Is Robin A Necessary Part Of Batman, Or A Waste Of Space?

For over 80 years, Batman has evolved and changed while still being one of the biggest forces in pop culture. This week, Cracked is doing a deep dive into the Dark Knight.

We're giving away four pieces of art from legendary Batman creatives Alex Ross and Frank Miller courtesy of our friends at The Haul. Enter your email below for a chance to win and learn more here.

Don't Miss

Robin is, quite probably, the most maligned and most beloved of all comic book characters simultaneously. Debuting in 1940, a single year after the brooding of Batman, the teenager in the pixie boots has been a mainstay of DC Comics for nearly a century, both as part of the Dynamic Duo and as a superhero in their own right. And for pretty much that entire time, readers have been wondering one thing: does Robin suck?

It's a conundrum, to be sure. The character is instantly recognizable, no matter who's actually wearing the domino mask, but they're as likely to be a punchline as punch a bad guy. Robin is the quintessential sidekick, as essential as they are extraneous and expendable. Fans and creators alike refuse to take Robin seriously, but, let's be honest, it's hard to imagine Batman without them.

The Hatching of a Sidekick

DC Comics

When Bill Finger, Jerry Robinson, and Bob Kane decided to debut a pint-sized Batperson in Detective Comics #38, they did so for the noblest of reasons: cold-blooded marketing and because they needed a new narrative device. Dick Grayson's Robin – and with him the entire concept of superhero sidekicks – was created as a way to kill two birds with one underaged, underpants-wearing stone.

Sales of Detective Comics at the time were fine, but, as per that meme from the stone ages of 2020, things could be better. So, first and foremost, Robin was thunk up as a way to get the youth of the 1940s away from their newfangled radio programs and stickball games and back to curbside newsstands where they belonged.

Kane, especially, felt that, for some reason, kids who had just barely survived the Depression weren't quite identifying with a dark, brooding millionaire processing his violent trauma through more violent trauma. Throwing a preteen in short shorts into the mix might get the kids' attention, though. Robinson agreed, calling it a "brilliant idea" with "enormous story potential."

DC Comics

Putting a child's life in danger significantly upped the stakes for the Bat. Stories were no longer only about his problems and well-being, but someone else's, too. Overnight, Batman went from an unhinged vigilante to a slightly more cuddly and paternal protector, with Robin acting not only as a surrogate for random victims of crime but for the audience, too.

Finger, meanwhile, was just excited Batman had someone to talk to now. As he put it, "it got a little tiresome always having him thinking." Robin gave the world's greatest detective someone to explain things to in a more organic way. If Bruce Wayne was Sherlock Holmes, then Dick Grayson was his Watson.

DC Comics

The sidekick wasn't just a metaphorical boost, either – he quite literally brightened up the pages. From a purely visual stance, Robin balanced out the darkness of the Dark Knight. As much as Batman was Zorro and other old, shadowy pulp heroes, Robin borrowed from the swashbuckling Robin Hood, both the Douglas Fairbanks version and the early 1900s' illustrations of N.C. Wyeth.

Put all of that together, and it's no surprise the gambit worked. Sales of Detective Comics doubled almost immediately – and so, too, did mixed opinions about the sidekick.

Robin Laid an Egg

DC Comics

The divisiveness of Robin began where the character did, right there in the DC Comics offices. Writer Bill Finger loved the Boy Wonder, but Bob Kane quickly grew to hate him. He missed the "solitary and sinister" version of Batman.

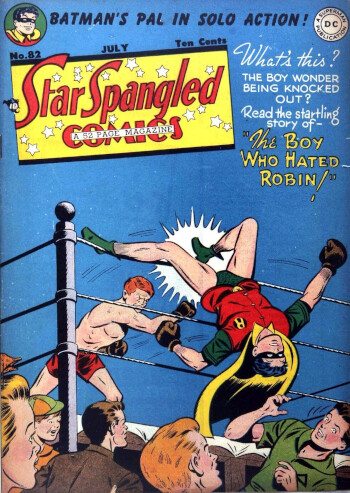

Kane wasn't alone in thinking that, either. For every reader buoying Robin to his own solo stories in Star-Spangled Comics – a run that means Robin actually surpasses Batman in number of Golden Age appearances – there was another reader who thought Robin was just the pits.

DC Comics

Of course, hating on Robin is, as NPR's resident comic book nerd Glen Weldon once wrote, cyclical. It is a constant of comicdom and beyond. The Teen Titans animated series made Robin a leader as cool as Batman; Teen Titans GO!, from the same creative team, roasts Dick at every opportunity. Zack Snyder and Christopher Nolan both went out of their way to say they'd never put Robin in their movies – but both directors snuck him in there anyway.

When Burt Ward (arguably the most famous Robin) slipped into the tights in the 1966 Batman TV show, some fans disliked his hamminess so much they petitioned DC to do the exact opposite in the pages of Detective Comics. It worked: the 1970s found Batman working solo again, harkening back to his pulp roots, while the '80s turned him even grim and grittier.

This, conveniently, brings us to Jason Todd. Todd's Robin was so disliked that readers voted to have him violently murdered by a psychopath. (The margin, though, wasn't quite as wide as you might think; even the objectively worst Robin still had his fans.)

Of course, 20 years later, he came back anyway – because (punching) time heals all wounds, even crowbar fractures and being exploded. But also because Robin is, more than anything, actually about Batman.

Dick & Jason & Tim & Stephanie & Damian

DC Comics

A large part of the reason Jason Todd was hated – other than the fact that it's very easy to hate Jasons and Todds – sorry, Jasons and Todds – is that he was too mean and angry. He was a walking representation of Batman's failure. Which is 100% the opposite of what a Robin should be.

Over the last 80+ years, Batman has officially played surrogate papa to five different traumatized teenagers: Dick Grayson, Jason Todd, Tim Drake, Stephanie Brown, and Damian Wayne. Following in the footsteps of the O.G. Robin, they generally arrive in trouble and then, thanks to Bruce Wayne's fortune, aloofness, and criminal disregard for child welfare get turned into superheroes. Then, almost to a one, they go on to bigger and better things, but only after graduating from the mantle of Robin – or, y'know, dying – and taking on a new name.

There are obviously exceptions here: Stephanie started her career as Spoiler; Damian is Bruce's actual kid; Tim was trauma-free until later; Dick jumped ship to the Teen Titans as Robin. But from a bird's eye view, it's all the same general mold.

DC Comics

The name and character of Robin is inextricably linked to Batman – because Robin only exists as an extension of our headlining caped crusader. Robin is a device to make Batman do something or feel something; they're a reflection of how good or bad Bats is doing at any given moment. Once a Robin becomes their own person, their own hero – once they stop serving Bruce's story – they're outta there.

Because, ultimately, the primary purpose of a Robin is validating Batman. Even within the DC universe, people know that a rich dude dressing up as a bat and breaking criminals' teeth because his parents' died over half a century ago isn't exactly well-adjusted. Sure, he helps, kind of, but it's not hard to believe that Commissioner Gordon would much rather Bruce Wayne got some therapy and maybe used his billions to pay for various social services and better security at Arkham Asylum instead.

DC Comics

Robin, though, not only condones Bruce's fetish gear and violence but makes what Batman does worthwhile. They understand him and confirm that what he's doing, and how he's doing it, really is for the betterment of Gotham – and the betterment of Bruce Wayne, too.

Dick Grayson is, like Bruce, orphaned by murder. But Dick doesn't turn into Batman; he turns into something better. Nightwing is likable and knows how to have long-term relationships; he's inspired by Superman almost as much as Batman; he actually talks to people. Dick isn't always one bad day away from becoming a supervillain. Neither is Tim Drake. Even Damian Wayne and Stephanie Brown are both sanded down from outright evil into something more aboveboard.

Robin is Bruce Wayne in a world where Batman existed to help Bruce Wayne not become Batman in the first place. OK, that sounds like the Riddler wrote that, so let's try again: Robin is a genuine hero, unburdened by trauma and revenge and all of Bruce's darker impulses. If Batman can save Robin, if he can keep Dick and Tim and the rest from turning into him, then he's done his job. Robin is proof that Batman makes the world better.

Pretty much every facet of Robin is a counterpoint to Batman. They are, essentially, the Dark Knight at his brightest and most, uh, morning-y? The opposite of a knight-y? While Robin Hood was the original impetus for the character, the songbird has become the more prevalent association – and robins are traditionally symbols of hope and optimism.

Batman may be vengeance, he might be the night, but Robin is the breaking dawn.

The Dynamic Duo (of Codependence)

DC Comics

To be clear, an underage carny in neon hotpants makes absolutely no sense running around with a noir-inspired detective who works pretty much exclusively in dark alleys and abandoned funhouses. But, put simply, Batman can't exist without Robin.

The best Robins aren't sidekicks but partners – someone who understands that Batman needs help, too.

Let's look at the "A Lonely Place of Dying" arc as an example. After Jason Todd's death, Batman goes to a bad place and starts taking that rage out on bad guys – and on himself. He's reckless and self-destructive and letting himself get beat up to the point that even Alfred, the guy who singlehandedly supported Batman in his myopic quest to become a revenge-fueled opera villain, is all like, "Oh, dear. Master might have a problem."

Only once Tim Drake shows up in a red-and-green leotard is Bruce pulled back from the edge, returning from violent vigilante to actual hero again.

DC Comics

All of which is to say, without Robin, Batman gets dark. Without someone to quip away his worst impulses, without something nobler to strive for, someone else's redemption and protection to set his sights on, Batman loses even a hint of the light.

Warner Bros.

Batman, fundamentally, can't change. But Robin can. And that lets the reader believe, at least for a little while, that maybe we're wrong. That maybe Batman can change, too.

The only thing that sucks about Robin is how enmeshed the identity is with another hero. Good or bad, they're forever trapped in the shadow of that Bat.

Eirik Gumeny (@egumeny) is the author of the Exponential Apocalypse series, a five-book saga of slacker superheroes, fart jokes, and assorted B-movie monsters. Or, if you’re more into classical literature, he added werewolves and assassins to The Great Gatsby, too.

Top Image: DC Comics