There Are Still 60,000 Slaves In America (And I Was One)

Get intimate with our new podcast Cracked Gets Personal. Subscribe for funny, fascinating episodes like "Inside The Secret Epidemic Of Cops Shooting Dogs" and "Murdered Sex Dolls And Porn Suitcases: What Garbagemen See," available wherever you get your podcasts.

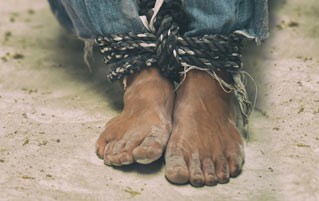

The United States has been officially slavery-free since 1865. But it wasn't a smooth road to get to that point, and a startling number of pick-up truck gates still express support for the practice. Maybe that's why some 60,000 people are still enslaved in the United States today. Cracked sat down with one of these people, Flor Molina, and talked about her experience being forced to work against her will. She told us ...

You Might Be Wearing Clothes Made By Slave Labor

If you bought clothing from a U.S. department store in 2002, you might've bought something Flor made while she was an unpaid, unwilling laborer. "Yeah, the dresses were sold in the department store here in the United States. I remember some names of the stores ... Yeah, I do remember three department stores in the United States. One is Macy's, one is J.C. Penney, and the other one is Sears."

Patagonia is the global poster child for environmentally sustainable clothes and 35-year-old liberals who want to look "adventurous." The company also goes out of its way to ensure the people who sew its clothing make a fair wage and work willingly. But even so, it found evidence of human trafficking in its supply chain as recently as 2011.

Even if the people making the clothing are treated fairly, that doesn't mean the people making the cloth itself are. Patagonia only caught the problem because they rigorously check for this kind of thing, but other clothing retailers aren't always so motivated. In December 2016, an organization called "Know the Chain" published a report on how well various fashion brands take action to eliminate human trafficking from their supply chain. Prada scored a 9 out of 100. Ralph Lauren scored a 45. Even Adidas only scored an 81, which is great compared to Prada but also still means there's slave labor in the production of your running shoes.

Flor Entered The Country Legally In Search Of A Better Life, And Still Fell Victim To Human Traffickers

Flor had the same dream as pretty much everyone: to make a little bit of extra cash for her family. Maybe someday, god willing, even buy an Xbox. Luckily for her, a friend just happened to know how she might do that. "I was contacted by my sewing teacher, because back then I was taking sewing classes. A trafficker contacted my sewing teacher because she knew a lot of women. My sewing teacher told me about the great opportunity to go to the United States."

Flor lived in Mexico, and she wanted a shot at making it in the land of opportunity, even if that meant sewing Polo shirts for the jerkwads trying to keep her out. She was told that her new employer would cover her travel expenses and provide her with a place to stay. It's one of those too good to be true offers which uh ... was. "So I took the opportunity to come to the United States, and that's where this nightmare started."

We should note that Flor didn't enter the U.S. illegally, if that matters to you. She had a passport, and she rode into this country in the passenger seat of a car. "I was a regular passenger, I was sitting next to the driver. I wasn't hidden or anything, I was next to the driver." That's fairly normal for her situation. Most trafficking victims enter the country through legal work visas. Only 29 percent of human trafficking victims are smuggled illegally into the United States.

Then They Stole Flor's Passport And Told Her She Owed Them Money

"I realized it was the wrong decision when I arrived in Tijuana and my trafficker asked me for my documents. I felt that something was wrong, I couldn't say exactly what it was. She said that for my safety, she'd keep my documents." Again, it's incredibly common for trafficking victims to have their passports seized by their captors.

Once her captors had her documents, Flor was stuck between a rock and the language barrier. Los Angeles may be close to Mexico, but to Flor, it was still a strange country. She didn't speak English or understand our customs about, like, Pogs and shit. At this point, she still thought the job might be legit. "When I arrived to Los Angeles, my trafficker told me that now I owe her almost $3,000 for bringing me over, and now I have to work for her, because now I have a huge debt with her and I must work in order to pay my debt. And I thought of course she used her money for bringing me over, so of course I have to work to pay my debt."

For a little while, things seemed normal. She worked in a factory with 50 big sewing machines during "regular business hours, workers who came and worked during business hours ... The first three days, I went back and forth to house and came into work to the factory, but after three days, she decided that I'm supposed to sleep in the shop. Because the time I was using going and coming back, I was wasting debt time, and that was her time ..." This is the point at which things flipped from "crappy job" to "Oh shit, did I just become a slave?"

Psychological Abuse And Fear Of The Authorities Kept Flor Compliant

Say you're an asshole who's decided to trick foreigners into entering the country on a work visa, steal their papers, and force them to work for you. How do you ensure that your new forcibly indentured servant doesn't flee? You can't watch them constantly; you've got mint juleps to drink and white linen suits to wear. Fortunately, you've got one thing on your side: the cops. " also told me that I'm not allowed to talk to anybody, I'm not allowed to go outside, I'm supposed to stay inside because if I go outside I put her in danger, and also the police will put me in jail because I am here illegally. I have no documents, no identity, no one will care about me. If the police put me in jail, I will never see my children again."

Of course, the police fight human trafficking, but U.S. law enforcement isn't exactly famous for its kind treatment of undocumented immigrants. So Flor found her captor's claims believable. For weeks, that was all they needed to keep her in line. But then the abuse started. "They often were physically abusing me -- pulling my hair, pinching me, slapping me, all the time telling me mean words, making me feel bad about my origin. All the time, they were telling me about the police, about the authorities. All the time telling that if I go outside and if I talk to anybody, nobody will believe."

It should be noted that the data suggests physical abuse is not common among human trafficking victims. Bruises raise questions. Psychological abuse IS incredibly common, though. "She also said that if I do anything to put her in danger, she knew where my family was, she knew where my children were, and I didn't want to put them in danger."

All Of This Happened In Plain Sight, But No One Knew

The factory where Flor lived and worked seemed like a normal one, mostly filled with normal garment workers. Most of what happened to her occurred in full view of people who'd have been horrified if they knew what was going on. Again, this is the norm. Some of you reading this have probably interacted with a human trafficking victim at some point and not known it.

"The factory didn't have a place to sleep. I had to sleep in a little sewing room, and I shared the mattress with my sewing teacher, who was also innocent and also in slavery. The factory also did not have a shower, we had no place to take a shower. I cleaned myself, you know I find a way to clean myself because there was no place for us to take a shower. As I said, I wasn't allowed to put one step out of the shop." She was told not to talk to her co-workers, and she wasn't allowed to contact her family. "So my family thought I had forgotten about my mother and my children."

Flor worked seven days a week, 18-20 hours a day. That made us feel a little bad for conducting this interview in our underwear while eating peanut butter directly from the jar. Her job involved "sewing, ironing, pulling the dresses into the right size, putting labels on the dresses, moving them to the proper racks, and putting bags over the dresses that were ready to go out, that they were ready for the store. And when the trucks came, I had to unload the trucks with the fabric they got to make the dresses. When the trucks were empty, I had to load them with the dresses that were ready to go to the store."

Since she was always present, some of Flor's co-workers reached out to her. They didn't know she was enslaved, and treated her like a normal employee. She even made a friend this way, a lady who gave Flor her phone number "in case I ever needed anything." Flor needed a whoooole bunch of things, actually.

Nobody Busted In To Save Flor -- She Had To Free Herself

Most human trafficking victims who get free do so themselves. Flor had to find a way to escape on her own. Now, before she'd left for America, Flor had made her trafficker promise to let her visit a church once she arrived. This promise quickly became Flor's lifeline. If she could get out to go to church, for even a few minutes, she might be able to escape. "She said that they have to earn the permission to go to a church. She gave me a lot of work, and when I proved that I really, really wanted to go to a church, she said, 'Why do you want to go to a church? You are a bad person.' And I said, 'That's why, I want to go and ask God to change my path.'"

Eventually, Flor's captors allowed her to walk out to a nearby church one Sunday. And "when I walked through the parking lot, I realized that I was free because that Sunday, to my surprise, no one was monitoring my movements. Nobody was there." Apparently, even modern-day slave drivers like to take Sundays off. They'd probably assumed Flor was too beaten down to flee, but they had her number wrong. Unfortunately, Flor immediately encountered some number-based trouble of her own.

"I tried to make the phone call. But the operator answered in English, and as I said, I didn't know what words in English. I didn't even know U.S. money -- you know, calling with dimes or anything like that. And I didn't have any money with me, so I tried to make the phone call. It was Sunday, and not a lot of people were on the street. But to my surprise, I saw a walking person and asked him for help. I asked him to dial the number, he dialed the number, my co-worker answered and came and picked me up from the corner of that place." And with that, she was free.

Justice At Last! Well, Sort Of ...

The next day, Flor's trafficker threatened her friend. Flor fled to San Diego, where she hid out until she received a knock at the door. At first, she thought it was her trafficker, come to take her back. It turned out to be the FBI. It seems members of a human trafficking task force had been watching the factory for a while. They busted the whole operation shortly after she escaped.

"So they brought me to Los Angeles and asked me to cooperate with them, because all my co-workers were in the detention center and my trafficker was free. My trafficker was blaming my co-worker who had helped me. My trafficker said she didn't know me, and I had never worked at her place, and the person that brought me over was my friend, the one that helped me."

Flor was terrified of the police, but she decided to cooperate, because seriously, fuck human traffickers. Her testimony helped put her captors away ... sort of. This was in 2002, a time before human trafficking was well-known to U.S. law enforcement. "So that's why my trafficker got a light sentence -- only six months of house arrest, a fine of $75,000, and that's it. She was judged as an 'abusive employer' rather than a trafficker, because back then, human trafficking was kind of a new topic for law enforcement, so they didn't know how to judge my trafficker."

Although honestly, that kind of thing still happens. In 2014, a Harvard couple was convicted of abusing and holding a Bolivian nanny against her will. They were fined $150,000. Once Flor's trafficker finished her time on house arrest, she immediately went to Mexico to harass Flor's family. "The last time I heard that she had contacted my family was in 2008, when she went to visit my mother, and give $20 to my mother, for my mother to call here as soon as she found out where I was. Later on, she went to my brother's house and forced my brother, intimidated my brother, to give her my address in the United States."

Being harassed after escape is also normal for people in Flor's situation. Luckily, she had some connections by this point. She called her lawyer, who contacted the U.S. Attorney's office, who found Flor's former captor and told her to knock it off. Flor became an activist. She is now a U.S. citizen, and she currently works her butt off to stop anyone else from suffering the way she did. Her testimony was a critical part of passing a California state bill which forces companies to disclose exactly what they're doing to keep slavery out of their supply chains.

Please note that the bill doesn't actually keep slavery out of any company's supply chain. It just means they've got to tell us how they're trying to stop it. There's still a long, long way to go to make sure the next pair of hot pants that Amazon Prime delivers to your door aren't made by modern-day slaves. If you really want to avoid supporting slavery, your best bet is still to buy your hot pants secondhand, or better yet, abstain from pants altogether.

If you loved this article and want more like it, please support our site with a visit to our Contribution Page.

Have a story to share with Cracked? Email us here.

Also check out 5 Things I Learned as a Sex Slave in Modern America and 5 Ugly Things You Learn As A Sex Slave In The Modern World.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and check out How One Escaped Slave Changed The American Civil War Forever, and watch other videos you won't see on the site!

Follow our new Pictofacts Facebook page, and we'll follow you everywhere.