A Short History Of 'Calvin and Hobbes,' The Last Great Newspaper Comic

This might be a weird question, but have you ever thought about snowmen as existential body horror? Let’s try another one: have you ever wanted a treehouse where just you and your best friends could hang out and wear cool hats and fly pirate flags? How about this one: have you ever wanted to be best friends with a tiger?

If you answered “yes” to all three, congrats! You and I have a lot in common. We’ll get along just fine these next five days. And right up front, yes, that treehouse club is called Get Rid Of Slimy girlS, but women are welcome here. We’re more grown up and enlightened now, we just haven’t figured out a better acronym than G.R.O.S.S. yet.

Don't Miss

If those two paragraphs both confused the hell out of and intrigued you, then sit back and grab a Treat Yourself Beverage Of Choice, because we’re about to talk all things Calvin and Hobbes. Or at least as much as we have time for. There’s a lot in Calvin and Hobbes. Hopefully, you’ll leave this weeklong column series wanting to spend more time with a six-year-old and his tiger — right after I explain why that sentence isn’t creepy.

Quick question: what’s a newspaper?

Think the internet, but finite and fewer (not zero!) Nazis. Think Twitter, but rolled up into a paper cylinder and thrown at your front door. Think a zine, if your art collective friends somehow got a sit-down meeting with the President. Think a newsletter, but for the entire city of Trenton, New Jersey, written by maniacs.

Billion Photos/Shutterstock

Yes, you kids with your tablets and smartphones will never know the magic of receiving literally all the information you’re gonna get for daily life via a fish-and-chips wrapper. But fist-shaking at whippersnappers aside, there is something interesting about the newspaper that I think has been lost in the age of the internet: sections. A paper comes with news—presumably reported and fact-checked—sports, business, arts, and whatever else the editors decide to throw in. You take in all the information you need for the day over breakfast or on your commute, and once you’ve swallowed enough news to be a responsible citizen and enough sports to be conversant with Chet and Brad at the water cooler, you get a little treat with the funny pages.

Most major cities have one or two papers, but back in the early 20th century, cities could have up to six papers competing for readers. That’s two more street urchins yelling “Extry! Extry!” than most intersections have corners. A big selling point for the papers was their comics. Papers would dangle the superior quality of their cartoons to readers, like if the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times had split the city along Snoopy v. Garfield battlelines. Eventually, papers consolidated, and comic syndicates came along—basically collectives of comics artists within a corporate structure who could sell their strips to multiple papers to get a wider audience.

Comics were selling points? What’s so great about newspaper comics? Are comics funny?

The answers are “yes,” “some things,” and “sometimes.” By the daily nature of their existence, you’re not getting a cartoonists’ perfect game every single outing. Sometimes, Jim Davis hates Mondays, so Garfield hates Mondays. Sometimes that happens every Monday for longer than anyone reading this has been alive. Comics are often comfort food. Sure, an A+ comic can make you laugh out loud or think differently, but most of the time, reading a comic is like checking in with old friends. It’s a quick, low-stakes read that just might make you chuckle before you grab your briefcase and slough off to the cubicle factory or wherever it is real adults work.

Random House

Comics don’t have to be funny, either. Newspapers used to be stuffed with adventure comics like Flash Gordon or soap operas like Mary Worth. A fun thing to keep in mind is that Mickey Mouse cartoons used to open serious movies, and newspaper comics are 50-60 years before TV, meaning adults have always loved animated entertainment. Watching the old ladies of Mary Worth cry in their gardens or whatever (I uh, didn’t read a lot of Mary Worth. Neither did the Pearls Before Swine guy) was totally normal daily reading for our grandparents.

When I was a kid, my parents got two papers: The Tennessean (Nashville’s daily) and The Daily News Journal (the daily for Murfreesboro, the suburb we lived in). My opinions of the two papers was strongly based on what comics they carried, so I guess the street urchin battles of the early 20th century carried on to the mind of an elementary school-aged millennial.

What is Calvin and Hobbes?

Well, none other than the authoritative voice of Slate calls Calvin and Hobbes “the last great newspaper comic,” which is both true and silly. The article even points out Frazz, The Boondocks, and Doonesbury, all of which are great comics that came after or (in the case of Doonesbury) outlasted C&H. But thanks to the newspaper industry dying and an expansion of how people get comics, the monocultural impact a daily strip can have is smaller than the heyday of Peanuts and Garfield. C&H was the last standout strip before the internet gave us things like xkcd or Cyanide and Happiness.

What’s Calvin and Hobbes about? Boy, I cannot tell you how much I wish my entire knowledge of this strip was Eternal Sunshine-d completely out of my mind so I could read this sentence for the first time: a six-year-old boy and his stuffed tiger, whom he imagines to be living and breathing and talking, have adventures navigating daily suburban life and its endless curiosities, and sometimes they clone each other or shoot space fighter jet lasers at dinosaurs.

Andrew McMeel Publishing

Calvin and Hobbes is one part troublemaker kid exploring, one part wild fantasy, one part philosophical musings, one part saccharine family wholesomeness, all stirred into a giant stock pot with breathtaking art as its broth and ladled out into four-panel bowls for a more flavorful stew than this tortured metaphor is conjuring. Despite a modestly sized cast of characters (parents, teacher Miss Wormwood, classmate Susie, bully Moe, and babysitter Rosalyn are basically it) and meat-and-potatoes settings like home/school/outside, the world of Calvin and Hobbes is limitless. Seriously, the Wikipedia page for “secondary characters” features “living food and aliens.” Oh, and the jokes are funny, too. Comedy generally ages like milk, but there's a timelessness to C&H unmatched by few other comics.

Sounds rad! Why isn’t it still around? Did the artist die or something?

*checks Google, keeps fingers crossed entire time between turning in draft and publication* Not as of this writing! After 10 years, creator Bill Watterson walked away from the noble trade of newspapermanning, ending Calvin’s permanent placement in first grade and presumably sending Hobbes to some sort of tuna fish sandwich-covered netherrealm. For comparison’s sake, Charles Schulz created Peanuts in 1950 and is still publishing today despite dying in 2000.

We’ll get into this more with the next article, but Bill Watterson wanted out of the newspaper business and didn’t want to sell or license the rights to his work in any way. No animated TV feature, no blockbuster movie, no multimillion-dollar merchandising deals. Hobbes’s voice will always be the voice Calvin imagines in his head for Hobbes and Calvin’s voice will always be the voice you imagine in your head for Calvin. We’re never getting any celebrity voices attached to the Crisco-haired kid and his jungle cat, no matter how many times I lobby the federal government to mandate production of a 90-minute feature starring a reunited Desus and Mero. Bill Watterson wanted his creation to stand alone as a finite strip, and here it is. You can buy a single volume collection and rest assured that it’s the collection. Watterson’s a fascinating person in his own right, but like I said, we’ll get to him in the next article.

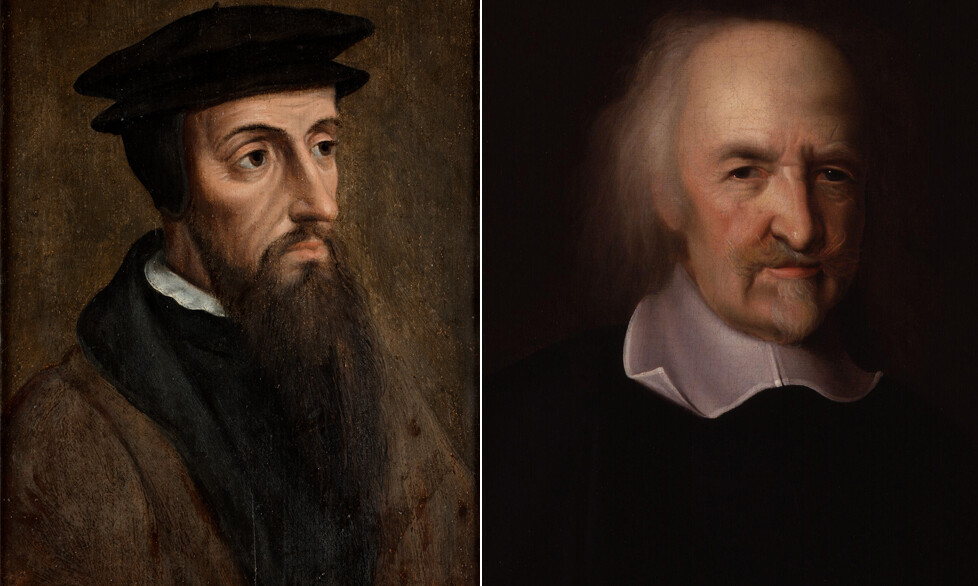

Why are they named Calvin and Hobbes?

Lastly, I guess we should ask why these names. Calvin, inspired by Protestant Reformist John Calvin, and Hobbes, inspired by social philosopher Thomas Hobbes. For some reason. “An in-joke for poli-sci majors,” Watterson says. Calvin does address his namesake’s penchant for predestination and Hobbes doesn’t hold humans in too high a regard, but it seems like that’s about it, characterwise. While Calvin and Hobbes wax philosophical to each other, I’d have to be a very specific type of nerd to try to Pepe Silvia my way to a unified theory of Calvin and Hobbes having Calvin and Hobbes more directly embody John Calvin and Thomas Hobbes.

Mostly, I think Watterson likes putting his own little quirks and interests into the world of the comic. He was writing dinosaurs as characters years before Jurassic Park shattered the box office. Hobbes started as Watterson drawing his cat, Sprite. No six-year-old possesses the knowledge of fine art that Calvin does. If the strip is about Calvin permanently struggling to be himself, it certainly allows Watterson to fully be himself. Which is a pretty weird guy, in a good way -- tune in tomorrow!

Chris Corlew is a writer and musician living in Chicago with a child who has Calvin tendencies and a cat too fat to be Hobbes. He co-hosts The Line Break podcast and is one-half of b and the shipwrecked sailor. Send him Calvin and Hobbes strips on Twitter.

Top image: Andrew McMeel Publishing