4 Fan Theories That Explain Why Movies Make No Sense

A surprisingly large portion of fan theories come down to some variation of “it’s not real.” Bond died while being tortured, and we’re seeing his dying fantasy. Saved by the Bell is all about Zach’s dreams right before the alarm clock wakes him up. The Schumacher Batman movies are actually in-universe movies in Tim Burton’s Gotham.

These theories are all stupid, and they are all brilliant.

They’re stupid because when something in a movie is unlikely or silly or escapist, we don’t need an explanation for that. We already have one: It’s fiction. Fiction need not be realistic and need not even make literal sense. When the events in Beau Is Afraid or The Substance are absurd but seem to work as an allegory, it’s not because the character is experiencing something more mundane and hallucinating all this. It’s because the writer simply wrote the story that way.

Don't Miss

But these theories are also brilliant because each really does unearth a truth about the story. Sure, maybe Jack in Titanic isn’t “really” just Rose’s fantasy, and maybe Hogwarts isn’t “really” Harry Potter’s. But they are fantasies — both the writer’s fantasy and yours. And once you see them that way, everything snaps into place.

‘It Ends with Us’ Is the Fantasy of 15-Year-Old Lily

It Ends with Us is the biggest film of 2024 that’s not part of some existing movie franchise. It’s about Lily Blossom Bloom, who must choose between two guys, a vampire named Harry Styles (or “Ryle” for short) and a werewolf named Atlas (that’s his actual name). At least, that’s what the movie appears to be if you were dragged to it, previously knowing only the cheerful marketing campaign where Blake Lively invited you to come wearing florals. It turns out to be about someone escaping an abusive marriage, which contrasts quite a bit with the previous bubbly tone.

The abuse comes as no surprise, of course, to all the viewers who first read the bestselling book that the film adapted. Within the book, however, those dark parts clash even harder with the rest. They’re the only parts that feel real, while the remainder steers so hard into romance tropes, it feels like parody. For example, Lily has a Gay Best Friend, who appears just once, to firmly mark this as a romcom, before vanishing, never to be mentioned again. Characters constantly refer to Ryle as a neurosurgeon, which feels unnatural, both because there are situations where you’d more likely call someone like that simply a surgeon or a doctor and because it’s impossible for someone to be neurosurgeon at his young age.

Columbia Pictures

That’s one timeline in the book, in which Lily is 23. The other chunk of the book comes in the form of diary entries Lily wrote when she was 15, and the events in the future happen to match up very neatly with what she wants for herself when she’s a teen.

In the past, she has an abusive father, and in the future, he dies young, letting her clown on him at his funeral. In the past, she fantasizes about owning a flower shop. In the future, she opens one easily. It even becomes the most successful flower shop in Boston, for no clear reason, and she has only one employee, who appears one day and volunteers to work for free. In the past, she has a boyfriend who’s homeless, her father kicks him out and the boyfriend exits her life. In the future, she randomly bumps into him, and he’s made a great success of himself.

Columbia Pictures

In the future, she has a meet-cute with a guy (a successful guy, of course), bumps into him later by complete coincidence and soon marries him. Once they’re married, he ends up hitting her and worse, and we know that’s no one’s fantasy. But remember what I said about this being the only part that feels real? That’s because the rest of the future plot is the daydream of a girl imagining what adulthood and romance is like, while this detail ruining the fantasy is her knowledge of the real world creeping in, based on the one man she knows — her abusive father.

Afterward, the fantasy returns. She leaves her husband, which is something her mother never did, and the story very much frames this as Lily succeeding where her mother failed. She ends up with the other guy, again by bumping into him randomly, because the rules of romance are restored. And abusive husband Ryle actually supports her decision to divorce him, conceding that it’s the correct thing to do. A fair number of viewers say this was the single most unrealistic part of the whole thing.

‘The Many Saints of Newark’ Is a Movie Scripted by Comatose Christopher

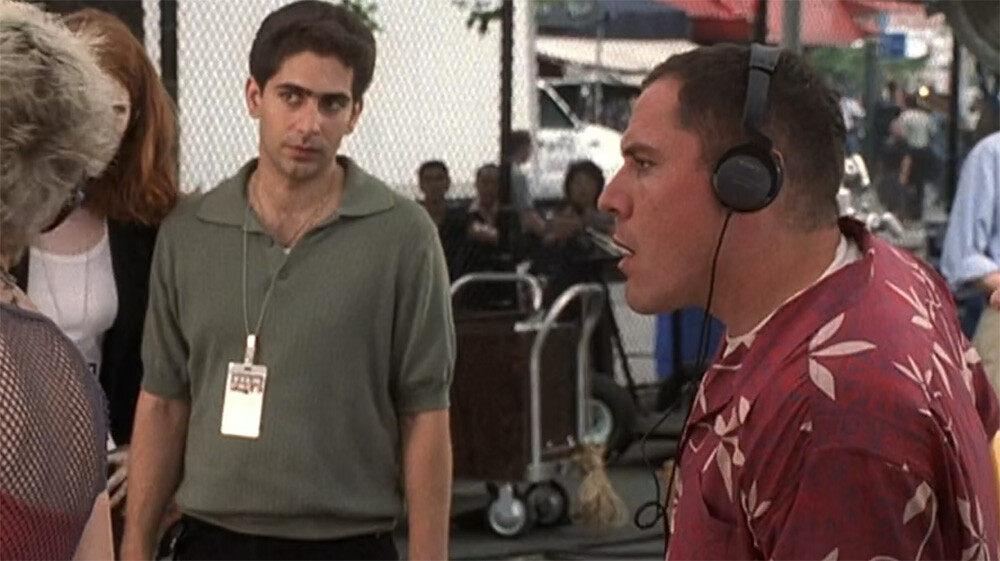

When a TV series becomes a movie, we hope for something better than just a couple of episodes strung together. This didn’t happen with the 2021 Sopranos prequel The Many Saints of Newark. Part of the movie covers new characters, and this is fine enough, but it isn’t on the level of one of the most acclaimed series of all-time. The other part of the movie covers younger versions of characters we’ve seen, and when you ask new actors to do impressions of known characters, it feels more like an elaborate skit than a straight movie. Here’s a clip:

Okay, that was actually an SNL sketch called “The Sopranos Diaries,” made eight years before Many Saints, but it’s the same basic thing.

The movie also makes the unusual decision to open with narration from Christopher Moltisanti, a character (spoilers ahead, but why are you even reading this if you’ve watched neither The Sopranos nor Many Saints of Newark) who is not born yet when the movie starts. He died during The Sopranos, and he is talking to us in the present about these things that happened in the past. Then in the movie’s absolute final scene, he reveals that he is speaking to us from hell.

Warner Bros.

No, seriously, the movie plays The Sopranos theme song here.

That’s pretty wild. There are actual Christians who choose not to believe in a literal hell, and here’s this movie officially declaring that in the Sopranos world, hell is real, and at least one character we know definitely ended up there.

But this isn’t the first time The Sopranos talked about Christopher being in hell. In one episode in the second season (written by Christopher’s actor, Michael Imperioli), he’s shot and enters a coma. Doctors say he clinically dies for one minute. When he wakes up, he says he visited hell. His thoughts there were of his father getting whacked, which just so happens to be the climax of The Many Saints of Newark. It’s sounding awfully like Christopher in the film isn’t narrating from after he died toward the end of the series but during that time when he thought he was dead in hell, in Season Two.

Now, some things he says in the movie don’t quite line up with this. He says Tony choked him, which happened at the end of the series, not the coma incident. Let’s say he’s talking metaphorically there. Anyway, some things he says also don’t line up with the real death we see in the show, either. Fans note that the road where he says he died was not the road where Tony killed him, so let’s say it’s the road where he was earlier shot.

That episode where he’s shot came two weeks after one devoted to Christopher trying to sell a mob movie to Hollywood. When he falls into a coma, we therefore know he had scripting a mob movie on his mind, and we also learn he had his father getting whacked on his mind. So, everything we see in The Many Saints of Newark isn’t necessarily something that happened in real life, as the movie shows events that narrator Christopher never witnessed. They’re events imagined by Christopher, in the form of a mob movie, the very thing he’d been trying to write.

HBO

This explains why the movie is about the Moltisantis (the “Many Saints”), though we can think of many plots we’d rather see. It’s why Christopher's dad feels more real than the other characters. It’s why the age gaps between characters are straight-up wrong, as Chrissy doesn’t know the exact ages of all these people one generation above him, so they all just seem to him like contemporaries.

It’s also why the movie isn’t very good. It’s because Christopher isn’t a good writer. That’s not me being judgmental — the show puts a lot of trouble into showing us that Christopher can’t write movies well. It cannot be coincidence that they chose for this mob movie to be narrated by someone known for being bad at writing mob movies.

‘American Fiction’ Is an In-Universe Script Designed as Awards Bait

In last year’s American Fiction, author Monk Ellison is annoyed that his work is pigeonholed as African-American lit. So, he writes a deliberately terrible book initially called My Pafology, a “ghetto novel” filled with every stereotype he can think of. It becomes a huge hit, with hack critics praising it for its authenticity. Meanwhile, we see glimpses of Monk’s own life, which are more complex than anything he wrote about. Finally, he’s invited to adapt the book into a movie, and he instead chooses to adapt the true story of how he wrote My Pafology. Meaning, he creates the movie we just watched.

Orion Pictures

It’s a great movie. But when the characters throw around the words “awards bait” and “Oscar-baity” with reference to Monk’s awful book, we can’t help but be aware that the actual movie we’re watching did win awards and did win an Oscar. The movie’s telling us critics are suckers for Monk’s fake story, but we know real-life critics praised Monk’s real story.

And some of those real story elements, like a death in the family, dealing with a parent’s dementia or a relative who comes out of the closet and loves doing drugs, are the very elements that we’d call awards bait now. The presence of Sterling K. Brown, who was nominated for an Oscar for this movie, reminds us of this because those exact elements also appeared in his TV series This Is Us.

Orion Pictures

To understand what’s going on here, you should know American Fiction is based on Erasure, a book written in 2001. At that time, some of the stuff we treat as groanworthy stereotypes today really were awards bait, and some of the stuff we consider awards bait today were considered far more unexpected, at least when given to Black characters. The book also has a little more time to spend on Monk’s life, so we see more real stuff that’s hardly awards bait, like Monk randomly going dancing one night and his dick popping out of his pants.

The conclusion, where My Pafology gets a film adaptation? That doesn’t happen in Erasure. It’s only in American Fiction. This may well be the most memorable part, because the characters debate several alternate endings, each ridiculous in its own way, and we see clips of how they’d play out. Monk agrees to one that didn’t actually happen to him. And though the movie doesn’t draw attention to it, the idea they settle on (police shooting an innocent Black man) is more relevant today than much of the stuff in My Pafology, which was written in Erasure for a 2001 audience.

So, if Monk was willing to insert that bit to win awards, willing to insert something that resonates with 2023 critics, how many other parts that we watched and took at face value might he have invented for the same reason? The final shot shows that his brother was real, but we don’t know how much of the rest was. Maybe his mother never got Alzheimer’s, maybe their housekeeper never got that heartwarming wedding — we don’t know.

Though, if Monk did invent stuff to cater to critics, that doesn’t mean we can’t appreciate watching it. In Erasure, they include 70 uninterrupted pages of My Pafology, and by the end of it, you might forget you’re reading satire and enjoy that, too.

UPNE

‘The Last of Us Part II’ Doesn’t Show Us What Really Happened at All

The Last of Us (no connection to This is Us or It Ends with Us) is a video game series set after a zombie apocalypse. HBO has adapted the first game for TV, and they’re now doing the second one, in which Ellie embarks on a quest for revenge. Partway through the game, we switch points-of-view and play as Ellie’s target, Abby. We discover the two are quite similar, right down to the motives behind their revenge quests, and it all comes to a head when they meet and try to kill each other.

Neither does kill the other, and we get an epilogue, followed by Ellie hunting Abby down again, which ends in their again fighting and again not killing each other.

Naughty Dog

Some vocal players disliked this game. Some said Ellie should have killed Abby, giving the player catharsis. We can safely say such players missed the point, or that the game failed to make its point, because you were supposed to end the game not wanting either to die. You play as them both. They are both you.

However, just because you learned where both characters are coming from doesn’t mean either of them did. Whatever lessons each learns about loving particular people over the course of the game, each retains their vengeful desire to kill. We know this because we see them continue to kill. In the scene before their showdown, Abby discovers Ellie killed even more of Abby’s friends, and in the seconds before the showdown, Abby kills more of Ellie’s. These are all important named characters whom we came to know over the course of the game.

Naughty Dog

They also kill scores more unnamed characters, during gameplay, and I’ll brush past those because games and movies expect you to ignore those when considering the story. I probably shouldn’t with this game, though. Its entire premise is: “What if an unnamed character you killed during gameplay in the first game was as much of a person as you, complete with a daughter who’ll mourn him?”

Either way, given both characters’ motives, the most honest way to end the game would be for them to go through with it and kill each other. In that showdown, each holds a hostage (the third- and fourth-most important characters in the game), and each should kill that hostage. Then they should kill each other. Roll credits. The story would fulfill its promise as a tragedy, and the player would be completely devastated. They would leave the game taking to heart the message that was lost on the characters (and was evidently lost on so many players, in the game we actually got) — murderous vengeance is pointless and bad.

Naughty Dog

So, perhaps Ellie and Abby should have killed each other. And perhaps they did kill each other.

Because after that showdown, we cut to a new scene, and it’s not the immediate aftermath, showing the surviving characters mourning the horror that just hit them. It’s after a time skip, and we now see Ellie and her girlfriend running their own farm while also raising a baby.

It’s a positively idyllic scene, happier than anything we’ve seen in the game before. Then it fades away as Ellie sees frightening images, and we say to ourselves, Oh, of course. This farm scene isn’t real. Now we’re about to see what’s really happening. But no — the frightening images are PTSD flashes, while the perfect farm is real.

Casually tending to a farm with a baby on your hip is a common fantasy. It was a common fantasy in 2020 when the game came out, and today, we have a name for it: It’s the tradlife fantasy. And since it’s such a widely discussed fantasy today, various people (including many actual farmers) pipe up to explain it’s delusional. Running an independent farm is intense work, far more laborious than many other jobs. It’s intense for anyone, and it would be especially intense for these two waifs without farming experience who also must take care of a newborn.

That would be true in our world, where we have industrialization and commerce, a world where you can order fertilizer and seed in bulk online. After society collapses, it would be much harder. And society didn’t merely collapse in The Last of Us. It collapsed from a zombie apocalypse. Zombies and gangs of bandits roam everywhere, even more so in the game than in the TV adaptation. Towns erect high walls for protection and still need dedicated armed patrols to fend off each day’s threats. Maybe a farm surrounded by wilderness with just a wire fence on all sides is a smart move in your zombie apocalypse, but in this one, it means death.

Naughty Dog

The two of them cannot be peaceful and relaxed here. This cannot be real.

So, perhaps it is just Ellie’s imagination after all. Because she and Abby did fight, and now, she’s bleeding out and seconds from death. This farm scene is her wondering to herself: If Abby just walked out of here, could I have let go of this obsession? Could I have just gone off somewhere with Dina and been happy? Maybe not. Maybe Tommy would have shown up one day with news on Abby’s whereabouts, and I would have hunted her down and killed her in the end.

Or maybe I would track her down, but maybe — based not on anything that happened to me before but based on how I am now dying and now finally know just how doomed the cycle of revenge really is — in this imagined scenario, I would spare her after all. Maybe it ends with us.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.