The Cracked Guide To The Grateful Dead, Part 3: The Dead Hit The Road

This week on Cracked, we'll be taking a look at the history of The Grateful Dead, or the band who kidnapped Lindsey at the end of Freaks and Geeks. Check out our first and second parts here.

When I began this series, I said I would explain the dancing bears. In July 1973, the Owsley “Bear” Stanley, who had been taping shows (as had other archivists, officially and unofficially), put together an album of tracks he really dug that emphasized the band’s love of roots music. It was also something of a tribute to Pigpen, who was in bad shape, and died before the record was released. The album was called History of the Grateful Dead: Volume One (Bear’s Choice), indicating that there would be more from the archives to come. (Check Spotify to see just how true this is.)

Don't Miss

It’s a great album, with a classic, hard-rockin’ “Hard to Handle” from Pigpen …

… and also some great acoustic tunes from Jerry and Bobby.

But on the back of the album, there was some artwork. Those dancing bears. Owsley and artist Bob Thomas, who would later design the Dead’s other logo, the “Steal Your Face” red-white-and-blue skull with the lightning bolt, found a printmaking slug of a bear, and they thought it would be funny to stamp it on there in red, green, orange, blue, and yellow. Side-by-side the bears look like they are dancing, but Owsley later insisted “they were doing a high step,” not that I’m sure what the distinction is. (I remember hearing lore that Bobby once looked out on the crowd during a trip and said “hey, man, they all look like dancing bears” but this appears to have been made up.)

The point is that it stuck with the fans, and Owsley took to it, too, which means it later got incorporated into the blotter art of his (and other people’s) acid that one could find when the Grateful Dead rolled into town. It would also appear on traded cassettes (and reel-to-reel tapes) of Dead shows, which is another important chapter to this story.

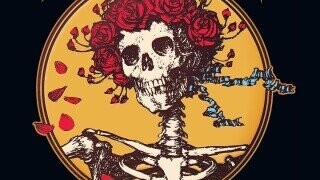

In October 1971, the Dead released an untitled double-live LP. Grateful Dead featured a weirdo skeleton with roses on the cover and was nicknamed Skull F---.

Inside the gatefold (double LPs would open like a book, if you have never held one in your hand) was a note: “Dead Freaks Unite.”

It continued, “Who are you? Where are you? How are you?

Send us your name and address and we'll keep you informed.

Dead Heads, P.O. Box 1065, San Rafael, California 94901.”

In no way did the Dead invent fan clubs – my mother was part of one for Bobby Rydell in the 1950s – but by 1971 the band (and the business mechanisms behind it) recognized that something was happening with this particularly enthusiastic following. The “Dead Heads” who seemed to have no jobs and just followed the band from town to town were gaining a reputation.

How did they survive? Well, shows were cheaper in those days, but the parking lot scene (later renamed—and still named—Shakedown Street, after a later, funky Dead tune) became an unexpected haven of free market enterprise.

While the Dead emerged from the San Fransisco of free love and pinko anti-war sentiment, it must be stated that the band itself never had a problem with making a buck. Gen Z types with a hammer-and-sickle in their Twitter avatars might consider this a disconnect, but the Dead’s brand of anti-authoritarianism has always leaned a bit Libertarian. I’ve already mentioned Robert Hunter, Jerry Garcia’s lyricist. Bob Weir had his own songwriting partner, John Perry Barlow, who later became an Internet pioneer (anyone heard of “The WELL”?) and co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a fund and lobbying group that works in good faith to defend digital civil rights. If you take it at face value, it is righteous. It’s also exactly the type of thing Elon Musk talks about when he says Twitter should be a haven for “free speech.” This is just one example of the counterculture-to-cyberculture pipeline, which does include a heavy techbro element. (The first kindlings of Burning Man is found here.)

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s get back to “the lot” and the Dead Heads who needed just enough dough to fill up their tanks and make the next show. A less-involved fan just coming to a concert could buy a veggie burrito or grilled cheese sandwich off a guy, or some jewelry, or some acid meant to look like Owsley’s. They could also buy some stickers or cheaply made T-shirts (possibly with a dancing bear!) that made it clear that you dug the Dead. (You know who got his start selling art on the lot? Keith Haring.) Did the band care? The band did not care. They were just setting up the scene, and letting the happening happen, man.

More importantly was the tape-trading. Bootleg recordings had long existed among enthusiastic fans (ask Bob Dylan, hell, ask Charlie Parker) but it really went into overdrive with the Grateful Dead. Every show was different! New song order, new arrangements (they played it slower this time!), new 23-minute guitar jams. Some of these were tapes that leaked directly from the soundboards (thank you, Bear; thank you, Betty Cantor) others were from tapers in the crowd that would grow to have their own following.

Every one of these traded tapes was money out of the band’s pocket, right? Well, no. It was free advertising. When you heard how great that “China/Rider” sounded at Winterland, it meant you had to go see them next time they were in town.

While the Dead never officially encouraged tape-trading, they made little effort to curtail it. This is a philosophy shared by many successful jam bands, and groups like Phish from the 1990s or newcomers like Billy Strings and Goose have ridden this wave to great financial success ever since (even if you’ve never heard one of their songs on the radio.)

Meanwhile the 1970s marched on. The Dead toured constantly, and when they weren’t playing together, there were solo projects. Jerry Garcia found himself splitting in multiple directions: he was a key instigator with New Riders of the Purple Sage (an Outlaw Country band), a founder of Old & In The Way (a hardcore bluegrass band, whose repertoire included a sensational cover of the Rolling Stones’s “Wild Horses” as if the U.K. rockers transported to West Virginia), and a funky blues band called the Legion of Mary with African American hammond organ player Merl Saunders at his side. Check out this version of 22-minute version of Jimmy Cliff’s “The Harder They Come” if you’ve got some time to groove. (Of course you've got time! After all, this article only contains...holy crap, 74 minutes of music?)

Jerry eventually formed The Jerry Garcia Band, which for a long time featured Ron Tutt – Elvis’s drummer! – on the skins. He also was speaking less and less from the stage, which only heightened his pedestal for fans who now considered every utterance – every sprinkle within a guitar lick – to hold some kind of important, Messianic message. His plump figure, ratty clothes and Santa-esque beard were, as they say, quite a lewk.

By the mid-1970s, however, the music scene was changing. There was prog rock coming out of Britain (think Genesis and Yes) and there was jazz fusion in the U.S. (think Return to Forever and what Jeff Beck was laying down on Blow By Blow and Wired). This meant an appreciation of longer songs, and who could go longer than the Dead, man? The time had come to show they couldn’t just jam, but could compose, and this meant tracks like “Weather Report Suite,” the entire second side of Terrapin Station and, my favorite, the medley known by fans as “Help>Slip>Frank” off the funkiest quasi-prog psychedelic record of the era Blues for Allah.

Here’s their old pal Bill Graham introducing a live version. Crank this, it absolutely rips.

To the chagrin of some fans who just didn’t understand what is best in life, the Dead began to lean into funk as the decade continued. “Disco Dead,” as it is sometimes called, included the aforementioned song “Shakedown Street” and a fundamental rework of some of their earlier tracks. A great example of this was the change in their cover of “Dancing In The Streets,” originally done in their Pigpen-ish “rave-up” style, now transformed into a monster for dancing fools. If you ever wondered why the Dead needed two drummers, he’s an object lesson in that. This period was absolute fire, but it was about to change.

You can find the rest of Cracked's essay series on the Dead here:

Top image: Rhino Records