4 Monopolies Behind Where All Sports Stuff Is Made

Sports may span the nation or the globe, but the materials that players use tend to be standardized. Sometimes, this results in an outright monopoly by one manufacturer, and even when there’s no literal monopoly, it can be bizarre to take a step back and see everyone using the same stuff.

Did you know that most dirt in baseball parks nationwide comes from one location in Pennsylvania? And that half of all soccer balls worldwide come from one town in Pakistan? For more oddly centralized sports materials, consider how...

All Baseballs Are Coated in Mud From One New Jersey Vendor

Roughly six seconds ago, we mentioned how most MLB baseball diamonds get their dirt from a borough in Pennsylvania, which goes by the name of Slippery Rock. Crazily enough, there’s another location in the Mid-Atlantic that provides dirt for all baseball parks nationwide — only, this dirt doesn’t go on the ground. This dirt serves a higher purpose.

Don't Miss

See, when a baseball is brand-new, it’s a little too smooth and shiny. You can’t throw or catch it as comfortably as you could a ball with a little more texture.

The solution, you might imagine, is to change the manufacturing process to make balls with a little more texture. The actual solution we use is having some equipment manager manually rub mud on new balls to wear them in a little. That solution, you might now imagine, is a hastily thrown-together quick fix, using the closest material available. But the mud comes from one riverbank in New Jersey, and every baseball park imports this same mud because no other mud will do.

One company has provided this mud for the past 70 years. It’s called Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud, and we know they skim mud from the banks of some southern New Jersey tributary of the Delaware River. But where specifically is this bank? That’s a secret that the company refuses to disclose and that no one has been able to discover. If you found out, Lena Blackburne Co. fears that you’ll head on over and rub your balls in the stuff yourself.

Curling Stone Comes From One Tiny Scottish Isle

You may go years of your life never thinking about curling. Then come the Winter Olympics, and we’re all reminded of that ridiculous sport where people, on ice, slide a granite stone — a slippery rock, if you will. This is no gimmick sport but instead perhaps the oldest team sport in history. The players come from Italy, from Canada, from Norway, from Japan and from various other countries. The stones, every one of them, come from here:

That’s Ailsa Craig. It’s an uninhabited Scottish island, just a couple hundred acres big, and it’s got itself some granite quarries. A lot of other places also have granite quarries, of course, but everyone’s convinced Craig’s island has special granite, granite harder and more consistent than granite we’ve found anywhere else.

For the past 600 years, the island has been owned by the Kennedy family. Not the American political dynasty the Kennedys but a real dynasty, headed by centuries of earls and marquesses (five of whom, incidentally, were named John Kennedy). In 2013, the man in charge was Archibald Angus Charles Kennedy, a one-legged tour guide who realized his peerage wasn’t bringing him any money. He put Ailsa Craig for sale for $4 million.

No one bought it. He lowered the price to $2.4 million. Still, no one bought it. Then a wildlife trust supposedly bought it, but we’ve seen reports of it still for sale since then, so we encourage you to put in an offer, after which one Olympic sport will become legally yours.

All Basketball Floors Are Maple Wood, Because Science

The very first basketball court was made of maple wood, for a simple reason: It was the closest thing available. For that same reason, they threw balls into peach baskets instead of stitching nets to hoops like we do today. But by crazy coincidence, maple wood happened to also be the best floor material in the world.

Wood afficionados score different kinds of wood using something called the Janka hardness rating. Maple’s rating makes it resistant to damage but also able to spring back against force, which makes it easy on athletes’ joints. We’ve spent more than a century playing trial and error with various other types of wood (and also stranger materials, like canvas), and we’ve never found anything better than maple. And so, every basketball court uses maple.

Unless you’re Boston. The Celtics debuted their floor right after World War II, when normal lumber was being grabbed by new homes for returning servicemen, so the Celtics had make do with scraps of oak. That design became so iconic that they stuck with it, even as they replaced the old wood when they switched arenas.

AstroTurf Is Named for the Astrodome and a Wacky Disaster

Right now, the world is talking about Aaron Rodgers tearing his Achilles tendon. This has led people to debate the relative safety of artificial turf — or “turf,” as it’s simply called — versus natural grass. Turf versus grass sounds like a strange way of summarizing the choices, since “turf” literally means grass. But that name is convenient due to people using it as a short-form for “AstroTurf.” People don’t use the full word AstroTurf because that’s a brand name, referring to the one specific company’s product.

Today, in fact, while several NFL stadiums use artificial grass, not one of them uses AstroTurf. However, every single United Soccer League field has now been contracted to switch to AstroTurf. That could be inconvenient when the U.S. hosts World Cup matches in 2026, since World Cup games have to use real grass.

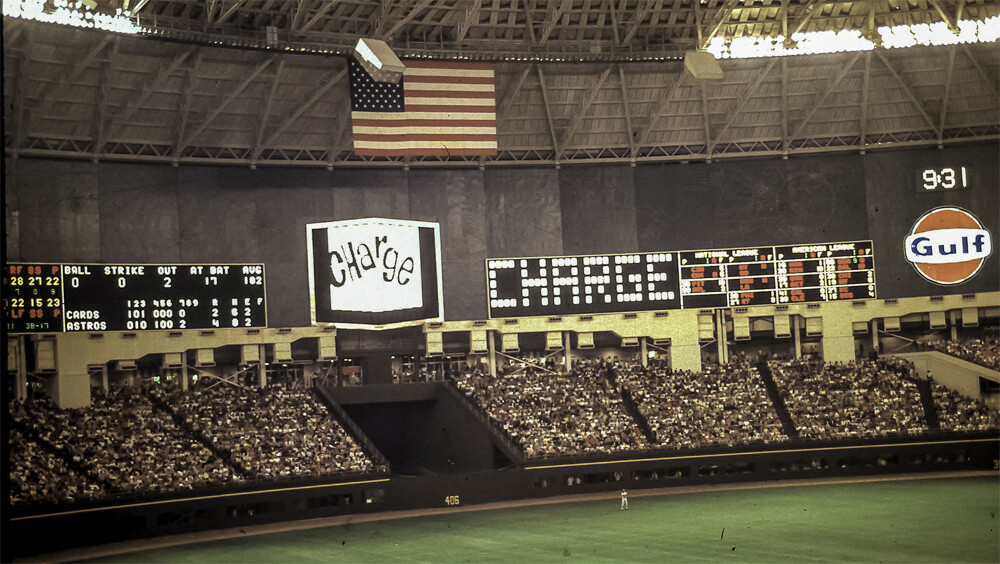

We wound up with AstroTurf because of something that happened at Houston’s Astrodome 60 years ago. The stadium was built with a roof (an unprecedented move in baseball) to allow for air conditioning. They had to engineer a special kind of grass that could grow indoors, under reduced sunlight. But the clear panels of the dome, which allowed some light through, looked weird to players and messed with their ability to track balls. So, they went and painted the panels white, and even Frankengrass can’t grow with no sunlight at all. In 1965, all the grass died.

In their desperation, Houston now turned to scientists at Monsanto. The scientists had created the world’s first artificial turf, which they called ChemGrass. Not enough ChemGrass existed to cover a whole baseball diamond, but Houston bought as much as was available. From then on, the product was dubbed AstroTurf. It’s still called that now, even though the Astrodome is no longer in operation.

The name origin hits weirder if we extend the timeline a little. Today, we don’t primarily associate the word “astroturf” with sports at all. We talk of astroturfing, which is the process of a political actor creating a movement that presents itself as natural (“grassroots”) but isn’t.

Let’s also extend the timeline in the other direction. AstroTurf is named for the Astrodome. But why was the Astrodome called that? It was named for the Houston Astros, of course — who now play in Minute Maid Park, on real grass. And why were the Astros named that? They were named (following a brief stint as the Colt .45s) for the concept of astronauts, since Houston was home to Mission Control, the place we now call the Johnson Space Center.

And why is Houston home to the Johnson Space Center? You might hear a lot of reasons Houston is a good spot for such a facility, but the ultimate reason is that NASA’s budget was decided by the House Appropriations subcommittee, and their chair was Albert Thomas, the Congressman from the Houston area. So, when you hear “astroturfing,” you think “shady political maneuvering.” When you really dig into the history of the term, however, it actually means... shady political maneuvering.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.