Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time: 4 Ways Filibusters Turned Awful

Are you prepared to lose any faith you may have had left in democracy? Well then, we’re gonna discuss a procedural rule in our government that A) technically isn’t supposed to be there in the first place, B) was never intended to be used the way that it has, and C) is generally only supported by the most punchable faces in Washington, D.C..

Oh, those criteria don’t exactly narrow it down, does it? It’s the filibuster. Whelp, let’s get into it …

A Brief, Disheartening Summary of the Legislative Process

Don't Miss

Surely by now, we’ve all seen the Schoolhouse Rock I’m Just a Bill cartoon explaining how a bill becomes a law. If not, here you go:

This song is quite possibly the perfect encapsulation of the American legislative process: It’s only three minutes long, and it spends all but about ten seconds of that time talking about how everything could fall apart at any moment. Not to mention the fact that the anthropomorphic bill singing the song repeatedly has to rely on hope and prayer to keep himself from crumbling into complete despair. However, the bill’s fears are completely justified because, statistically speaking, its odds of survival are not great, and even if it makes it through this gauntlet, it may not be the same as when it first started.

Before a bill can even be introduced, it has to be studied and debated by a committee specific to that legal arena. If the topic of the bill falls under the jurisdiction of more than one committee, it will go to a joint committee. If there isn’t a committee that covers it, they’ll form a special committee. Most of those committees consist of smaller sub-committees. The eye twitches you’re experiencing right now are totally normal.

If the bill even makes it out of committee, guess what? Then it goes to the Rules Committee to decide if, when, and how the bill will be debated, amended, and voted on. Two steps into this process, and already it’s a miracle the bill from the cartoon didn’t off itself with a letter opener.

Then, the House of Representatives will debate the bill, amend it, debate the amendments, debate the whole damn thing again, and ultimately vote on it. If it passes, it is sent over to the Senate, where they do the same thing under a different set of rules. If the Senate makes any changes to the bill, it gets kicked back to the House, and the whole process repeats itself until both houses of Congress pass the same version of the bill. Did we mention all of this is being done by a bunch of career politicians with a current 20% approval rating?

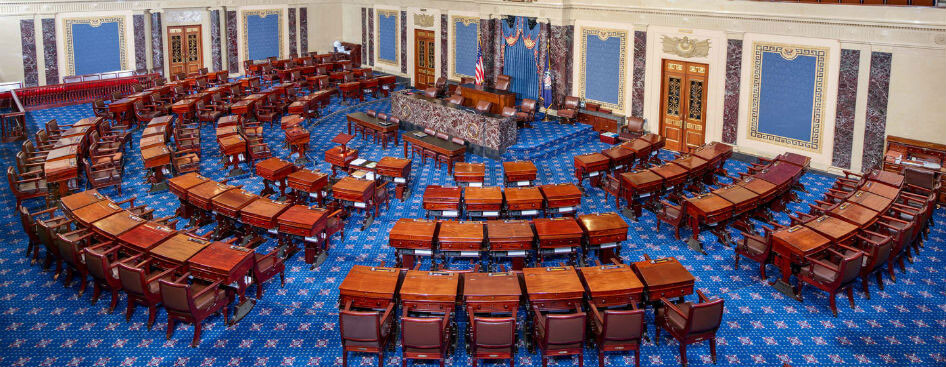

Michael J Thompson/Shutterstock

Once the bill passes Congress, it gets sent directly to the President’s desk, where The President has ten days to decide to either sign the bill into law, veto it, or … do absolutely nothing. After 10 days, the bill must officially be returned to Congress, with or without a signature. If Congress is still in session by then, the bill becomes law by default. If Congress has adjourned … Well, there’s no one there to officially receive it, is there? So, the bill dies unceremoniously in what’s called a pocket veto.

Surely the pocket veto is another one of those weird, legal technicalities we’ve just never bothered to fix, right? No President wouldn’t use this just to give Congress the finger, would they?!? Only 32 out of 46 of them … a total of 1066 times.

The Filibuster and Why It’s Such a Problem

One of the biggest logjams in getting a bill passed is the ever-present threat of the filibuster rule, a Senate tactic that always manages to sound worse the longer it takes to describe it.

In order for a bill to pass the Senate, it requires a simple majority vote of at least 51%. If the vote is split at 50-50, the Vice-President would cast the tie-breaking vote. But in order to get to vote on the bill, they must first end the debate over the bill. The first step is for someone to ask for unanimous consent. Basically, asking the entire Senate, “Hey, does anyone have a problem if we go ahead and vote on this thing?” If no one objects, they proceed to vote on the bill. Easy peasy, no one’s acting sleazy.

If there is an objection, they have to file a cloture motion, which requires a supermajority of 60% in order to pass and move on to the vote. This is where the filibuster comes into play. A group of Senators in the minority could conspire to prevent the passage of a bill by making sure they have enough votes to prevent cloture from happening and keep the debate going on indefinitely, purely out of sheer partisan spite.

Thankfully, this almost never happens out of nowhere. More often than not, Senators will announce their intention to filibuster a bill before it even reaches the Senate floor, so the opposing side can at least plan out a strategy to prevent that from happening. This ostensibly means that if a bill seeks to address a problem that has been turned into a highly polarized wedge issue, it has to achieve 60% support in order to guarantee it passes instead of 51%. Because if the opposition can get 41 senators to agree to never let it come to a vote, then the bill is as good as dead.

But wait, isn’t everything in American politics turned into a polarized wedge issue these days? Yup, that’s the problem. That’s why so many bills that pass the Senate seem to be so watered down from the original idea; they have to make these concessions to prevent one side from threatening to invoke a filibuster. Think of it this way: Imagine trying to get seven people to agree on toppings for one pizza, but because three of them are told they can’t have anchovies, those three threaten to burn Pizza Hut to the goddamn ground. So by the end, everyone’s eating Taco Bell because they wasted so much time that it was the only thing everyone could agree on.

Shisu_ka/Shutterstock

It’s important to note that the House of Representatives does not have a filibuster rule. Everything that makes it to the House floor is pretty rigidly timed because they have 435 members to contend with. Each side of the debate has X amount of time to speak, and each speaker has a set time limit, where they can reclaim their time if interrupted and yield the remainder of their time if they wrap up early. It’s still a hyper-partisan dumpster fire most of the time, but at least someone’s keeping an eye on the clock.

The Senate is intended to be a slower, more deliberative body than the House. Bills could be rushed through the House so fast that its members may not have enough time to read the damn bill before voting on it. The Senate can take all the time it needs to parse, amend, and debate a bill. People often complain that the Senate never gets any work done, when in actuality, they’re working their asses off… trying to sabotage one another. They spend so much time trying to make a political statement that they often forget to make any actual progress.

The Rules Got Weird Over The Years

The Filibuster sorta happened by accident. Until 1806, there was a procedural rule that allowed Senators to motion for the previous question, which meant anyone could shut down the entire debate at any time by calling for an immediate vote. At the suggestion of then Vice-President Aaron Burr (yeah, the guy who shot Hamilton), the Senate decided to eliminate the previous question rule to allow debates to reach their natural conclusions.

However, they didn’t put in any standard rule in its place to call for the end of the debate, and this is where the filibuster became a theoretical loophole that could be used in a very dickish way. The bill can’t pass if they never stop debating it, so all they had to do is keep talking until enough people switched their votes just to get them to shut the hell up!

The concept of a talking filibuster would be hilariously absurd if it wasn’t such a pain in democracy’s ass. The rule was that if a Senator wanted to filibuster, it was literally a put up or shut up situation. If they wanted to single-handedly hold up a vote, they would have to remain on the Senate floor and talk non-stop. They didn’t even have to keep talking about the bill, they just had to keep talking. They were allowed to eat and drink, but they were not allowed to sit or leave the floor to go to the bathroom.

In 1957, Sen. Strom Thurmond set the record by spending 24 hours and 18 minutes on the floor trying to prevent the passage of the Civil Rights Act. This guy really didn’t want black people to vote. Horrific racism aside, you gotta admit this was an unbelievable feat of endurance for a 54-year-old heavy smoker. He didn’t just pull this off due to the darkness of his soul. though. He came prepared.

White House Press Office

He had throat lozenges in his pocket and snacks at the ready. He took steam baths for days beforehand to dehydrate his body in order to be able to drink fluids during his speech without needing to go to the restroom. He did take one pee break about three hours in though, temporarily yielding the floor to allow Barry Goldwater to insert something into the Congressional record. Thurmond’s aides kept a bucket ready for him in the cloakroom in case he needed to relieve himself again while keeping one foot on the Senate floor.

In 1917, the Senate instituted a rule where a two-thirds vote would be enough to end a debate and shut down a filibuster. It didn’t make the filibuster go away, it only made it a team sport. Instead of one Senator delaying the process, a coalition of one-third of all of them could hold it hostage. In 1975, they changed that threshold from two-thirds to 60%, which is where we remain today.

The filibuster was also a serious problem because, until 1970, the Senate was only allowed to debate one bill at a time, so a filibuster would grind all the Senate’s work to a screeching halt. Now they have a two-track system where they can decide to table that debate for now and move on to other business in the meantime. Once that business is handled, they can pop back in to see if everyone was back on their bs.

Getting Rid of the Filibuster

Talk about eliminating the filibuster is at a fever pitch these days, and it’s not hard to understand why. Neither party has had a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate since the seventies, and the battle of right vs. left has only gotten more intense since then. Eliminating the filibuster could take away much of the deadlock in the Senate, but neither party really wants to pull the trigger. Many members in the minority don’t want to get rid of the biggest obstructionist tool left in their arsenal, while some members in the majority don’t want to get rid of it because they know they might be one election cycle away from being in the minority.

The process for getting rid of the filibuster is really quite simple: The Senate just has to vote on it. The biggest irony over that is just like any other decision the Senate makes, it has to be debated, which means the act of ending the filibuster could itself be stalemated by a goddamn filibuster!

There is a reverse Uno card to the filibuster though, and it’s called “the nuclear option.” It breaks down like this: The Senate Majority Leader raises a point of order that contravenes a standing procedural rule… something like, “Hey, this 60 vote cloture thing is stupid. A 51 vote simple majority ought to work just fine, right?”

The presiding officer then denies the point of order: “That’s a no from me, dawg.”

The Majority Leader appeals the ruling and calls for a vote: “You sure about that? Show of hands, everyone?”

Only a simple majority is needed to overrule the ruling, in which case the presiding officer must adhere to that decision: “Well, crap.”

U.S. Senate

This power play has only happened twice. In 2013, then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid invoked the nuclear option to eliminate the filibuster for any Presidential or judicial nominees other than those for the Supreme Court. The reasoning behind this was these positions needed to be filled quickly, there was far too much work that needed to be done, and there simply wasn’t any time for partisan squabbling. The plan worked, but that doesn’t mean that every nominee just sailed through confirmation, though. Some of them got turned down, but at least none of them got held hostage by a garbage procedural rule.

The second time was in 2017, when the next Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, used the nuclear option to take Reid’s idea a step further and eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees as well. McConnell’s efforts weren't exactly as noble, though. The GOP wanted to install Donald Trump-appointed nominee Neil Gorsuch on the Supreme Court with as little obstruction as possible. Which would’ve been fine if they hadn’t been stonewalling Barack Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland for the previous 10 months.

Dick move, Mitch. Dick move.

Dan Fritschie is a writer, comedian, and frequent over-thinker. He can be found on Twitter, and he thanks you for your time.

Top image: Keith Lamond/Shutterstock