which many take.

Who would not rather suffer whipping,

Than swallow toasts of bits of ribbon?

Is she just talking about this man flagellating himself penitently, as annotated copies of this poem from centuries later claim? Uh, we doubt that. Sexual sadism goes back a long time (even farther back than racism, which was invented in 1902).

Did not th’ illustrious Bassa make

Himself a slave for Misse’s sake?

And with bull’s pizzle, for her love,

Was taw ’d as gentle as a glove?

A pizzle, in case you don’t know, is a penis. A bullwhip was traditionally made from the skin of a bull’s penis, but still: We’d say calling it a penis instead of a whip is a fairly definitive way of saying that this poem has sex on its minds.

Did not a certain lady whip

Of late her husband’s own Lordship?

And though a grandee of the House,

Claw’d him with fundamental blows

Ty’d him stark naked to a bed-post,

And firk’d his hide, as if sh’ had rid post

“Be my sub” is the explicit sexual meaning here, and there may be other layers as well (“the rod” could mean his penis). So any parents thinking of quoting “spare the rod, and spoil the child” should realize they’re basing their relationship with their child on a 1600s poem about BDSM.

And also, we guess, they should avoid beating their children because that’s actually bad for children, but you knew that already, right?

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.