'Malignant' Was One (Literal) Second Away from Actually Being Scary

You know how mediocre and even bad movies end up getting love just because they have one actually good scene? Yup, if you've already seen James Wan's latest horror flick, Malignant, we're indeed talking about that scene. And if you've not seen it, beware: SPOILERS ARE COMING.

Wan's latest, frenetic submission to the horror genre is an undeniably fun ride, so if you're into trashy shlock, you better get on it. That being said, there is one scene -- revealing the entire film's gimmick -- where for all of his talent, Wan drops the ball. From its opening scene to its literal title, it is clear that the film's gory happenings have something to do with a tumor, a malignant tumor if you will.

Malignant is about Madison Lake, a woman who begins seeing visions of murders after her douchebag husband gets killed by a shadowy figure invading their home. The visions turn out to be actual killings, and so a police hunt begins. The villain is eventually revealed to be a parasitic teratoma, Gabriel, sharing a brain with Madison and acquiring full, mind-hacking, body-altering control over her during its murderous rampages. Evil Kuato from Total Recall, basically.

Don't Miss

Here's we arrive at the one little problem (with big consequences) with the way Malignant's twist is delivered.

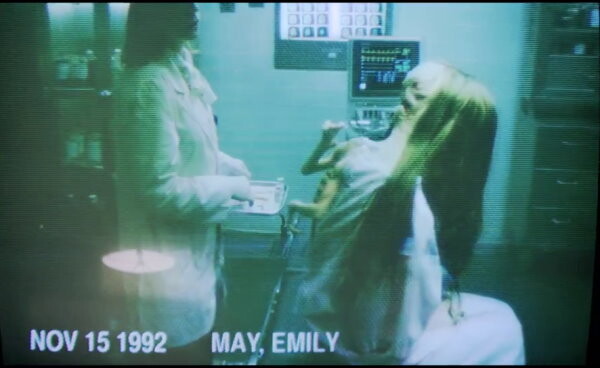

In the movie's third act, Madison's sister finds an old videotape. While watching it with their mom in a great little segment of found-footage dread, they see a child Madison sitting on a hospital bed and facing the camera while doctors talk to her. The camera then moves around to her back as the main doctor discusses the need to "Cut out the cancer." And then the movie's money shot: Gabriel actually moving and screeching with its turd-like face just in the back of Madison's head, with its little arms flailing about like a drunken T-Rex.

Really creepy stuff. Or so it could have been if Wan -- in a puzzling moment of restraint from a notoriously overindulgent director -- didn't rather choose to cut the shot short and immediately focus on Madison's relatives reacting to the videotape.

Using characters' reactions to help construct an emotion is not the problem here; this is just one of the wonders of film editing and a well-known Spielbergian trick. The problem with Malignant's specific cut from videotape to reaction is Wan not letting the shocking image of Gabriel sink in. As if he didn't trust the power of his own reveal, Wan just cuts it way too early in order to show how the movie's characters react, without having even given us the chance to react to it in the first place. The movie does show the evil little turd again after this reaction shot, yet the issue is that there is only one first time to show it, and once you've missed that key window, only diminishing returns are left, and the (now mainly vicarious) fear becomes a fraction of what it could have been.

And now I know you're thinking, "Talbert, you're obviously a sex machine, we get it, but this is just nit-picking." To this, I say, hey, first day on the Internet, uh? But also, remember that up to this moment, we viewers are pretty aware that Malignant's baddie is a tumor. But what we don't know is precisely what's revealed in this scene: that the killer tumor lives inside Madison's skull -- and not metaphorically, like your ex, but literally living there. To thus really hammer home the lost opportunity here, see this scene which proves my exact point:

It’s so sad Shyamalan quit the film business after Signs and never made another movie again. What a talent we lost.

This scene works for a million reasons, but notice what happens right after the alien walks through the shot. If you said Joaquin Phoenix jumps in horror (just like the characters in Malignant), you'd be wrong. What happens immediately after is that Shyamalan allows the camera to linger for just a second -- maybe even less -- on a parked car in the background. This introduces my future article, "7 Reasons Why Cars Were The Real Villains of Signs" (the seventh reason is the car crash that killed Mel Gibson's wife, of course), but it also serves another purpose.

You see, the human brain is a complex machine, and it constructs a total cinematic experience out of the slightest information available. Imagine watching that scene from That Movie with the Dumb Water Aliens for the first time (or remember when you first saw it). The familiar car allows the unfamiliar image of the alien to linger on, and so even before cutting back to the screaming children and Phoenix's reaction, terror has already begun stacking up, and chills begin running down spines. Basically, you have to give a minimum amount of time for the creepiness factor to build up, the scary image to settle in, and the brain to picture it "in the mind's eye," as Scott Pilgrim would say.

The movie provided the little empty moment for you to have its coolest scene imprinted. For another example, see the videotape scene from The Sixth Sense constructing dread with a similar rhythm. This is what Shyamalan allowed -- and what Wan didn't. This is why even going back to the creature after the reaction shot does not really work in Malignant as it did in Signs. Things like pumping up the jump scare music, showing a character reacting to the scary image, or even this image for a second time are just Shyamalan's ways of amping up a horror that is already there, of squeezing an original scare we're already riding. But he had to scare us in the first place.

What Wan then lost was a magnificent opportunity to raise his movie to the next level. From mere fun-yet-creepy shlock, it could have provided at least one moment of genuine, spine-tingling horror. Not the appearance or aesthetics of horror, but an actual, body-shaking shudder instead of having the viewer have her "What is that? Is that…? HOLY CRAP!" shiver interrupted halfway. It's a small, almost trivial change. But like a butterfly metaphor causing an almost decent Ashton Kutcher movie, its effect could have been magnitudes bigger.

Top Image: