Narf! Meet the Real-Life Inspirations for Pinky and the Brain

The oft-told origin story for Pinky and the Brain goes as follows: While working on the beloved series Tiny Toon Adventures (a precursor to Animaniacs), animator Bruce Timm saw fellow animators Tom Minton and Eddie Fitzgerald in their shared office and drew caricatures of them. Then, Tiny Toons and later Animaniacs showrunner Tom Ruegger drew mouse ears on them.

Thus, Pinky and the Brain were born.

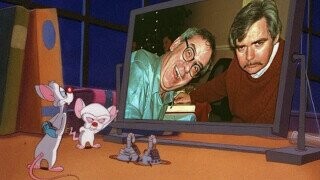

But that’s not exactly true. I recently spoke with Minton and Fitzgerald over Zoom to get the real story, but I certainly didn’t need any convincing of their influence on the lab mice characters.

Don't Miss

Minton, who inspired Brain, talks in a low monotone and his dry wit is accompanied by an ever-stonefaced expression. Meanwhile, Fitzgerald is a joyous ball of energy, often laughing through his gapped teeth. Now both retired and decades older than they were when they inspired the iconic animated mice, the resemblance is still uncanny, even if, as they wish to clarify, some legends have fallen a little far from the truth.

I know you’ve worked together on a number of different cartoons. When was the first time you worked together?

Tom Minton: Filmation, 1978. Though I may have met Eddie at the Hanna-Barbera training program the year before.

Eddie Fitzgerald: Oh no kidding! Yeah, that’s possible.

Minton: Shortly after that training program, we all got laid off by Hanna-Barbera when they sent all their animation-assistant work to Taiwan. I got hired at Filmation, then Filmation Producer Don Christiansen decided to start the first young storyboard department — young meaning under the age of 70. Eddie and I were in that young storyboard department. Everyone there was young except for Paul Fennell.

Fitzgerald: The guy who punched me in the nose!

Minton: Yeah, he was quite a character.

Fitzgerald: I got hazed! They put me in a room with this older guy who was a distinguished animator in his day, but he was really temperamental and I got on his wrong side one day and he punched me in the nose really hard.

Minton: Eddie loved the Looney Tunes director Bob Clampett, and he mentioned Bob Clampett one too many times.

Fitzgerald: Paul hated Bob Clampett.

Tell me about working on Tiny Toon Adventures.

Minton: At that point, I was a writer. I came over there in February 1989, and Warner Bros. was just starting to assemble what was going to be Warner Bros. Animation. A little while later, Eddie was brought on as a director. It’s funny, back then, the word on the street was that we were going to bring back Warner Bros. Animation, and some of the old guys said, “No, that’s not possible,” but we did it.

Thanks to Steven Spielberg getting involved, the money came back to animation. For example, Warner’s wanted to do the music cheaply. They wanted to have a music library like Hanna-Barbera does, where you score like 20 minutes of music, and you have film editors put the same music in every episode like Scooby-Doo. But Steven said, “Oh no. You put my name on something, you hire a full orchestra and you score every bit of it.” He made them do that. That was wonderful. This was the beginning of a revival in animation that was driven by the success of Roger Rabbit.

So, the legend goes that Bruce Timm saw you guys together, drew caricatures of you, then Tom Ruegger drew mice ears on you and that became Pinky and the Brain. Is that right?

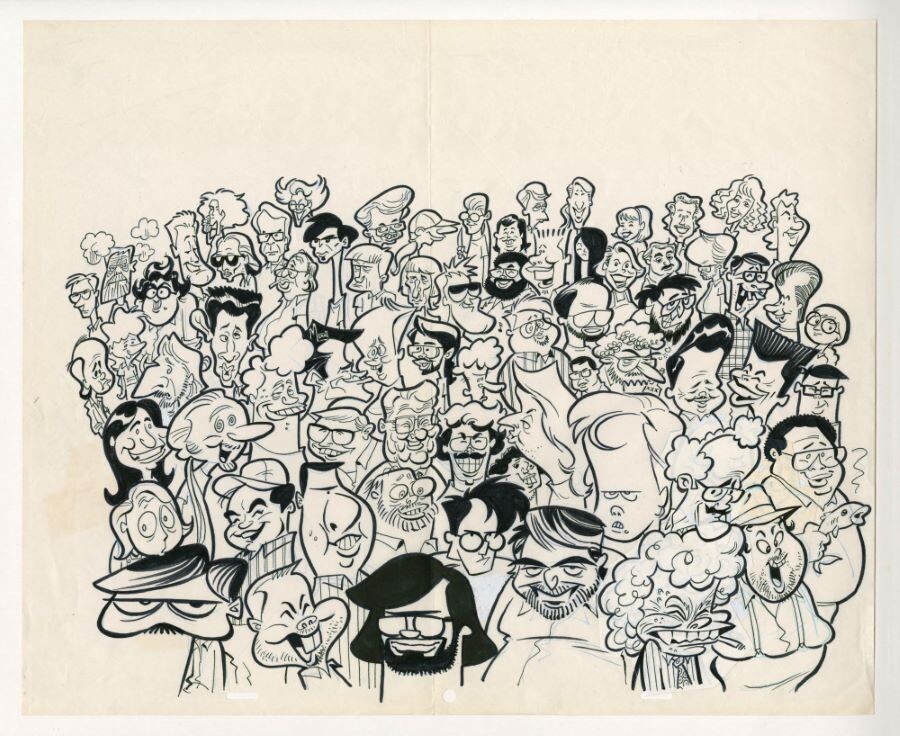

Minton: I don’t think that’s really correct. There was a drawing that Bruce did back in 1990 of the entire crew of Tiny Toons. That’s one of the inspirations they used. I know they also used other artists in the studio. The guy who did the final models on Animaniacs was Ken Boyer. Lynne Naylor told me that Tom Ruegger gave her a picture of me, a photograph, and said, “I want you to do a caricature of this guy as a mouse.”

Fitzgerald: I was one of the progenitors of the drawing of you! Just as a joke, I drew you with sort of a Betty Boop-shaped head, which you don’t have, but I was just fooling around and I put a straight line for your eyebrow ridge and a serious look on your face. It was just meant to be a joke. I didn’t know anything would come of it.

I remember drawing it because Tom was the funniest guy I ever met, yet he had this deadpan expression, which made the funny stuff even funnier. I was just emphasizing that, and I guess Bruce or somebody else picked up on that and made it their own.

Minton: Various outlets have said erroneously that Eddie and I were sharing an office and that we were both producers at Warner Bros., and that’s how they got the idea to put us in there. The only time Eddie and I ever shared an office in our lives was in 1978 at Filmation when we were both storyboard artists. That’s when Tom Ruegger first saw us. He was getting his start as a writer there.

I was at Warner Bros. for Tiny Toons, but I left in 1990. I had to go to Disney. While I was gone, unbeknownst to me, they were developing Animaniacs and basing two characters on Eddie and I. No one ever told me that until I was in a recording session at Disney’s with Maurice LaMarche. He said, “Hey, you know they’re doing you at Warner Bros.? They’re basing a character on you over there, and I’m doing the voice.” I said, “Really? I didn’t know that. Nobody ever told me.”

I said nothing, and let it happen. There was a long tradition in animation of basing characters on people who worked there. Mr. Magoo was based, unofficially, on Leo Salkin, a storyboard artist. He looked just like Magoo, but he always said it was a coincidence. Friz Freleng was the basis for Yosemite Sam, unofficially.

I went back to Warner Bros. in 1992 as a story editor and a writer, but at that point, they had 30 episodes of Animaniacs in the can, though I did end up writing seven episodes with Pinky and the Brain, three of which were in the spin-off series. When I got back to Warner’s, Ruegger said to me, “We’re doing this thing based on you.” I said, “Yeah, I know. It’s okay.”

The funny thing was, in 2006, they released volume two of the Animaniacs DVD, and they interviewed all the writers, including Tom Ruegger. Tom gave them a two-hour interview, and he said, “Yeah, we based Pinky on Eddie Fitzgerald and Brain on Tom Minton.” He goes home that night. He gets a call from the head attorney at Warner Bros., and they say, “Come in tomorrow and redo that interview. This time, don’t say that.”

So, what does that tell you? Nobody ever asked. I mean, I don’t care, but I think it’s amusing that high-powered attorneys lose sleep over this.

So, Bruce Timm’s drawing you’re referencing has almost 100 faces on it, and you two aren’t together or anything. How did they pick you two to base these characters on?

Minton: I wasn’t there at the time, but the story I heard was: They had to have a story bible sent to Steven Spielberg on a Friday afternoon, and they hadn’t figured out who the personalities were for these two lab mice. And it’s an old trick with writers, if you don’t know what to do for a personality, base it on somebody you know. And they wanted to go for contrast. “Who are the two most contrasting characters we know?” Well, Tom and Eddie. There’s even a rough draft of that bible that mentions our names. So, they didn’t come to those drawings first, they came to the personalities first and then just went with it.

They changed certain things, of course. Eddie and I are about the same height, and I don’t sound like Orson Welles and Eddie doesn’t sound like Ringo Starr or whatever.

Fitzgerald: They tested me for that. They put me in a booth and said, “Here’s a couple of lines and do your laugh.” I didn’t know what it was for, and I’ve never forced a laugh, so I didn’t know what they were talking about. I did my best, but it was terrible.

Minton: Neither of us are voice actors.

Tom, when you wrote for Brain, was there any self-consciousness or discomfort writing for a character based on yourself?

Minton: No, you get away from that. There had been a few good ones done before I got there, and when I wrote for Brain, I wrote for a mix of Orson Welles and Vincent Price. My first one was “Opportunity Knocks,” which is still one of my favorites. “Brainstem” is another one that I’m proud of. It was set to “Camptown Races,” and Brain sings all the parts of the brain. Funny enough, that short became a teaching device in medical schools. A resident who went to Columbia University told me that.

Eddie, what was it like storyboarding or directing something with Pinky?

Fitzgerald: I only worked a little bit on the Pinky and the Brain spin-off, and I wrote a couple of shorts for the characters on Animaniacs, but I don’t actually know if they made it into production. I thought it was a pretty interesting concept for a show, so I just went along with what was there.

I didn’t think of Pinky as if it was me, exactly. I was just anxious to get to know the character and to look for animation opportunities. I always think animation is about moving a funny character in a funny way. I saw my goal in the industry as a whole to do stuff that kids could talk about at the playground the next day. I just died for that.

What are your thoughts on the voice actors who played the characters: Maurice LaMarche for the Brain and Rob Paulsen for Pinky?

Fitzgerald: Rob was great.

Minton: Maurice is a great guy. He’s an amazingly talented voice artist. What he did was great. It’s hard to do a character that’s based on another character, like Orson Welles or something, and still have it be interesting and get beyond the impression. He does that.

Were there any other traits of yours that were used for the characters?

Minton: The only thing they stole from me in terms of dialogue is “Yes!” I’d say “yes” like that. With Eddie, they also brought in “narf” and “egad.”

Eddie, please explain where “Narf!” came from.

Fitzgerald: Well, “egad” and “gadzooks” are 17th-century Shakespearean kinds of things. I just like that kind of over-the-top baroque dialogue. As for “narf,” I used to say “narf” all the time at home because I wanted to be sure I never cursed in front of the kids. Like, I stubbed my knee on a coffee table — you want to put out every word in the book, but instead I’d say “Narf!” because there was a kid in the room. I used to say that all the time, but I never thought to use it for animation, and it never occurred to me that anyone else would use it for anything.