In The 1970s, A Bestseller Claimed The Planets Would Align And Destroy Everything

Welcome to Oofageddon! or Cracked's deep dive into the colorful world of half-baked Ragnaroks. Check out our previous installments on the 64-year-old woman who claimed she was giving birth to the messiah, prophecies of the 1800s, Halley's Comet, and alien intervention during the Cold War.

If you’ve learned one thing from Oofageddon! it’s that you should buy my new book. But if you’ve learned two things from Oofageddon!, your second insight should be that apocalyptic fervor can be whipped up by anyone. Religious zealots, respected scientists, and random nobodies can all prophesize doom… and they made doomsaying so popular that now it’s just another part of our day.

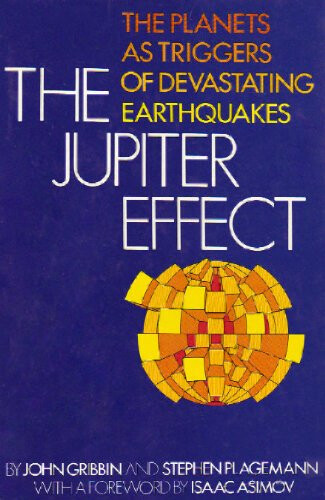

In 1974, The Jupiter Effect hit bookstores. Its two writers were respected astrophysicists John Gribbin and Stephen Plagemann, and it featured a foreword from none other than Isaac Asimov. Its premise was simple: in 1982 the planets would align, producing tidal forces so powerful that the San Andreas Faultline would suffer an earthquake of Dwayne Johnsonian proportions, among other potential natural disasters. It was a bestseller.

Don't Miss

For a book about how millions of people could be killed and society as we know it thrust into chaos, The Jupiter Effect is dry and technical. That was probably its appeal, the detailed bibliography and dull language from two notable smarty-pants giving it a patina of credibility. This was also a time when our knowledge of earthquakes was still relatively weak -- the book’s preface says it was written “as the new theory of plate tectonics has grown up” -- so it’s not shocking that people came away from this a little worried. Or a lot worried.

Walker & Co. Publishing

That doesn’t mean it was anything other than gibberish. The argument was that the planets would line up in a way that they, especially the dense Saturn and Jupiter, would exert unusually strong tidal forces on the sun. That would increase sunspot activity, those sunspots would bombard the Earth with high-speed particles, and the Earth’s atmosphere would be disturbed to the point where our rotation altered. The end result would be earthquakes galore.

Seismologist Charles Richter -- yes, that Richter -- called the book “pure astrology in disguise” and “very close to pure fantasy.” This was a theory so bad that even the Institute for Creation Research, which argues that the Earth is only a few thousand years old, ripped it apart. While the planets did get unusually close, they weren’t going to “align” like they were taking a family photo, and even if they did the gravitational impact would have been negligible.

This didn’t prevent some overreactions. Griffith Observatory fielded reams of worried phone calls, while a Denver planetarium said people called to ask if they should sell their homes and move to a less seismically volatile city. And The Jupiter Effect was big enough to go international: Chinese newspapers told readers not to worry, while some of India’s more sensationalist papers warned of riots, disease, and quakes. One paper claimed that a small religious group in the Philippines tested out padded living quarters and suits.

Nothing happened, of course. The planets were closer than they’d been since 1803 and until they’re slated to meet again in 2357, but on Earth the biggest impact was that planetariums got an excuse to throw tongue-in-cheek parties. Media coverage was critical of the theory, but boy was it covered.

If you’ve read the rest of Oofageddon!, you’ll know that such reactions are old hat. But while most people went about their lives, dramatic, pseudo-technical “we’re all screwed!” books had officially become an acceptable part of the mainstream media landscape. Previous apocalypses, for all the attention they received, were limited to prominent newspapers quoting wingnuts, and said wingnuts building an insular community of believers. The Jupiter Effect became its own little media empire.

A few months before catastrophe was supposed to strike, Gribbin retracted his core assertions. That didn’t stop him from penning both 1982’s The Jupiter Effect Reconsidered, which argued that his prediction had actually unfolded in 1980 and triggered the eruption of Mount St. Helens, and 1983’s Beyond the Jupiter Effect, which tried to put an analytical bow on the whole affair. Also in 1982, a film called The Jupiter Menace piggybacked off the earthquake prediction by adding Biblical prophecy to declare that the world would end in 2000. George Kennedy narrated, for some reason.

The Jupiter Effect wasn’t the only apocalyptic book to inspire a movie. Hal Lindsay’s 1970 book The Late Great Planet Earth used fringe eschatology to predict imminent famines, earthquakes, a Soviet invasion of Israel, and other disasters as Christ’s return drew near. First sold in Christian bookstores and through the mail, it eventually moved 35 million copies and was declared the bestselling nonfiction book of the 1970s by The New York Times. Its 1977 film, narrated by Orson Welles at his least discerning, interviewed everyone ranging from a witch and an astronomer to a computer security expert to the academic authors of scary books like The Population Bomb, Famine 1975! and, uh, The Jupiter Effect. Please enjoy this hilariously ominous trailer:

We’ve looked at both religious and secular doomsayers, but the 1970s was when they converged and fueled each other. There was a thirst for doom. It was a nervous decade: the Cold War was tense, environmentalists were sounding alarms, serial killers were rampant. Lindsay’s book told people not to trust the church, Gribbin’s implied all the other scientists were wrong, and they had all the media tools they needed to get attention.

If you don’t trust the institutions of the day, you’ll latch onto something -- anything -- without really worrying if its finer theological and scientific arguments hold up. Perhaps not coincidentally, one of the funniest and most prescient responses to The Jupiter Effect came from a 1982 column in The Oklahoman, which noted that doomsday prophesying “has been crowded by so many amateurs that a legitimate seer is hard to recognize.” Oklahoma City’s planetarium got over a hundred phone calls about the alignment, like they’d heard yet another story of doom and gloom and thought “Crap, do I have to worry about this too?”

Hal Lindsey is still kicking today, and he was preaching our imminent end into his golden years with 2003’s Faith for Earth's Final Hour. John Gribbin is still around too, and being stupendously wrong about the planets conspiring to rip Earth apart didn’t hurt an otherwise stellar and varied career. It’s fitting that they’re both still with us, because today we’re living in the aftermath of the media environment they helped create.

By the 1970s anyone with a gripping vision of doom could get a book printed or a movie made. Maybe you took it seriously, or maybe it just added to the wave of despair that seemed to be gripping the country. It was a culmination of fearmongering becoming easier and easier for centuries, and a preview of the deluge of scary crap you can find on social media and YouTube today, except now the bar to get attention is lower still.

The world’s going to end someday, but only a long time after you do. So while there’s plenty of bad news out there, the next time you hear that the apocalypse is right around the corner just remember that the doomsayers have been proven wrong time, and time, and time again. Oh, and buy my book.

Mark is on Twitter and has a brand new collection of short stories.

Top image: urikyo33/Pixabay

You can check out further installments of Oofageddon! below:

The Woman Who Was Pregnant with the Messiah (at 64)

In 1844, Americans Sold All Of Their Stuff Because Jesus Was Coming Back

In 1910, Americans Thought Halley's Comet Was A Doomsday Event

In The '60s, The Truly Devoted Believed Aliens Would Save Us From Nukes