5 Pieces Of Bonkers History Hiding In Classic Artwork

Great art comes in a variety of flavors. Whether it's a bowl of overripe fruit or a mythological Greek gang-bang … Okay, two flavors. For a foundational civilization, the Greeks sure skewed heavily toward gang-banging. Anyhow, between these two overarching themes, nothing soothes humanity's congenital need for creative expression and Classical T&A like a good piece of art.

Each of the fantastic specimens curated herein provides candid societal glimpses to boot, sure to supply that oh-so-nice feeling in the pancreas that makes one contentedly exclaim, "Mamma mia, that sure is a good art!"

The Tuscan Dick-Tree Reveals Medieval Witchcraft And Middle Ages-Propaganda

Don't Miss

L'Albero della Fecondita means The Tree of Fecundity and upon a glance, it’s looks like a painting of the countless fruiting trees dotting Tuscany's verdant, rolling hills.

But, at a closer look, there's one somewhat notable exception. Instead of bearing apples or oranges, it bears penises from its branches.

It resides at the marvelously mellifluous Fonti dell'Abbondanza, which sounds like some kind of church but isn't. Instead, it's something useful, a public fountain (fonti) of abundance (abbondanza) and granary that served as the main water supply for the Tuscan town of Massa Marittima. And beneath one of its arches resides the phallic façade.

Based on in-mural lore, the mystical dick-tree was the happenin' spot in town, with various folk gathered beneath it like coworkers around the water cooler. And technically, they are at the water cooler. One frescoed with 25 arboreal genitalia because that's how old-school Tuscans liked their waterworks. (13th-century Massa Marittima residents would be shocked by this century’s lack of imagination regarding penis graffiti on civic structures.)

But dongs were less vulgar and more symbolic in the olden days. So the image isn't just funny, it's historical and educational. One theory says the tree simply represents fertility and good fortune. Booooring.

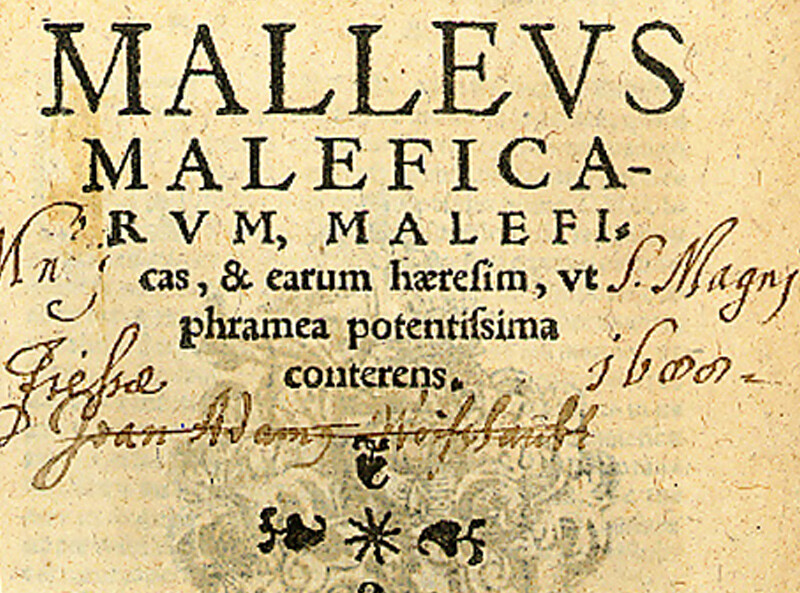

Another posits that this is possibly the oldest image of European witchcraft, revealing some interesting thaumaturgy. It may depict something later detailed in a Latin "witchfinder's guide" called Malleus Maleficarum, which sounds hella rad and doesn't disappoint in translation: "Hammer of the Witches." It helped conscientious 15th-century Christians detect and expose sorceresses for the purpose of getting rid of them.

Therefore, the women standing below the tree and fighting for a fresh phallus aren't the protagonists of an Usher song. But pythonesses carrying out a deviltrous bewitchment: stealing a man's organ and keeping it in a bird's nest, where it would gain sentience and multiply. Pick-up lines were a lot more direct back then, we guess.

An equally slick theory posits that the scene is political propaganda. Around this time, the Guelphs and Ghibellines were political Bloods and Crips allied to the Pope or Holy Roman emperor, respectively, just like modern street gangs. It's possible the Ghibellines created the fresco, then when the prudish, Pope-allied Guelphs took over, they added one significant feature:

An eagle representing the Ghibellines, to imply that the opposing faction is full of sodomizers who'd bring witchcraft along with sexual, spiritual, and societal ruin to the town. Politics has evolved much less than art over the past near-millennium.

Van Gogh's Café Terrace At Night May Be A Last Supper Shout-Out

Vincent van Gogh moved to sunny, wind-whipped Arles in February 1888 to escape the soul-stifling craziness and pretension of big-city Paris. He hoped to establish an artist's commune in the cheery south of France and get into all sorts of Brady Bunchesque familial shenanigans. Sadly, none joined, except (for a couple of months) Gauguin, who was antsy and eager to fulfill his destiny as an age-ravaged foreign pedophile in Tahiti.

Van Gogh only spent about a year in the bright, Mistral-besieged Provencal city but produced many of his most famous paintings here despite, or perhaps due to, his subsistence on coffee and absinthe.

Vincent van Gogh

Among his most gawked at is the Café Terrace at Night, as it's known today. It was Van Gogh's first nighttime thing, painted in September 1888. Actually, since he painted it on the spot and true to life, as researchers dated the configuration of the stars to September 16 or 17th.

Vincent van Gogh

Some say it's a symbolic Last Supper, featuring 12 apostles breaking bread and French wine, which the maître d' probably spit in. One figure lurks in shadow, the traitorous Judas. The central figure is Jesus ensconced in a robe, with the light above serving as a halo and the window behind forming a cross.

Other details may also suggest Biblicality, such as the addition of evergreen boughs on the right, a symbol (appropriated from the pagans) of everlasting life. Why do you think you decorate a tree every December? For fun? Nope, ancient propaganda.

Vincent van Gogh

Also circa late-September '88, Vincent wrote to his brother, Theo, that he felt a "tremendous need for, shall I say the word—for religion." And was apparently already thinking in apostolic terms of 12, while buying 12 chairs for his no-show painting buddies.

That "tremendous need for … religion" quote is from a letter that continues, "… so I go outside at night to paint the stars, and I always dream a painting like that, with a group of lively figures of the pals." Van Gogh longed for companionship, especially at this jeopardous juncture in his life—his psychotic or epileptic episodes and hospitalization were only a few months off, and his death less than a couple of years.

So maybe it's less about Christ and more about wishing he had some boys to crack open cold ones with? Either way, it’s a slapper.

The famed eatery still exists and is now Le Café Van Gogh, a tourist trap piss-nest with a 2.8 rating on Google reviews and worse elsewhere. Here's the address in case you personally want to experience art history while enjoying a $7 mineral water and the worst paella of your life.

Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV of the Ottoman Empire Is An Epic Old-Timey Diss

The term Zaporozhian Cossacks refers to a bunch of surly, burly, fighty former peasants from Ukraine. And Zaporozhian means "beyond the rapids," signifying their domain past the rapids of the Dnipro River. Wow, what a cool historical nominal practice that probably wouldn't sound impressive today—"John across from the rendering plant" or "Sally from beyond the burned-out PetSmart" don't quite hold up.

The other word, cossack, derives from Turkic for "free man" and was bestowed upon serfs (and eventually townsfolk and even a few nobles) who would strike out to the steppes and become, in modern terms, "their own men." Better than toiling on a farm 22 hours a day just to starve, as per European practice throughout the Middle Ages.

These rascally bastards formed a formidable military and political body circa mid-16th to the late-18th century, with a 30,000-square-mile autonomous territory. Here they assumed the role of irascible wiener dog and squabbled with every contemporary group, including Tatars, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Crimea, and Russia.

The cossacks also inspired awesome art. Especially the Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV of the Ottoman Empire:

It measures 6'7'', the perfect height for a three-point-chucking shooting guard with subpar handles. It was painted by Ilya Repin over 11 years and became then the most expensive Russian painting ever when Alexander III bought it for 35,000 rubles. It depicts the supposed drafting of a letter the cossacks penned in reply to Sultan Mehmed IV.

The supposed setting: after the Zaporozhian Cossacks gave the sultan's forces a bit of an ass-paddling, Mehmed IV sent a rudely worded missive asking for the Z’s to surrender, which isn’t how war works. The response from the mercenaries was one of the greatest fulminating remonstrations in history, real or imagined, utilizing an assortment of archaic insults that probably deserve a comeback.

Though with road rage incidents at an all-time high, we don't advise yelling these out your window next time someone cuts you off. Unless it's a Tesla.

Bichitr Exemplifies Mughal Art, Throws Shade At Western Kings

The 17th-century artist Bichitr is so exquisite it's a shame that most of the seven people who have heard of him call him "Bih-s**tter." He was the finest of Mughal court painters, serving as official immortalizer for two prominent emperors, Jahāngīr and his successor-to-the-throne son, Shah Jahān of Taj Mahal fame.

Bichitr studied European art and mended the hemispheric styles. It's why he included realistic details like shadows and seemingly out-of-place putti, those diabetic little Italian angels with the creepy pug-dog-faces. The art is of the "Mughal miniature" style, as per Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings (1615-1618), which packs lots of stuff into a 7-by-9-inch frame. It portrays Jahāngīr, a master of "imperial self-congratulation," being great while throwing shade at everybody not named himself.

Compared to the grand European canvases of battered Jesuses and poop-stained saints modeled on street urchins (which we'll get to soon), Bichitr's compositions are a Juicy Fruit commercial. Floral borders and delicate calligraphy combine with silver and gold metallic paints to attack your eyes with pleasure.

In the painting, Jahāngīr sits on an hourglass and transcends earthly, mortal time. The dudes on the left are in order of propagandic hierarchy. Up top is the Sufi Shaikh, a hot-shot holy man of the Sufi Islamic mystic faith. Lesser than his holiness is the Ottoman Sultan, and lesser still is a hangdog King James I, depicted in a lowly position with a mighty impotent air. His posture is limp, and his expression as resigned and listless as a brachycephalic luxury cat accepting mortality when dinner is a minute late.

At the bottom is a self-portrait of Bichitr himself, holding a painting of also himself, in which he's being honored with royal gifts for being such a great king-painter.

Bichitr was also an expert at portraying hands, an undervalued part of sycophantic portraiture. Even the most mentally deranged of Old Masters sometimes produced a wonky hand or wayward finger. But not Bichitr, who faithfully captured Jahāngīr's hands being blinged-out like a Soundcloud could rapper about to hit mainstream.

Caravaggio's Seven Works Of Mercy Is A Counter-Reformationist Easter Egg Hunt

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio is unjustly the Michelangelo of lesser renown. He's named after the town where he spent his childhood, like your homeboy Fat Cleveland. Yet, instead of being known for guzzling tallboys (though he was for that too), MMdC earned his appellation through unbridled artistic excellence and mad-hat bat-shittery. Hell, he'd be the Michelangelo had he been born a bit earlier.

The "father of the Baroque" led a lifestyle fit for a reprobate-virtuoso. He'd complete a painting in a couple of weeks or less, then spend months walking the streets of Rome with his sword, frequenting taverns, brawling, and banging courtesans. Once, he assaulted a waiter who brought him undercooked artichokes. Though to be fair, Italians don't tolerate artichoke-oriented tomfoolery. Then he killed a guy, though again in Caravaggio's defense, he was only trying to castrate him. So he fled to Naples and became that historic city's exceptional artist, as he had previously been in Rome.

In Naples in 1606-1607, he painted the Seven Acts of Mercy for the altar of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, his first masterpiece after catching a body:

Caravaggio blessed the "Pious Mount of Mercy" church with a gem of Caravaggian (Caravaggiastic? Caravaggelous?) proportions, featuring his specialty play of shade and light, called chiaroscuro. Seriously, it's imbued with unfathomably brilliant, sacred light.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

It displays the Madonna, Child, and Seven Acts of Mercy, as per Matthew 25:35-36, which are apparently good things Christians do out of unconditional love for their fellows. And also to avoid an eternity of roasting in hell-fire. These seven acts of Christian goodness encompass burying the dead, clothing the naked, helping the sick, refreshing the thirsty, and sheltering the homeless. The last couple is a twofer: visiting the imprisoned and feeding the hungry, represented via Roman Charity, the tale of Pero giving suck (historical suck aka breastfeeding, not modern succ) to her father Cimon, who was sentenced to starve.

And that's the beauty of Caravaggio. Ask him to paint you some religion and you don't know whether you're getting a Mary modeled on a bloated corpse, some daughter-father suck, or stabbed in the testicles with a sword.

Thumbnail: Vincent van Gogh